Guidelines for decision-making in English pronunciation and listening instruction

Introduction

Deciding what to work on and what to put aside can be notoriously difficult for foreign language teachers, and this seems especially true for English pronunciation work. Here I argue that, in order to make the best use of limited contact hours with learners, a key distinction needs to be made between work focusing on pronunciation and work focusing on listening. If we want them to become as effective as possible beyond the classroom, then we need to prepare them to interact in two roles: as speakers and as listeners. In the words of Celce-Murcia et al:

... our goal … is to help our learners understand fast, messy, authentic speech, ... [which is] much more varied and unpredictable than what they need … to be intelligible ... the goals for mastery are different. (2010, 370)

If the goal is intelligibility — instead of nativelike pronunciation — what do teachers need to take into account when prioritizing in their teaching? Drawing on research and my own teaching experience, I suggest some guidelines for making decisions about teaching pronunciation and listening for a variety of adult learners. This requires an overview of principles and guidelines which have helped me to improve my own decision-making in relation to teaching pronunciation and listening in different contexts. These changes have made it easier for me to exploit listening as an approach to the complexity of English phonology.

1. Factors and prioritising

Designing pronunciation instruction requires teachers to consider situational factors as well as language-specific factors.

Situational factors include institutional requirements, e.g., exams or certifications, textbooks. Sometimes teachers have to teach to a specific exam format or to cover a certain set of book chapters. A language teaching situation more broadly includes the ideas a society has about how languages are (best) learnt and taught. In their book, Grant and Brinton (2014) use second language research to debunk 7 myths about L2 pronunciation:

- Once you have been speaking a second language for years, it’s too late to change your pronunciation.

- Pronunciation instruction is not appropriate for beginning-level learners.

- Pronunciation teaching has to establish in the minds of language learners a set of distinct consonant and vowel sounds.

- Intonation is hard to teach.

- Students would make better progress in pronunciation if they just practiced more.

- Accent reduction and pronunciation instruction are the same thing.

- Teacher training programs provide adequate preparation in how to teach pronunciation.

Most of these myths circulate widely in France and thus influence, to varying degrees, the decision-making of individual language teachers there.

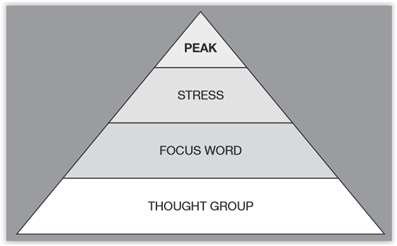

In terms of language-specific factors, my learners seem to appreciate being made aware that an organised system exists for spoken English. Figure 1 shows Gilbert's (2008) Prosody Pyramid, which reassuringly affirms that all is not chaos:

Learners of many types – 1st year science students, MA students of psychology, future or current English teachers - have appreciated using this as a framing device for their own learning, or for designing lesson plans and teaching sequences. Usually I have only a handful of two-hour sessions with them. In that time, we work through exercises for each level, and I explicitly display the pyramid as we address each level.

Among the many language-specific factors, priorities need to be set as efficiently as possible because teaching time is limited. The concept of Functional Load (FL) was originally defined as “a measure of the work which two phonemes (or a distinctive feature) do in keeping utterances apart’’ (King, 1967, 831). FL can help to indicate which vowels to work on in the ‘peak’ of Gilbert’s Prosody Pyramid. Brown (1988, 604) proposed a rank ordering of phonemes for Received Pronunciation (Table 1), with 10 representing maximal importance and 1 minimal importance. He described it as “a tool to identify a set of relatively crucial segmental features for successful understanding in L2 communication”:

| Vowels | Consonants | ||

| 10 |

/e æ/ /æ ʌ/ /æ ɒ/ /ʌ ɒ/ /ɔː əʊ/ |

10 |

/p b/ /p f/ /m n/ /n l/ /l r/ |

| 9 |

/e ɪ/ |

9 |

/f h/ |

| Vowels | Consonants | ||

|

/e eɪ/ /ɑː aɪ/ /ɜː əʊ/ |

/t d/ /k g/ |

||

| ... | ... | ... | ... |

| 1 |

/ɔː ɔɪ/ /uː ʊə/ |

1 |

/f θ/ /ʤ j/ |

Brown’s predictions were not empirically tested until 2006 (Munro & Derwing), who explored the usefulness of FL with regard to Cantonese-speaking learners of English. It was tested again by Suzukida and Saito in 2019, with Japanese learners of English, but I have not yet seen it systematically tested for French learners.

The concept of FL is a good first step when prioritising phonemes, especially when combined with a solid contrastive analysis (e.g., Swan & Smith, 2010), but it has shortcomings. First of all, there is the issue of teachability. To cite Munro and Derwing (2011, 137), “the mere fact that a phonological structure poses difficulty for a learner says nothing about whether it is actually worth teaching or whether it can even be taught”. The flip side of that is learnability: should we assume that learners are able to notice a feature? And then, that they can consciously work on it and make progress? For example, the distinction between /ɔ:/ and /əʊ/ is stubbornly difficult for my native-speaking French learners of English both to perceive and to produce. Yet, with an FL rating of 10/10, it cannot be neglected. A third limitation relates to the abilities and attitudes of listeners, i.e., how comfortably they can process varied pronunciations and how tolerant they are of them. In 1988 Brown noted that stigmatisation exists even in native accents:

… the /ð d/ conflation is found, if only sporadically, in the Republic of Ireland, although it is heavily stigmatized. We may conclude that listeners are accustomed to making the perceptual adjustment necessary for intelligibility of these conflations, but not for the others. (1988, 598)

It is, therefore, not just a question of whether a feature can be taught or learnt, but also how it will be perceived.

2. Personal experience

Moving from trying to “teach everything” to prioritising was a long process for me. When I started teaching French university students to prepare for the CAPES d’anglais, I was unaware of the Functional Load principle. I was told to cover everything that was “different” or “difficult” and I did my best to do so: from individual sounds to compounds, rhythm and intonation, and covering detailed rules and articulatory descriptions. I relied on minimal pairs, lists of isolated words, target sounds embedded in sentences and extended texts to be read aloud. I was a lab monitor for hundreds of lab sessions at all levels, and taught phonetics and phonology – as well as pronunciation – at all levels. Greven’s exhaustive book (1972) was the one I was told to use.

Over time, reduced contact hours forced me to prioritise: exhaustive treatment could no longer be the default objective. First I started to select from Greven’s book those units which (in my experience) were most difficult for my English majors. I also relied on Swan and Smith’s (2010) contrastive analysis of what French speakers had trouble producing. It bothered me that little was mentioned about perception, and no supporting research was cited, no criteria applied other than difference or difficulty. However, I did not have the time or the skills to test the claims being made, because I was caught in the immediacy of my teaching situation.

When Hancock’s English Pronunciation in Use books first came out in the early 2000s, the appendices were a revelation: Guides for speakers of specific language, Advice on units to leave out, and Sound pairs it would probably be useful to work on. The section on English as a Lingua Franca (ELF) was a novelty, as it went beyond contrastive analysis and set priorities for specific contexts. This was the first place I saw a concrete, pedagogical application of ELF. On one page, Hancock (2012, 164) presented a table with a modified list inspired by Jenkins’ seminal ELF work (2000). Each unit’s title was listed in a colour indicating three degrees of importance for ELF: very important (red: units 1-6,8-16, 18-24, 37-44), may be important (green: 27-36), or not important (black: 7, 17, 25, 26, 45). This intrigued me, as Unit 17 covered the two dental fricatives /θ ð/ and Unit 45 rising and falling tones. How could these features not be part of a language lab syllabus?

To prepare readers for the concept of ELF, Hancock urged them to think about how they use English (Hancock, 2012,163):

This clearly highlights interactional considerations and, thus, the needs of listeners – in a pronunciation workbook. The book devotes 15 units (Units 46-60) to “features for listening, not features you are expected to pronounce yourself” (Hancock, 2012, 164). This was the first time that I saw not only a socially-motivated, contextualised distinction being made between work on pronunciation or listening, but also concrete materials to help me act on that in the classroom.

3. Underlying principles and key notions

The next section explores how a few underlying principles and key notions can orient our pedagogical choices, even when we are not aware of their influence.

In 2005 Levis proposed that two principles underlie pronunciation teaching and that the goals of each are distinct. In teaching that is motivated by the Nativeness Principle, the goal is to get learners to sound nativelike. In contrast, when the Intelligibility Principle orients teaching, the goal is to help learners to be understood. Both Principles should be seen as listener-sensitive as well as context-dependent. For the first, in the case of my students preparing to take the CAPES or Agrégation, the jury’s requirements need to be respected; nativelike pronunciation is valued and therefore, must be the objective of the speaker. Passing such an exam is not, however, the explicit goal of the vast majority of my university students, let alone most secondary or primary school pupils, for whom mastering an ‘English R’ may not be essential to their intelligibility. Nonetheless, they may still express a desire to sound nativelike, or at least to ‘pass’ as not being a learner.

In language instruction based on the Intelligibility Principle, the goal is for potential or imagined listeners to understand when a learner speaks. One way I have tried to act on this is by focusing on what I refer to as “gifts” which make learners’ speech more easily understandable. For example, university students may imagine themselves working one day in multicultural and/or multilingual work contexts. Figure 2 is an illustration of how something as seemingly straightforward as pronouncing one’s name can become a brief teaching point, as well as a “gift” for listeners:

The first item (my first name) is said with rising intonation, then I pause, before saying the next item (last name) with falling intonation to signal the end. Packaging the information in this way respects the listener, making it easier for them to hear and correctly identify the two units of information: the first package is my first name and the second is my last name. For example, many French students introduce themselves last name first, so that an anglophone listener may use the student’s last name, yet believe they are using their first name (e.g., Simon Thibaud). Another example is when my science students cannot pronounce the words hypothesis, mountain or important, in a way that is recognisable to me. I tend to assume that other listeners will have trouble too, and I advise my students either to use a synonym which they can pronounce smoothly (but there are no synonyms for hypothesis …), or to use a strategy to help their listeners e.g., point at a written version the first time the word is said.

Both principles highlight the obvious fact that speaking is done in interaction with a listener. Research has shown that listeners are sensitive to different aspects of speech. At this stage it is important to address a trilogy of interrelated notions commonly used in such research (accentedness, comprehensibility and intelligibility) and how they are related to features of spoken English (Table 2):

|

Intelligibility (INT) |

Accentedness (ACC) |

Comprehensibility (COM) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Definition | accuracy of understanding | subjective perception of difference to nativelike pronunciation | subjective perception of processing ease |

| Key language features | phonemic divergences | phonetic divergences, phonemic divergences | phonemic divergences; fluency, vocabulary & grammar |

| How measured | transcription, questions (e.g., True-False, multiple choice, etc.) | usually Likert scales | usually Likert scales; potentially response latency data |

Intelligibility can be seen as a measure of actual understanding, and it is usually measured by a written task, such as dictation or responding to multiple choice questions. The other two notions are perceptions; accentedness is a perception of difference, of “linguistic nativelikeness”, and comprehensibility is a measure of how easy or difficult a listener finds it to understand a speaker. These two are usually measured with Likert scales, e.g., On a scale of 1-5, rate how easy it was to understand Speaker A. 1 = extremely easy, 5= extremely difficult. All are influenced by phonemic divergences, but accentedness is based primarily on phonetic distinctions. Comprehensibility is the most multi-dimensional measure and involves fluency, grammar and vocabulary:

… phonemic divergences in L2 speech influence accent, intelligibility and comprehensibility, while phonetic divergences only affect accent ratings, a finding later replicated by Zielinski (2008) and by Trofimovich and Isaacs (2012). Given the stated goal of improving intelligibility rather than accent, instruction should not focus on the mispronunciation of sounds that are ultimately still recognized as a member of the target category. (Thomson, 2018, 22)

It is thus possible to make an argument for a listener-based curriculum, if the goal is listeners to “still recognize” sounds as members of the target category, instead of speakers trying to sound nativelike. This requires listeners – and speakers – to accept variation. Hancock tried to promote this in the EPU books:

As a model for you to copy when speaking, we have used only one accent, from the South of England. But when you are listening to people speaking English, you will hear a variety of accents, both native & non-native, in some parts of the listening material. … one section deals specifically with different accents. (Hancock, 2012; my italics)

Many of my students found the idea of variation hard to accept and could not see the point in learning to actively listen not only to a variety of native accents, but also to diverse non-native accents. It struck me that this reaction was based on a view of accented speech as less prestigious.

4. Status of accented speech

The status of accented speech is another example of how situational factors necessarily influence curriculum design. The definition of accent used here is Moyer’s (2013, AA): “a set of dynamic segmental and suprasegmental habits that convey linguistic meaning along with social and situation affiliation”. Beyond the semantic meaning of the words people choose, their accent is a highly salient marker of their identity and reveals their status as a group member (in-group or out-group). In other words, from a listener’s perspective, accent can also be defined as the degree to which the acoustic features of someone’s speech are perceived as Other. These features have an impact on how listeners perceive speakers (i.e., the messenger) and what they say (i.e., the message). For example, if an uncontested fact is pronounced by two voices, the one with a stronger accent is less likely to be evaluated as true.

French-accented L2 English is what many of our learners produce. They have ideas about what language teaching and learning should involve, and the degree to which they have succeeded or failed to “learn” English, e.g., Mais j’ai toujours été nul en anglais or L’anglais est vraiment trop dur, je ne vais jamais y arriver. Such common remarks – which I regularly hear in France but never heard when teaching in Germany or Poland – reveal that for my learners here in France, English is perceived as valued by society – or at least, it is seen as omnipresent and therefore inescapable. My learners also often say that they will never manage “to be perfect”; they have an Ideal Self (Rogers, 1959) in mind and somehow feel inadequate compared to it, e.g., I should be able to speak perfectly/know all the vocabulary or rules, …. Such representations and the pressure they generate must be kept in mind, especially if teachers choose to no longer target nativelike pronunciation.

The status which people accord to accented speech is often revealed when pronunciation is worked on. Table 3 broadly summarises how three different groups of learners with whom I have worked tend to have different motivating principles and levels of confidence in relation to their pronunciation of English:

| English majors (LLCER Anglais, MEEF) | ESP students (LANSAD) & teachers teaching in English (DNL, EMI) | Non-academic professionals | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Motivating principle |

|

|

|

| Level of confidence |

All relate their accent to how listeners will perceive their level of competence. The English majors often want to “pass” or be mistaken for native users of English. DNL teachers in secondary schools or English-Medium Instruction teachers at university want to be perceived as competent in their field and worthy of respect, regardless of how their English sounds. In short, those operating in an academic context are more likely to lack confidence. I have found that professionals working outside academia (the 3rd column) tend to be the most pragmatic and are relatively free of complexes when it comes to speaking. The issue of identity seems to colour pronunciation work, and this is not the case when working on vocabulary or grammar, e.g., I have never heard a learner say, If only I could master the present perfect, people would be impressed by my English. Perhaps this is because learners sense that paradoxically, it is listeners who determine a speaker's identity – but they do not know how to react to that realisation.

These different groups of English users have different representations of how they should sound, and these representations reflect the two underlying principles posited by Levis (2005). He argued that a paradigm shift was needed, beyond the choice of target model(s). Language teachers guided by the Nativeness Principle typically ask which nativelike accent they should help learners aim for and perhaps achieve. In contrast, teachers guided by the Intelligibility Principle ask how they can help their learners to be understood by others. The necessary associated question is – understood by whom and in which contexts?

If we assume that we – and our learners - will encounter and use English in a variety of contexts, then we need to keep in mind what Hancock calls the Variability Principle in his 2019 article, ELF: Beyond dogma and denial:

“if it exists in a widely understood variant of English, then it’s probably ok”.“TH is pronounced as F in some widely understood accents of English, so it’s ‘probably not a big problem if my student pronounces it that way’”.

This is helpful but does not go far enough, because although /θ/ pronounced as /f/ may be understood in English-speaking countries, it may be a feature of child speech or otherwise socially stigmatised. Nativelike pronunciation is not always synonymous with acceptable. Another example is a German student I once worked with in the early 1990s. He had spent a wonderful year in Glasgow as a teaching assistant, training and playing rugby with a local team. He came back with a perfect Glaswegian accent and inserted the “F-word” into almost every sentence. This is the perfect example of how the mere fact that a feature exists and is used in a native accent does not necessarily mean the native feature is appropriate to the learner’s context or acceptable to their listeners. In the case of this German student, on returning to Germany he had to work very hard to modify his speech – lexis and pronunciation – before the competitive national exams to become a highschool English teacher there. It is a not-uncommon illustration of how intelligibility cannot be our sole criteria for teaching something:

While we have rightly idealized intelligibility and to a lesser extent comprehensibility as the goals of instruction, we must also accept that we cannot control the reactions of all listeners, and that for some L2 English learners, in some contexts, a demand for acceptability may trump our idealized standards. (Thomson, 2018, 26).

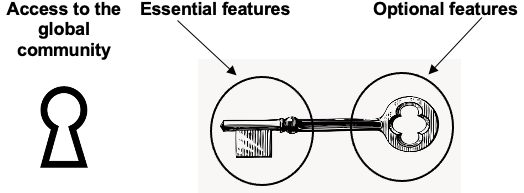

The acceptability of a given pronunciation feature is bluntly defined by Szpyra-Kozlowska as “the degree of annoyance (irritation) it triggers in (listeners)” (2015, 76). To continue with the example of the German student: in the early 1990s, the Bavarian exam jury would most likely have unfavourably evaluated a marked Glaswegian accent in a native German speaker, as only two native accents were acceptable at that time, a General American English or Standard Southern British accent. Hancock argues that if speakers want access to the global community, it is not enough to be intelligible or easily comprehensible, their speech must also be acceptable. He illustrated this with the metaphor of a key (Figure 3):

In Essential pronunciation features Hancock includes the distinction between vowels, and the importance of stress, both lexical and phrasal. In contrast, Optional features are those usually chosen by the speaker to make physical articulation easier for themselves, e.g., reductions; such features do not tend to be chosen by speakers in order to make it easier for listeners to understand them. Acceptability therefore involves choices made by the speaker among both the Essential and Optional features. This metaphor keeps the focus on the speaker, but it is extremely difficult to change how we speak, or to master different accents, styles and registers, especially in another language. Fortunately, it is also possible to train our ears to cope with variation, and in the 21st century this has become much simpler.

5. A real-world example

New technological developments have made it possible to efficiently train our ears in new phonemic inventories, and thus – hopefully – improve not just our ability to process variation in spoken English, but also our tolerance for it. Most notably, High Variability Phonetic Training (HVPT) is “a proven technique about which every language teacher and learner ought to know”, to cite the title of Thomson’s article (2018). HVPT is a computer-based language learning tool which uses systematic exposure to variation, in order to support both cognitive and social objectives. It provides ear training in new phonemic inventories (e.g., Bambara or Brazilian-Portugese accented English), which is useful for three reasons. First, such training improves perception, and this can lead to better production. Second, it is very effective and is much easier to scale-up than speaker training alone. And finally, it also helps to change attitudes, improving tolerance.

Thomson created an on-line version of HVPT (EnglishAccentCoach), but here I’ll describe a Norwegian implementation of HVPT because potentially there are parallels between it and the French context. In Norway, Koreman and his team (2009) at the Norwegian University of Science & Technology developed a Computer-Assisted Listening and Speaking Tutor (CALST).

It is a series of online exercises based on a contrastive analysis of the speech sound inventory of a learner’s self-declared native language and of the target Norwegian dialect. Norwegian lacks an accepted pronunciation standard but there are two written standards, Bokmål and Nynorsk. The CALST database stores the speech sound inventories of four major Norwegian dialects as well as over 500 foreign languages. Learners of Norwegian typically focus on achieving active competence in one standard. However, while learners living in Norway must learn to speak only one variant of Norwegian, in order to become communicatively effective language users in Norwegian society they nonetheless have to be able to understand many different variants. This is because Norwegian language policy encourages speakers to use the pronunciation of their dialect irrespective of the situational context. CALST is institutionally recognised but also has an impact in wider society. As such, it could be an example to all countries with diverse language communities, to help speakers of official languages (and their variants) and other languages to more easily integrate the language community/ties they value.

Koreman’s work in Norway provides real-world evidence that language variation can be managed (and become manageable) in instructed language learning, via tools such as HVPT. In other words, we can learn to accommodate when listening, as has repeatedly been shown in studies (see Thomson, 2018). From a pedagogical perspective, Celce-Murcia et al. made a similar argument in favour of instruction that is designed to help learners cope with variation as listeners and to distinguish listening from speaking goals:

… our goal as teachers of listening is to help our learners understand fast, messy, authentic speech … [which] … is much more varied and unpredictable than what they need to produce in order to be intelligible … (2010, 370)

This brings me to my final point, about how teachers can help learners do more than just “endure” spontaneous speech. In order to understand why such speech is trickier than reading the written word, Cauldwell draws attention to a crucial fact: while reading goes at the reader’s pace (the receiver’s pace), listening goes at the speaker’s pace (the producer’s pace) (2019). It therefore seems sensible for speakers to be encouraged to take into account the needs of their listeners. Likewise, listeners should be given opportunities to cope with what Cauldwell calls the multiple “soundshapes” of spontaneous speech.

6. Two models of speech

Cauldwell worked extensively to raise awareness within the international English Language Teaching (ELT) community that teaching listening requires us to rethink our models of speech ((Many of Cauldwell’s original materials are freely available on his website: https://www.speechinaction.org/.)), and to tackle authenticity in speech. He posited two models of speech, the Careful Speech Model (CSM) and the Spontaneous Speech Model (SSM), for which the main traits are summarised in Table 4:

| Careful Speech Model (CSM) | Spontaneous Speech Model |

|---|---|

| Greenhouse and Garden (ELT classrooms) | Jungle (the real world) |

|

Citation form & sequences of citation forms /səʊ/ /wi:/ /faʊnd/ /aʊt/ |

Multiple soundshapes of forms and sequences /swi:faʊnnaʊʔ/ |

| The language shapes the speech | The speaker shapes the speech |

| Rule-governed, tidy | Unruly, messy, unpredictable |

| Appropriate for pronunciation work | Appropriate for listening work |

The CSM is the realm of the statements, rules and guidelines about the soundshapes of words and sentences, e.g., What is the correct way to pronounce this word or to say this sentence? It is appropriate for pronunciation work because the carefully enunciated citation forms and carefully articulated sentences (e.g., similar to potted plants lined up in a Greenhouse or in a Versailles-style Garden) most distinctly illustrate the laws of phonetics and phonology – including English-specific variables. In contrast, the SSM is more appropriate for listening work because it better prepares learners for a reality they cannot control. The model describes the sound substance of the real world, which Cauldwell refers to as the Jungle, a place which recognises “the wildness, messiness and unruliness of the sound substance of everyday speech – captures it, tames it and makes it teachable and learnable” (2019). In the Jungle the speaker can be much more playful and creative in shaping their speech. Spontaneous speech is where the user-specific variables, or the Optional features of Hancock’s key metaphor, are most obviously encountered. It is also where listeners have to “endure” multiple sound shapes.

Conclusion

We readily accept that examiners (e.g., on the CAPES or Agrégation jury, or on a Cambridge examining board) gain expertise through practice, and that guidelines and training are necessary. That acceptance could also be expanded in language teaching, to include the idea that listener training is as essential as speaker training. Reconsidering the role of the listener forced me to rethink how I teach pronunciation for different learners, in different contexts. Now I know why I devote precious time to one feature but not another, and as often as possible my choices are based on what my learners will probably need to be effective out in the real world, interacting with other speakers and listeners.

The majority of my teaching is currently based on the Intelligibility Principle, because my learners are predominantly students doing a university degree in science and technology. Table 5 provides a priority checklist meant to raise awareness and potentially spur reconceptualization. It is based on my teaching experiences as well as research (mine and others’):

|

In an ideal world English pronunciation teachers would focus on spoken language features that … |

YES | NO | |

|---|---|---|---|

| … are statistically frequent and of high … | |||

|

Does it improve the speaker’s intelligibility? (i.e., Will listeners understand them?) | ||

|

|

||

| … ease communication | |||

| Does it improve the speaker’s comprehensibility? (i.e., Will listeners find it easier to understand them?) | |||

| … are teachable | |||

| … are learnable | |||

| … are research-validated as appropriate for a specific teaching or learning context and/or specific context of future use | |||

The last consideration, which encourages teachers to consult research, might seem too time-consuming to realistically consider – or the research may not yet exist. Nonetheless, taking the time to answer the other questions (e.g., Is Feature X teachable and/or learnable for my learners?) might lead teachers beyond their own classroom experiences and representations, while also respecting their hard-earned expertise.

To conclude, the buzzword “imperfection” has been sprinkled all over social media in the last decade (e.g., Embrace Imperfect Action: Progress, Not Perfection, 12 Reasons Why Imperfect Is Perfect). All the occurrences of the word nod to the same idea – that it is better to make an imperfect attempt than to constantly strive for utter perfection. Similarly, it would be unrealistic to think that the majority of English language teachers could take the time to work through this checklist for each feature that could be included in a lesson or exercise. However, the checklist attempts to condense the essential ideas of this text. The act of considering the questions will hopefully stimulate some constructive re-thinking of why we do what we do, or at least improve our awareness thereof.

Notes

Glossary

Accent. The Oxford English Reference Dictionary defines accent as follows: “a particular mode of pronunciation, esp. one associated with a particular region or group (Liverpool accent; German accent; upper-class accent)”. Accent can also be defined in relation to interaction with other people, as speech that sounds different to one’s own - the individual sounds may be different, especially the vowels, or perhaps intonational patterns differ. Moyer’s definition neatly combines both.

Accent and accent-based discrimination have been explored in a variety of fields, such as applied linguistics, sociology and social psychology. An online database of people’s experiences of such discrimination can be found at The Accentism Project in England (https://accentism.org/).

See: Baratta, Alex. 2018. Accent and teacher identity in Britain: Linguistic favouritism and imposed identities. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

Dovchin, Sender and Dryden, Stephanie. 2022. "Unequal English accents, covert accentism and EAL migrants in Australia", International Journal of the Sociology of Language, volume 2022, n°277, pp.33-46.

Roessel, Janin, Schoel, Christiane and Stahlberg, Dagmar. 2020. "Modern notions of accent-ism: Findings, conceptualizations, and implications for interventions and research on nonnative accents", Journal of Language and Social Psychology, volume 39, n°1, pp.87-111.

Accentedness. The definitions in Table 2 are from two seminal papers by Munro and Derwing in 1995.

See: Munro, Murray J. and Derwing, Tracey M. 1995a. "Processing time, accent, and comprehensibility in the perception of native and foreign-accented speech", Language and Speech, volume 38, n°3, pp.289-306.

Munro, Murray J. and Derwing, Tracey M. 1995b. "Foreign accent, comprehensibility, and intelligibility in the speech of second language learners", Language Learning, volume 45, n°1, pp.73-97.

Accent reduction. Accent reduction refers to the idea that one needs to ‘reduce’ certain features of one’s speech and implies a deficiency-centred view of another person’s way of speaking. A lucrative business has sprung up online with slogans like ‘get the south out of our mouth’ in the USA, where ‘coaches’ promise to help people ‘reduce’ their accent and thus improve their professional prospects. The opposite is what pronunciation teachers often call accent addition, whereby people are taught to extend their repertoire of possible speech features. Far-reaching ethical issues underlie what might appear to be a minor terminological distinction.

See: Thomson, Ron I. and Foote, Jennifer A. 2018. "Pronunciation teaching: Whose ethical domain is it anyways?", in John M. Levis, Charles Nagle and Erin Todey (eds.), Proceedings of the 10th Pronunciation in Second Language Learning and Teaching Conference. Ames: Iowa State University, pp. 226-236.

DNL. DNL is an acronym used in French schools where the letters stand for Discipline non-linguistique. It is used to label teaching of a school subject other than a language (e.g., maths, history or physics) in a foreign language, typically English but also Spanish or German.

EMI. EMI is an acronym used in European higher education to refer to English-medium instruction, i.e., teaching subjects in English. Such a teaching format has spread across Europe since the early 200s, primarily as part of the internationalization of higher education. It raises numerous ideological, political, social and pedagogical issues, many of which have been investigated by academic researchers and policy-makers.

See: Dafouz, Emma. 2018. "English-medium instruction and teacher education programmes in higher education: Ideological forces and imagined identities at work", International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, volume 21, n°5, pp.540-552. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2018.1487926

Molino, Alessandra, Dimova, Slobodanka, Kling, Joyce and Larsen, Sanne. 2022. The evolution of EMI research in European higher education. London: Routledge.

Wilkinson, Robert and Gabriëls, René (eds.). 2021. The Englishization of Higher Education in Europe. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press. https://doi.org/10.5117/9789463727358

'English R'. When my students talk about the ‘English R’, they may be referring to either the post-alveolar approximant of Standard Southern British English (SSBE) or the approximant (retroflex or bunched velar) of General American English (GAE). They might also be implying something about rhoticity or its absence, e.g., the non-rhotic coda /r/ in SSBE. Regardless of their exact meaning and the exact variety of English they have in mind, they notice that the pronunciation of the letter <r> is different to how it is pronounced in French.

LANSAD. LANSAD is an acronym used in French higher education where the letters stand for langues de specialistes d’autres disciplines. It is frequently used to refer to language classes for students specialising in non-linguistic fields, e.g., English classes for students doing degrees in psychology, business or geology. An approximate yet imperfect translation would be English for Specific Purposes (ESP).

See: Van der Yeught, Michel. 2014. "Développer les langues de spécialité dans le secteur LANSAD – Scénarios possibles et parcours recommandé pour contribuer à la professionnalisation des formations", Recherche et Pratiques Pédagogiques En Langues de Spécialité - Cahiers de l APLIUT, volume 33, n°1, pp.12-32. https://doi.org/10.4000/apliut.4153

Likert scales. Likert scales are named after their inventor, Rensis Likert, and are a type of psychometric rating scale commonly used in surveys, e.g., Please rate xxx, on a scale from 1-6;where 1 = strongly agree and 6= strongly disagree. They have been widely used in L2 speech perception studies but not without being contested.

See: Busch, Michael. 1993. "Using Likert Scales in L2 Research. A Researcher Comments", TESOL Quarterly, volume 27, n°4, pp.733-736. https://doi.org/10.2307/3587408

Nativelike. In this article the term means the language a person identifies as the first one they used - and this could refer to any variety of English. Here, nativelike pronunciation refers to speech that sounds like the speaker used this language first in life, e.g., she sounds native, you speak like a native. Psycholinguistic research has shown that the processes involved in learning our first language (L1) are very different to the ones involved for subsequent languages (L2, L3, …), e.g., attentional processes are assigned differently. Thus, the distinction is crucial in the field of second language acquisition, for example.

For more on how the terminology has been problematized, see Davies (2003, 2013) and Dewaele (2018), as it is useful for EFL teachers to be aware of the issue.

See: Davies, Alan. 2013. Native Speakers and Native Users: Loss and Gain. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/native-speakers-and-native-users/D0CE561A99A702C0C8F7882E85DEB4BA

Davies, Alan. 2003. The Native Speaker: Myth and Reality. Multilingual Matters. http://www.multilingual-matters.com/display.asp?K=9781853596223

Dewaele, Jean-Marc. 2017. "Why the Dichotomy ‘L1 Versus LX User’ is Better than ‘Native Versus Non-native Speaker", Applied Linguistics, volume 39, n°2, pp.236-240. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/amw055

Prosody Pyramid. Approaches to prosody analysis differ significantly from author to author. The terminology used by Gilbert is concisely explained in her freely available work Teaching pronunciation using the Prosody Pyramid (2008). She wanted teachers and students to develop “listener friendly” pronunciation (1).

The terms in Figure 1 are defined by her as follows:

Thought group: "how speakers group «words so that they can be more easily processed" (10)

Focus word: "the most important word in the group. It is the word that the speaker wants the listener to notice most, and it is therefore emphasized. To achieve the necessary emphasis on the focus word, English makes particular use of intonation" (12).

Stress: Gilbert explains that vowel length, vowel quality and pitch changes are crucial to a syllable being perceived as stressed (15-19).

Peak: "a syllable that receives the main stress … represents the peak of information in the thought group. It is the most important syllable within the most important word, and, therefore, the sounds in the peak syllable must be heard clearly" (14).

See: Gilbert, Judy. 2008. Teaching Pronunciation: Using the Prosody Pyramid. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. https://www.tesol.org/docs/default-source/new-resource-library/teaching-pronunciation-using-the-prosody-pyramid.pdf?sfvrsn=dedc05dc_0

Response latency data. Response latency data measures how long it takes for a reaction to occur. For example, in an experimental study participants may be asked to click on one button when they see a blue box on the screen, but on a different button when they see a red box. Such data can provide insight into how a person is processing speech. In a speech perception experiment, participants may decode the signal very well and carry out the task (e.g., identify words), but if challenging conditions are induced (e.g., noise, multiple speakers, ambiguous initial phonemes) they take more time to carry out tasks. Response times are typically measured in milliseconds.

See: Baese-Berk, Melissa M., Levi, Susannah V. and Van Engen, Kristin J. 2023. "Intelligibility as a measure of speech perception: Current approaches, challenges, and recommendations", The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, volume 153, n°1, pp.68-76. https://doi.org/10.1121/10.0016806

Role of listeners. The role of listeners has repeatedly been signaled by L2 speech researchers as crucial not just in experimental settings, but also in instructed learning contexts, for example: "Focusing exclusively on the L2 speaker is especially likely to lead to a deficit approach to L2 pronunciation, in which L2 speakers’ pronunciation is compared to (usually monolingual) L1 speaker norms, in some cases even if the ostensible goal is intelligibility rather than accuracy. Language educators cannot have a principled way of assessing intelligibility if they ignore the listener’s role, which may lead to uncritically using a so-called standard variety, typically an L1 variety, as a yardstick by which to measure the learner’s pronunciation. If one instead recognizes that listeners also have an important role to play, learner assimilation to a specific norm is less important, because mutual accommodation allows the interlocutors to communicate even when they do not share the same variety. This does not mean that pronunciation teaching becomes irrelevant, but it does suggest a shift in focus … " (Lindemann & Subtirelu, 2013, 585).

See: Lindemann, Stephanie and Subtirelu, Nicholas. 2013. "Reliably Biased: The Role of Listener Expectation in the Perception of Second Language Speech", Language Learning, volume 63, n°3, pp.567-594. https://doi.org/10.1111/lang.12014

Bibliography

BROWN, Adam. 1988. “Functional Load and the Teaching of Pronunciation”, TESOL Quarterly, volume 22, n°4, pp.593-606. https://doi.org/10.2307/3587258

CAULDWELL, Richard. 2019. “The implications of authenticity for teaching listening”. [Plenary talk], ALOES conference, Université de Lorraine (Metz), May 29-30.

CELCE-MURCIA, Marianne et al. 2010. Teaching pronunciation: A course book and reference guide (2nd edition). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

English Accent Coach, https://www.englishaccentcoach.com

GILBERT, Judy B. 2008. Teaching pronunciation: Using the prosody pyramid. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. https://www.tesol.org/docs/default-source/new-resource-library/teaching-pronunciation-using-the-prosody-pyramid.pdf?sfvrsn=dedc05dc_0

GRANT, Linda and BRINTON, Donna (eds.). 2014. Pronunciation myths: Applying second language research to classroom teaching. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. https://doi.org/10.3998/mpub.4584330

GREVEN, Hubert. 1972. Elements of English phonology. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France.

HANCOCK, Mark. 2019. “ELF: Beyond dogma and denial”, Speak Out! 60. Retrieved from http://hancockmcdonald.com/ideas/elf-beyond-dogma-and-denial

---. 2012. English pronunciation in use (intermediate). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

JENKINS, Jennifer. 2000. The phonology of English as a lingua franca. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

KING, Robert. D. 1967. “Functional load and sound change”, Language, volume 43, n°4, pp.831-852. https://doi.org/10.2307/411969

KOREMAN, Jacques et al. 2009. “Computer-assisted Norwegian Teaching for Foreigners” [PPT talk]. Mutual Information Talks in ISK (MITISK), Institutt for språk og kommunikasjonsstudier NTNU, Trondheim.

LEVIS, John. M. 2005. “Changing contexts and shifting paradigms in pronunciation teaching”, TESOL Quarterly, volume 39, n°3, pp.369-377.

MUNRO, Murray J. and DERWING, Tracey. M. 2011. “The foundations of accent and intelligibility in pronunciation research”, Language Teaching, volume 44, n°3, pp.316-327.

MUNRO, Murray J. and DERWING, Tracey M. 2006. “The functional load principle in ESL pronunciation instruction: An exploratory study”, System, volume 34, n°4, pp.520-531. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2006.09.004

ROGERS, Carl R. 1959. “A theory of therapy, personality and interpersonal relationships as developed in the client-centered framework”, in Sigmund. Koch (ed.), Psychology: a study of a science. Vol. 3: formulations of the person and the social context. New York: McGraw Hill, pp.184-256.

SZPYRA-KOZLOWSKA, Jolanta. 2015. Pronunciation in EFL instruction: A research-based approach. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

Suzukida, Yui and Saito, Kazuya. 2019. “Which segmental features matter for successful L2 comprehensibility? Revisiting and generalizing the pedagogical value of the functional load principle”, Language Teaching Research, volume 25, n°3, pp.431-450. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362168819858246

SWAN, Michael and SMITH, Bernard. 2010. Learner English: A teacher’s guide to interference and other problems. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

THOMSON, Ron I. 2018. “High Variability [Pronunciation] Training (HVPT): A proven technique about which every language teacher and learner ought to know”, Journal of Second Language Pronunciation, volume 4, n°2, pp.208-231. https://doi.org/10.1075/jslp.17038.tho

Pour citer cette ressource :

Alice Henderson, Guidelines for decision-making in English pronunciation and listening instruction, La Clé des Langues [en ligne], Lyon, ENS de LYON/DGESCO (ISSN 2107-7029), décembre 2024. Consulté le 25/02/2026. URL: https://cle.ens-lyon.fr/anglais/langue/guidelines-for-decision-making-in-english-pronunciation-and-listening-instruction

Activer le mode zen

Activer le mode zen