«We’re Going on a Bear Hunt»: Traditional and Counter-traditional Aspects of a Classic Children’s Book

Introduction

The book starts off as an archetypal story of an immemorial kind in which heroes set off in search of a monster as is the case of Saint George, the patron saint of England, a motif used by Anthony Browne in his book Into the Forest (cf. the cross in the little boy’s basket) (Browne, 2004). Unlike dragons, however, bears did exist in Britain until they became extinct, and hunting originally implied a need for food, a need to protect the herds, later turning into a need for sport. Hunting animals down to the point of extinction is congruent with a human desire, or human necessity, depending on one’s views on it, for domination over the natural world, as understood and theorized by a major contributor to the British imagination, Charles Darwin. As to Beowulf, traditionally thought to be the first literary text in Old English, it features a momentous conflict between man and beast. The British Library website describes it as follows: “Written in Old English, it tells of a thrilling struggle between the hero, Beowulf, and a bloodthirsty monster called Grendel" ((http://www.bl.uk/onlinegallery/onlineex/englit/beowulf/index1.html)). But the dragon and the bear are also the enemies within. They represent otherness and monstrosity of a psychological kind.

Originally written in English, illustrated and published in Britain, We’re Going on a Bear Hunt has been among the most widely read, most largely translated and sold, most warmly recommended children’s books in the last three decades.

I would like to show that the book can accommodate various forms of critical appreciation of tradition and counter-tradition. Though it is a read-aloud book primarily designed for very young children, it is a rich pool of material that lends itself to analysis on different levels. Its potential to develop intercultural sensitivity is equally considerable – if we consider the book to convey with it certain forms of perception that differ from one country, one community to the next.

Let us also remind ourselves that children’s books are “an adult practice with intentions towards child readers… […] Children’s literature is not so much what children read as what producers hope children will read. […] The actual purchasers of children’s books always have been, overwhelmingly, not children but parents, teachers, librarians, adults.” (Nodelman, 2008, 4). Regarding the pictures found in a children’s books we must also remember that “…what is meaningful is what the text doesn’t say. A visual detail provided by the pictures makes the text’s apparent simplicity itself the source of great complexity, fraught with a cultural and political import it would not have had if it had simply named what its pictures showed.” (Nodelman, 2008, 11)

The Guardian filmed a conversation between Helen Oxenbury, the illustrator, and Michael Rosen who was responsible for the text to mark the 25th anniversary of the book (The Guardian, 2014). Taking place in the headquarters of Walker Books Ltd. it features the two artists sitting at a table surrounded by copies of the book translated in several languages, an enlarged illustration of the forest scene on the wall, but also a teapot, cups, plates and a large supply of cakes on a china cake stand that create the impression of a fancy tea party. A large illustration by Helen Oxenbury for Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland published by Walker Books in 1999 was placed behind Helen. The visual environment set up for the occasion is rich with literary and cultural connotations: We’re Going on a Bear Hunt is being celebrated as part of a set of iconic British creations and practices. A previous article was published in 2012 in The Guardian about the making of the book. It gives further information about the sequence of events, from text to book. I chose to consider the material from the 2014 video and to look closely at the book to write this paper.

1. From oral performance to text

As he recalls how the book came to be, Michael Rosen remembers saying to the editor that the story “belongs to the folk -- whoever the folk are – it belongs to them…” ((This statement as well as the subsequent statements are extracted from conversation filmed by The Guardian in 2014.)), thus insisting that the origin of the story could not be dated but had a set place in the collective imagination. He and innumerable anonymous others told and retold the rhyme orally before David Lloyd, who was working for Walker Books, particularly liked “that bear hunt thing” and commissioned Michael Rosen to write it down. Following the bardic tradition, Michael Rosen used to perform the poem in schools, and we understand that he went on performing it after the book was published, which certainly fed the reputation of the book over time.

Part of the text for the book is Michael Rosen’s own creation: “Back came a little letter saying ‘it’s not long enough’ and so I had to think of some other scenes. And thus came the forest and the snowstorm…”, which is a telling example of how much influence editors, publishers and the market have on creation. What seemed to have produced a maximum effect in the oral shape (“I really liked that… especially that bear hunt thing…”) needed to form a longer unit to suit the requirements of a written and illustrated work designed to be commercially successful. As we know from the history of literature, printing and publishing, different genres foster different expectations from different audiences in different contexts. Obviously David Lloyd and the editors working on the project knew how to maximize the book’s commercial and literary appeal. The story is said to be “retold” by Michael Rosen on the title page. The word “retold” acknowledges past storytellers as well as Michael Rosen’s additional input. Retellings are a combination of old and new, they are arguably the stuff of literature, but the fact that David Lloyd was instrumental in the transformation from oral performance to written text points to the crucial role played by publishers and editors in the shaping of print culture as increasingly revealed by today’s research. The two extra scenes are, however, Michael Rosen’s own creative response to the publisher’s demand. Not only did he make the story longer, as requested, but he gave it greater momentum as nature becomes more hostile and the atmosphere darkens in the forest and the snowstorm scenes. He also kept to the idea that the characters’ progress was impeded by natural obstacles, first by grass, then by water, then by mud. They stumble and trip on the treacherous wood floor; they plod through the snow.

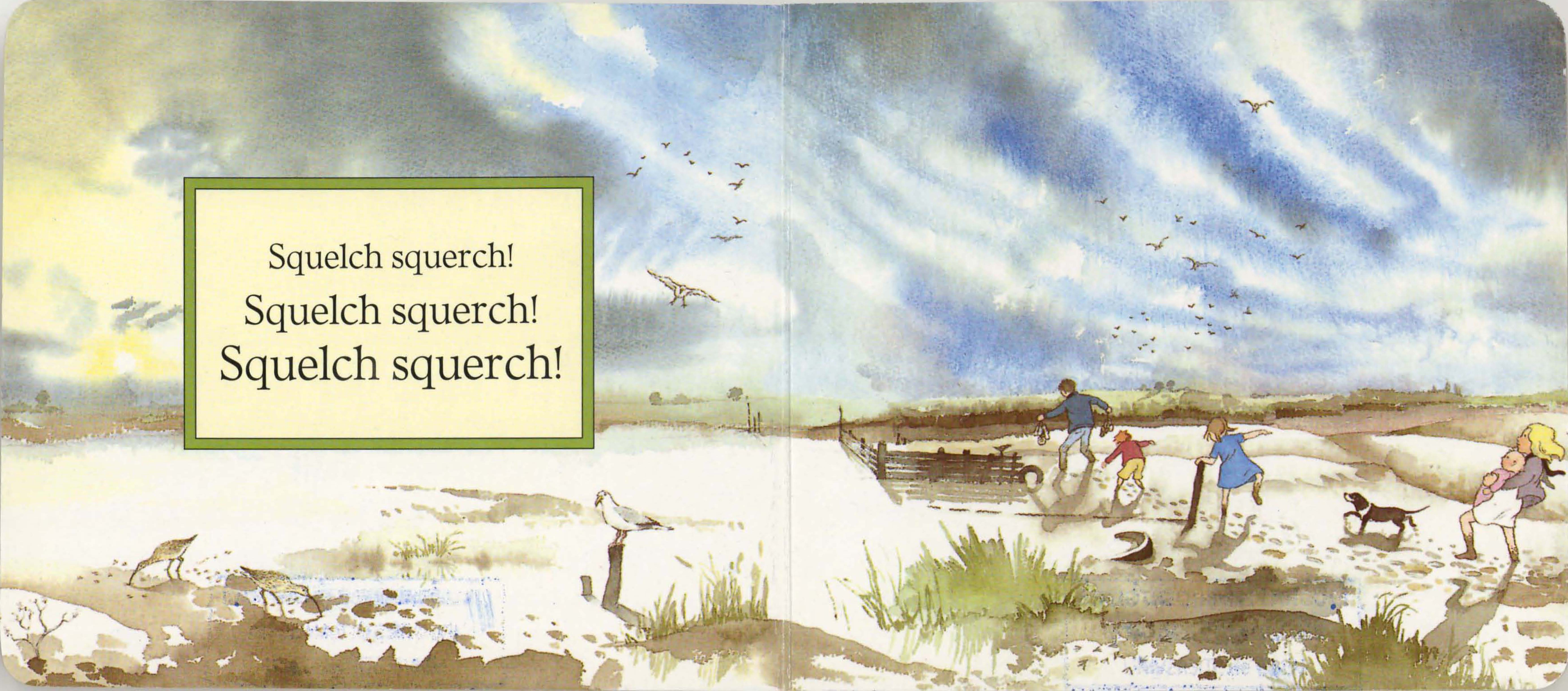

Michael Rosen also explains that he had to find a written equivalent for the noises he made with his voice when performing the rhyme, which he found an onerous task. The regular sequencing of these onomatopoeias and their bold typographical layout on the page are an important part of the book’s identity. Again had it not been for David Lloyd’s intuition that “it might make a book”, Michael Rosen may never have stretched his writer’s talent in that direction.

The book is fun and theatrical. As explained by Wiam El-Tamani:

“Oral storytelling is a medium traditionally responsive to its audience. It derives its vitality from the continuous live exchange between performer and audience which, moment by moment, actively informs, and transforms the performance.

Good picture books are written with this theatrical aspect in mind, making the most of the pacing and the drama of the turning of the page.” (Wiam El-Tamani, 2007, 28)

2. Epic or mock-epic?

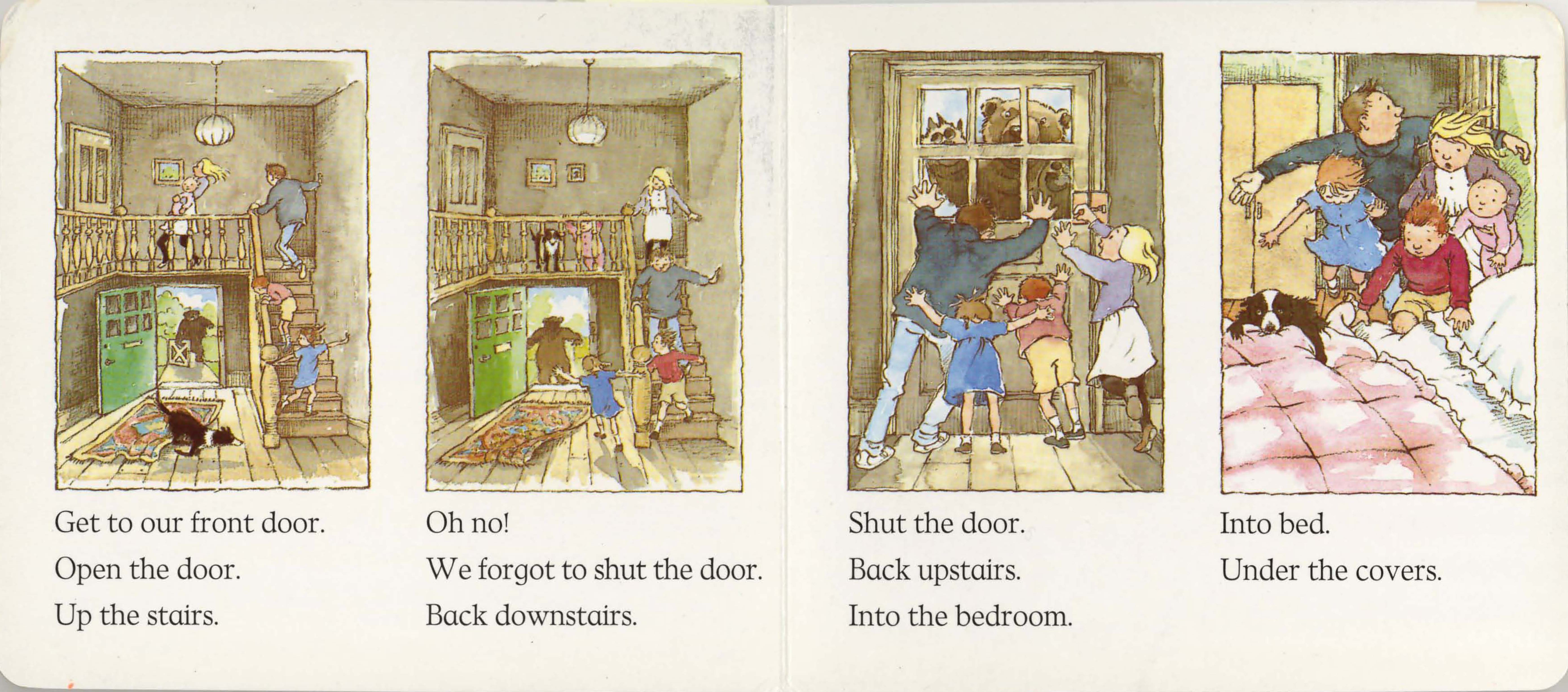

But the unfolding drama is also a parody. As the family retrace their steps in the final pages the epic definitely turns into a mock-epic and the protagonists switch from heroes to frantically fearful human beings. In fact, the chorus “We’re going on a bear hunt. / We’re going to catch a big one. / What a beautiful day! / We’re not scared.” contains enough fraudulent boastfulness for the characters to sound unsure or -- were we to discuss adult literature “unreliable” -- from the start, and increasingly so as the weather deteriorates and the obstacles worsen. The game goes as follows: no obstacle, it seems – but only seems -- will defeat the will of the party to move forward, apart from the monster himself, which is when “epic” unequivocally becomes “mock-epic” and fear, not bravado, becomes the driving force. The pronoun “we” is a convenient screen from the beginning especially coupled with the present tense. “We” speaks of number, of collective strength, it speaks of unity and victory. “We are going…” implies determination and certainty. But “we” is somewhat false as no two individuals can ever think or feel the same at once. Voice and song allow the illusion that it is possible.

The epic tradition demands that heroes, either as a group or on their own, demonstrate extremes of courage and triumph over monstrous enemies. Mock-epic, which came later in the history of literature as a reaction against the inflated ideals of epic, ridicules the heroic premises to replace them with more realistic less codified responses, better suited to new social realities. Then came the invention of childhood and the rise of the unconscious. The following piece about a boy pursued by an imaginary enemy and unable to face it is Charles Dickens’s ebullient version of the un-heroic. The writer had a first-hand knowledge of children’s fears and today’s writers and publishers of children’s stories are astute psychologists. Anthony Browne, to name him again, produces books filled with distress, abuse, loss and parents that will fail their children. Writing for a readership of adults (although the segmenting of readers into age brackets was much less strict than it is today) Dickens combines the vividness of a child’s trauma with that of entertaining drama:

He would not have stopped then, for anything less necessary than breath, it being a spectral sort of race that he ran, and one highly desirable to get to the end of. He had a strong idea that the coffin he had seen was running after him; and, pictured as hopping on behind him, bolt upright, upon its narrow end, always on the point of over-taking him and hopping on at his side—perhaps taking his arm—it was a pursuer to shun. It was an inconsistent and ubiquitous fiend too, for, while it was making the whole night behind him dreadful, he darted out into the roadway to avoid dark alleys, fearful of its coming hopping out of them like a dropsical boy's-Kite without tails and wings. It hid in doorways too, rubbing its horrible shoulders against doors, and drawing them up to its ears, as if it were laughing. It got into shadows on the road, and lay cunningly on its back to trip him up. All this time it was incessantly hopping on behind and gaining on him, so that when the boy got to his own door he had reason for being half dead. And even then it would not leave him, but followed him up-stairs with a bump on every stair, scrambled into bed with him, and bumped down, dead and heavy, on his breast when he fell asleep." (Dickens, 1998, chapter 155)

Transgression (the boy disobeyed his father in order to know where he went at night) resulted in an horrific discovery. The same applies to We’re Going on a Bear Hunt. The terrible confrontation with the bear produces the following conclusion: “We’re not going on a bear hunt again.” Both narratives are cautionary tales, a genre that predates the invention of print. Both narratives make the most of the pacing and the drama involved in oral storytelling.

3. What the pictures say

After Michael Rosen finalised the text, Walker Books commissioned Helen Oxenbury to produce the illustrations. It apparently took several years between the writing of the text and the completion of the book: “A couple of years passed… and I get people who’d come up to me and say ‘I’ve heard that it’s going to be a book and what do you think it’s going to be like?’...” Judging by the length of the book, the publishers gave Helen Oxenbury quite a lot of freedom. She was allowed to exceed the 32-page standard favoured by the industry. The book contains 40 pages of dynamic visual material that serves the text but also departs from it in some meaningful way. The repetitive nature of the rhyme might have been a trap but the artist managed to compromise between the enjoyment of repetition and that of surprise.

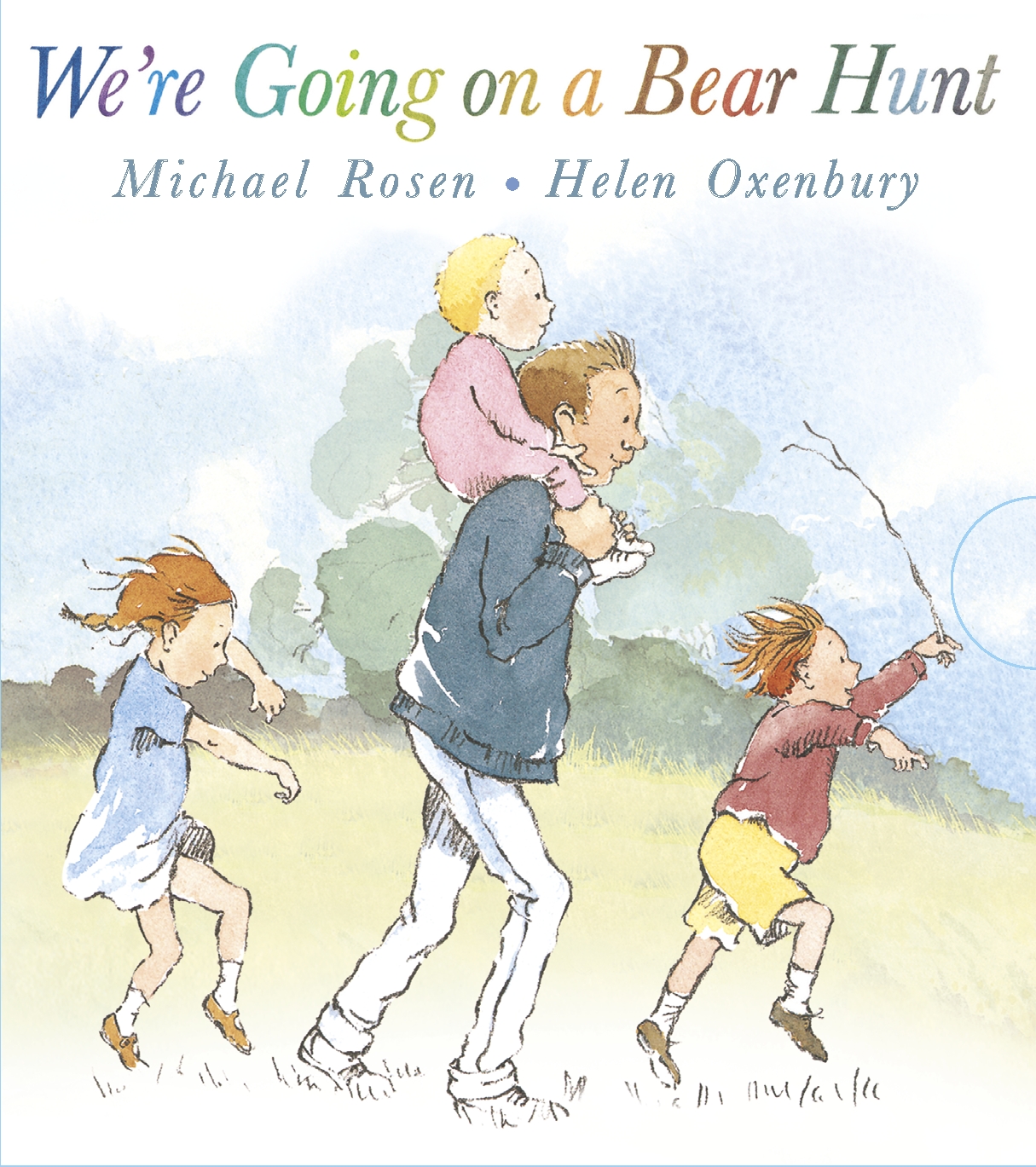

Helen Oxenbury recalls that Michael Rosen had originally thought of “kings and queens and all sort of things going after this bear…” (“I actually have the first written text that you did… with your notes on them… saying the characters that you imagined…”) but she decided to “bring this down to a family” and she thought of using her own family: “It did sort of reflect my family”. Her intention therefore was to modernize Michael Rosen’s initial ideas by making “we” less regal, less medieval, more socially relevant to late 20th century Britain.

She had her children in mind but thinking back she admits that her portrayal of her eldest son was not entirely successful: “I think I actually failed to make him a young teenager… I think he does look more like the dad.”

4. Illustrating gender

What Helen Oxenbury considers as an artistic failure had, in fact, extremely interesting consequences. To most readers the taller male figure on the cover carrying the baby on his shoulders is the father (and a possible reminder of St Christopher which would increase his gravitas). The book therefore seems to represent a single-parent family especially as their adventure ends in a huge bed meant for parents. The comforter quilt that fills the image is fluffy and pink. For whatever reason (Are the parents separated? Is the mother working? Is she doing something on her own as an independent woman?), the father or the figure thought to be the father is in charge of the four children for the day. As a result, because of expectations concerning gender roles and manhood, male heroism is put into pink perspective and the book appears more modern politically than Helen Oxenbury had intended. What is thought to be the adult male looks as panic-stricken as the children in the illustrations. He leads the retreat, carries the baby in several pictures and spreads his arms out protectively as the family reaches the bed, but the escape requires an individual effort from each and all. The threat of death is not deflated by a single-handed action from a man acting as a saviour. Male vulnerability comes across in the illustrations unbeknownst to the illustrator.

The following extract from an earlier era encapsulates the idea of an ideal man-father – viewed as a solitary individual or in competition with other men. The story is told in the past tense by his daughter:

He walked and walked and walked along the shore, looking for the rocks that joined the two islands. He walked all day, and once when he met a fisherman and asked him about Wild Island, the fisherman began to shake and he couldn't talk for a long while. It scared him that much, just thinking about it. Finally he said, "Many people have tried to explore Wild Island, but not one has come back alive. We think they were eaten by the wild animals." This didn't bother my father. He kept walking and slept on the beach again that night. (Ruth Stiles Gannet & Ruth Chrisman Gannet, 1948, 17)

In contrast with this post WWII father who does not feel a spot of bother in any circumstance, Helen Oxenbury’s father figure acknowledges fear and even terror plainly in front of the children. Is the baby in the pink jumpsuit a boy or a girl? In the 2014 video Helen Oxenbury provides the answer but given the colour of the feather eiderdown at the end, a debate might ensue as to the meaning of pink -- whether it can be used as evidence for gender.

Yet when it comes to female gendering in We’re Going on a Bear Hunt, the opposite happens: the illustrations are suggestive of an old-fashioned, nostalgic vision of girlhood. The girls wear frocks and one of them has black tights on as well as bloomers (see her crossing the river) like an Edwardian child. They have long hair while short hair for girls and women were the trend in the 1980’s in Britain. The white socks and leather shoes worn by the younger boy and girl also suggest an earlier historical era post WWII. The father figure, on the other hand, wears jeans with upturned bottoms, a loose jumper and white sneakers, a style in fashion in the 1980’s. Like gender roles, gender display is socially and historically constructed. The older girl’s outfit is not representative of a 1980’s teenager but she is also seen carrying, protecting and looking after the baby in several scenes. Her behaviour contains a strong mothering element, to the extent that some readers may be tempted to consider her as the mother to match the young father figure. In other words, if the father figure points to a counter-traditional family unit the young females’ appearance binds them to tradition. In fact, the older sister bears a definite resemblance to the Alice drawn by Helen Oxenbury for her illustrated version of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1999). Interestingly, however, according to the reviewer for The New York Times, “Helen Oxenbury’s Alice is a pretty little thing in sneakers and a blue jumper right off the rack at the Gap.” (Rebecca Pepper Sinkler, November 21, 1999) Thus a portrayal that seems old-fashioned in one context may seem overly modernized in another one. Helen Oxenbury confessed that the characters in We’re Going on a Bear Hunt “did sort of reflect” her family, but she didn’t give further details as to how much, or how many, of her children went into the illustrations. Regardless of biographical accuracy, it is unlikely that her eldest daughter wore black tights in summer, for summer it must be, at the beginning at least, if the poppies are out.

5. What vision of England?

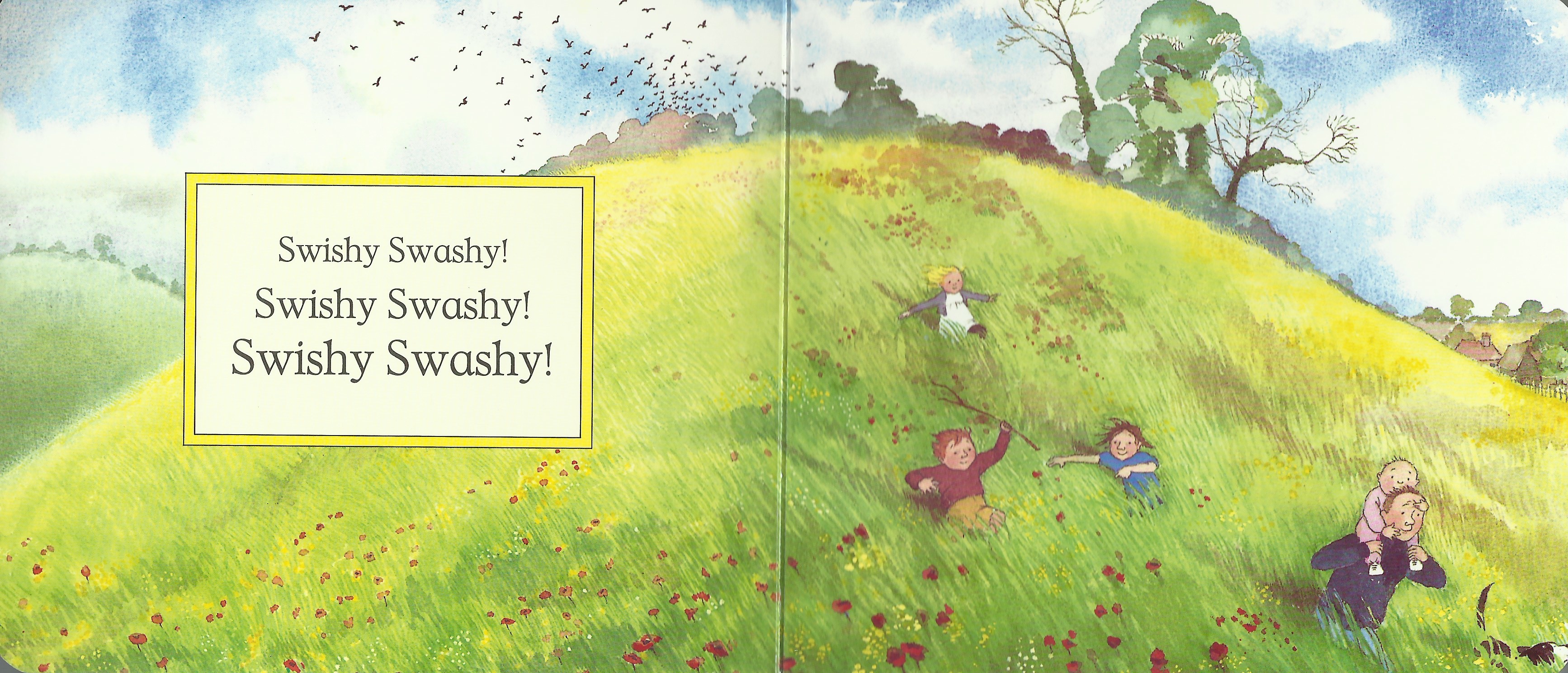

Helen Oxenbury opted for a pastoral vision of the country, starting with the grassy hill with the old farmhouse in the distance as well as the trees, the flock of birds and the mottled sky. Julian Mischi explains:

Helen Oxenbury opted for a pastoral vision of the country, starting with the grassy hill with the old farmhouse in the distance as well as the trees, the flock of birds and the mottled sky. Julian Mischi explains:

The countryside is a central feature in national symbolism and rural images often serve as signs of the Nation. This allegory of the Nation became particularly widespread when Europe’s nation-states were forming. Whether in literary output or ideological accounts of the national community and its origins, the symbols of the Nation and of the countryside are commonly bound together. This is especially true of England where the countryside is traditionally associated with the ‘national identity’. Englishness, which is taken here simply as the set of representations associated with being English, is closely tied in with an imagined rural world. […] And this dual identification of Nation and countryside is captured in the vocabulary as ‘countryside’ contains ‘country’. (Julian Mischi, 2009, 110)

For Roy Strong, the author of Visions of England, the illusion, recognized and understood as such, is nonetheless emotionally spellbinding. He is prepared to add to its magnification and to eulogize at length:

Identity always exists in the imagination and nations, in the scholar Benedict Anderson’s famous phrase, are ‘imagined communities’. But as far as imagined communities go, the rural vision of England strikes me as an attractive one. It is peaceful and tranquil; it speaks of a society that exists in harmony and where life follows the cycle of the seasons; and it respects and preserves the natural environment. It is, in Shakespeare’s immortal words, ‘This other Eden, demi-paradise’. It is a corrective to the speed and greed of urban life and an aspiration to those who are longing to escape the hustle and bustle of our big cities.

That rural idyll is still embraced by the millions who every year visit our National Parks, our country houses and their gardens, and those sections of our countryside that have become iconic, such as the Lake District and Constable’s Suffolk; who take enjoyment from our great landscape art and the novels and poems that celebrate country life; and last but not least, by all those who find pleasure in the allotments and gardens. (Roy Strong, 2011, 205)

Not to mention the weekly BBC television programme Countryfile devoted to “The people, places and stories making news in the British countryside” aired every Sunday evening, or the BBC radio 4 programme On Your Farm which aims at “Getting to the heart of country life with a look at individual farming endeavours.”

When he discovered the illustrations and saw the picture of the family running down the field Michael Rosen was transported away from his own imaginings of who “we” were. He talks of seeing an impressionist painting -- Claude Monet’s Poppy Field because, presumably, of the scattering of poppies, the sloping field and children setting off on a walk. And yet the trees, the architecture of the old farmstead in the nook of the hill and the cloudscape also bring John Constable’s impressions of land and sky to mind. Interestingly Helen Oxenbury used watercolour, like John Constable, and she grew up in Suffolk like John Constable, but beyond this particular live connection, watercolour is a culturally significant medium in the history of art in Britain. It carries with it a sense of artistic legacy and national history which informs, albeit subtly, the meaning of this children’s book.

Most illustrations contain traces of human settlement (as does Monet’s Poppy Field – the big house at the far back with its numerous eyes), whether it is a village in the distance or a cluster of houses (snowstorm), a sailing boat (bear cave), field strips, a winding road, or a wooden structure across the mudflats. What looks like abandoned tyres may be part of a mooring device for boats, or disused fish traps. Helen Oxenbury avoided placing a dwelling in the woods as this would have drawn the reader’s imagination into the realm of witches and fairy tales, but she stood the would-be father on a fallen veteran tree in the attitude of a supervisor, arms akimbo, like a captain or a supervisor.

Overall the vision of England presented by the artist in the book is not one of wild nature devoid of human presence or human activity. Signs point to the hustle and bustle of men and women in the vicinity as the family’s adventure unfolds – like a side narrative speaking of work, warmth, community and safety.

The country represented in the illustrations is the England depicted by other writers and visual artists in very many canonical texts and paintings:

Again, each Sunday afternoon we had a walk still dressed in our best and we could draw in the sweet country air, this island’s attar of roses, coming from the sea overland to where we meandered, the woods all about us, rooks up in the sky, the cattle in the fields. Every lane so it now seems was sunken, tufts of grass and wild flowers overhung our walks and sometimes, coming over the hill, we had that view over all the county where it lay beneath in light haze like a king’s pleasure preserved for idle hours; that was how we went within earshot of the guns, chattering and happy through loveliness. (Henry Green, 1989, 42.)

The beginning of Orlando, a novel that concentrates several centuries of English history, features a similar panoramic view:

He had walked very quickly uphill through ferns and hawthorn bushes, startling deer and wild birds, to a place crowned by a single oak tree. It was very high, so high indeed that nineteen English counties could be seen beneath; and on clear days thirty or perhaps forty, if the weather was very fine. Sometimes one could see the English Channel, wave reiterating upon wave. (Woolf, 1986, 12)

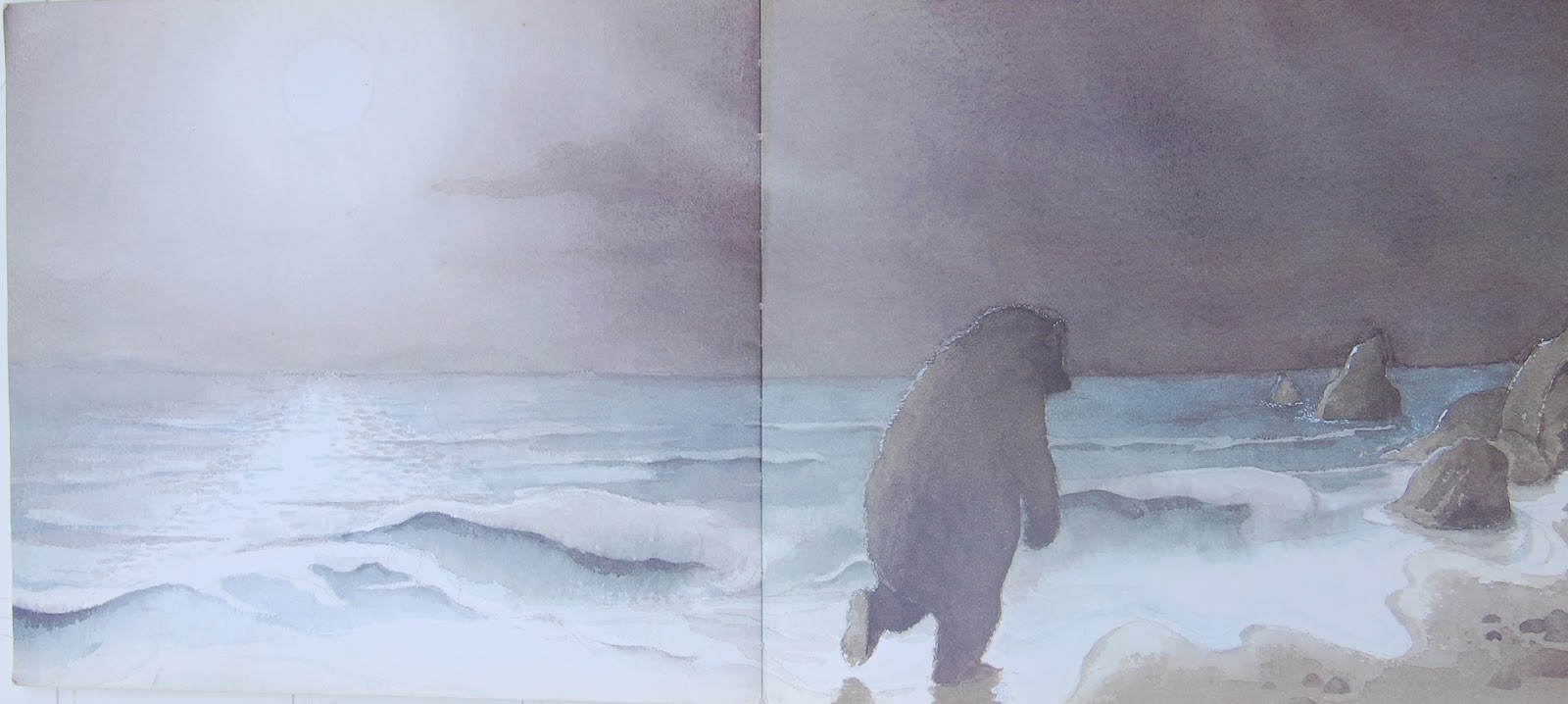

Both writers are inspired by England-Britain as land surrounded by sea. Placing the bear in a cave by the sea as Helen Oxenbury did is an original idea, the expected setting for brown bears being forested or mountainous areas, but it also meant that her characters would journey from the fields to the coastline. Adding a sailing vessel in the distance (see the characters in the cave), very much like in the painting by John Everett Millais, The North-West Passage (1874), is not a neutral decision either. It alludes to Britain’s dedication to sea travel. In fact, the double page that starts the book before the title page is a stretch of coastline at low tide with bare rocks and sand, gulls gyrating in the sky, some settled down to look for food, and three boats in the distance sailing in company. An unusual visual introduction for a bear hunt but one that makes sense if we consider the prolific influence of Britain’s maritime heritage. Appearing on the road and opening the second chapter of Thomas Hardy’s The Return of the Native, after a first chapter entirely devoted to the surface and depth of earth-land-heath is an old former naval officer, still dressed in his boat-cloak, hobbling along the road.

6. An eye on wildlife

We must also consider Helen Oxenbury’s emphasis on birds in the illustrations. Two curlews foraging through the mud and a gull are seen on the mudflats. Curlews are shoreline birds and residents in Britain all year round – a fine example that children’s books are written and illustrated by adults with adult experience with an implied reader in mind. In the first illustration, the flock of birds dispersing across the sky might well be the rooks depicted by Henry Green. Ducks are sitting on the water in the river scene, one of them upending, i.e. head down and tail up, looking for food on the river bed. Flocks of birds reappear in the sky in the strips summing up the reverse journey. Birdwatching and bird conservation are part of the British cultural heritage, as proven by the active presence of the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds, but not all parents or teachers can identify birds or understand their behaviour in the illustrations. What about foreign parents and teachers who have been reading the book in translation? Do curlews resonate with them?

What about the enormous fallen tree in the forest scene? Helen Oxenbury placed it there to match the requirements of the text and as a reminder of a dramatic crash, but is there something in the exposed root system suggestive of environmental awareness? Given that the illustrator has such a keen eye on nature in the other illustrations, we must consider that option. There is value in calling up incipient about-to-be born contexts when trying to assess the meaning or, as Michael Wood would say “the knowledge”, of a piece, for art is instrumental in producing new contexts and new knowledge. In the case of this illustration, the new knowledge is that dead trees are valuable habitats for animal and plant species, and they should not necessarily be cleared away, a late 20th century approach to forestry management.

As for the dog chosen to complete the family (he faces the bear head on in the cave), it is a border collie, an English breed, which reinforces the identity of the family as English. The children have red or blond hair and the young father figure has light brown / reddish hair. They are all fair-skinned. It would be (too?) easy to argue that Helen Oxenbury’s definition of an English family, or an English adventure, is traditional as far as ethnicity, geography, education and gender is concerned: “Rural scenery is mobilized as a symbol of English national identity: like whiteness or Anglo-Saxon character, they are part of the construction of a legitimate order. Thus the predominant rural image is one of a place that is white, orderly, pacified, unchanging, and so on. (Julian Mischi, 2009, 111). In the conversation filmed by The Guardian for the 25th anniversary of the book Helen Oxenbury says: “There’s no hint of who they are in the text…” Michael Rosen’s quick reply is highly appreciative: “No, no, you did that. You made that family from the word ‘we’.” Indeed despite their bias towards conservatism and the fact that they may perpetuate an ideal and nostalgic vision of England-Britain, the illustrations are an artistic success. They convey movement and action as well as a sense of communication between the characters (something the chorus does not suggest). Although they form a unit, the family members clearly have ideas and thoughts of their own as indicated by their gestures, their bodily positions, their facial expressions… Also the presence of a breeze revealed by the ruffled or floating hair and flapping clothes expresses energy throughout the book – the One life within them and abroad -- the sign of a positive and vibrant mood. We should finally note that Helen Oxenbury departed from the traditional tenet that characters should move from left to right if they are journeying into the future. In the colour pictures she often made her characters move in the opposite direction -- towards the onomatopoeias on the left page. The links between the visual material and the sounds are strengthened. They converge as in theatre or film.

7. A moral reversal

As a final point Helen Oxenbury’s treatment of the bear at the very end brings an unexpected moral twist to the book. The last wordless illustration is her own personal addition to the narrative. It echoes the first two pages of sea at low tide before the title page which, we now understand, were a silent preparation for the dramatic exit. The coastline is an ideal summary of England but also the locus of grief and d/r/ejection. It is now high tide, night time, the sailing boats have disappeared, and the anthropomorphic bear goes home with a heavy heart as suggested by his slumped shoulders, heavy footsteps and his face overshadowed by darkness. The close-up of family togetherness in the previous two pages contrasts strongly, light-wise and colour-wise, with the last image of the humanoid bear. This leads to a shift in the reader’s empathy. Were the bear’s intentions as aggressive as the family and the reader thought? What does the wild animal stand for? How is the child’s moral fibre affected by the last image? Visual literacy is not our subject here, nor is the dialogue between the adult reader, the book and the child which arises when a story is read out loud, but clearly Helen Oxenbury placed a moral question at the end of the narrative which the text supplied by Michael Rosen did not contain.

As a final point Helen Oxenbury’s treatment of the bear at the very end brings an unexpected moral twist to the book. The last wordless illustration is her own personal addition to the narrative. It echoes the first two pages of sea at low tide before the title page which, we now understand, were a silent preparation for the dramatic exit. The coastline is an ideal summary of England but also the locus of grief and d/r/ejection. It is now high tide, night time, the sailing boats have disappeared, and the anthropomorphic bear goes home with a heavy heart as suggested by his slumped shoulders, heavy footsteps and his face overshadowed by darkness. The close-up of family togetherness in the previous two pages contrasts strongly, light-wise and colour-wise, with the last image of the humanoid bear. This leads to a shift in the reader’s empathy. Were the bear’s intentions as aggressive as the family and the reader thought? What does the wild animal stand for? How is the child’s moral fibre affected by the last image? Visual literacy is not our subject here, nor is the dialogue between the adult reader, the book and the child which arises when a story is read out loud, but clearly Helen Oxenbury placed a moral question at the end of the narrative which the text supplied by Michael Rosen did not contain.

The human house with its rug, timber floor and garden gate is a protective shell for the family, where the bear is a manufactured teddy bear, a human construct. The bed is a protective space ("Into bed. Under the covers.") inside another protective space, the house. The last image of a journey back home conveys the idea that the cave is the equivalent for the bear. When the family tiptoes inside the cave, they invade the bear's territory. They trespass. Physical, moral, environmental trespassing is implied. A children’s book does not preclude dark possibilities, but they are left incipient by the writer or the illustrator, and can be left unspoken and undiscussed by the adult and the child reader.

The human house with its rug, timber floor and garden gate is a protective shell for the family, where the bear is a manufactured teddy bear, a human construct. The bed is a protective space ("Into bed. Under the covers.") inside another protective space, the house. The last image of a journey back home conveys the idea that the cave is the equivalent for the bear. When the family tiptoes inside the cave, they invade the bear's territory. They trespass. Physical, moral, environmental trespassing is implied. A children’s book does not preclude dark possibilities, but they are left incipient by the writer or the illustrator, and can be left unspoken and undiscussed by the adult and the child reader.

Conclusion

If one hears the story or watches the story being delivered by Michael Rosen, "we" could be many different groups of people (or animals, or animated objects). Helen Oxenbury chose to feature a modern family with a dog. She thought she was representing her teenage son, but the character turned out to look more like a father than a sibling, which made that aspect of the book open to interpretation. She also chose a particular rural context for the story and she chose watercolour as her main medium of artistic expression. She felt free and inspired to place her own visual foreword and her own visual afterword at both ends of the book. She added a considerable amount of material to the narrative which can be commented on through the prism of cultural studies, history or politics. Tradition and counter-tradition occur because individuals make decisions (either conscious or unconscious) to remain within a given path or to depart from it. She did both. The text supplied and improved by Michael Rosen has its own say on the difference between stamina and bravado but the visual representation of the male adult hiding blissfully in bed under a pink eiderdown takes the question a little further into the realm of gender politics. The last picture of the Other also invites further pondering. Fear may have retreated in the child’s mind, but the last picture suggests that encounters between complete strangers are no simple matter.

Bibliographie

ANONYMOUS. Beowulf. No date. British Library Website. http://www.bl.uk/onlinegallery/onlineex/englit/beowulf/index1.html

BROWNE, Anthony. 2004. Into the Forest. London; Walker Books Ltd.

DICKENS, Charles. 1998 (1859). A Tale of Two Cities. London, Oxford World's Classics.

DRABBLE, Emily, SPRENGER, Richard & SMITH, Elliot. April 10, 2014. ‘We're Going on a Bear Hunt: The editors were so excited they were nearly weeping’. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/books/video/2014/apr/10/we-re-going-on-a-bear-hunt-michael-rosen-helen-oxenbury-video

EL-TAMANI, Wiam. 2007. ‘The Simple Little Picture Book: Private Theater to Postmodern Experience’, Alif: Journal of Comparative Poetics 27. 25-43.

MISCHI, Julian. 2009. ‘Englishness and the Countryside. How British Rural Studies Address the Issue of National Identity’. In REVIRON-PIEGAY, Floriane (ed.). Englishness Revisited. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing. 109-125.

NODELMAN, Perry. 2008. The Hidden Adult. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University.

PEPPER SINKLER, Rebecca. November 21, 1999. ‘Curiouser and Curiouser’. The New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/books/99/11/21/reviews/991121.21sinklet.html

STRONG, Roy. 2011. Visions of England. London: The Bodley Head.

TIMS, Anna. November 5, 2012. ‘Helen Oxenbury and Michael Rosen on We're Going on a Bear Hunt’, The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/books/2012/nov/05/how-we-made-bear-hunt

WOOD, Michael. 2005. Literature and the Taste of Knowledge. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

WOOLF, Virginia. Orlando. 1986 (1928), London: Grafton Books.

The illustrations in this article are reproduced by kind permission of Walker Books Ltd:

Text © 1989 Michael Rosen

Illustrations © 1989 Helen Oxenbury

From WE’RE GOING ON A BEAR HUNT by Michael Rosen & Illustrated by Helen Oxenbury

Reproduced by permission of Walker Books Ltd, London

www.walker.co.uk

Pour citer cette ressource :

Véronique Alexandre, We’re Going on a Bear Hunt: Traditional and Counter-traditional Aspects of a Classic Children’s Book, La Clé des Langues [en ligne], Lyon, ENS de LYON/DGESCO (ISSN 2107-7029), juillet 2017. Consulté le 26/02/2026. URL: https://cle.ens-lyon.fr/anglais/litterature/litterature-britannique/litterature-jeunesse/we-re-going-on-a-bear-hunt-traditional-and-counter-traditional-aspects-of-a-classic-children-s-book

Activer le mode zen

Activer le mode zen