Brexit and the challenges of the Irish border

URL : http://geoconfluences.ens-lyon.fr/actualites/eclairage/brexit-frontiere-irlandaise/

The results of the Brexit referendum of 23 June 2016 revealed a heavily polarised country – geographically, demographically, socially and economically – and clearly challenged the United Kingdom’s unity, confirming the existence in the UK of a deep crisis affecting the European project, the British identity, the political system and the democratic process.

There was little debate about the Northern Irish border issue during the referendum campaign. It only came to the fore during the next phase, which was to prepare the UK's exit from the European Union in March 2019. The border is not only the largest land border between the United Kingdom and the European Union, but it is also marked by the history of a bitter conflict, although community relations in Northern Ireland have significantly improved in the last 20 years. The reinstatement of a hard border between Northern Ireland under British sovereignty and the Republic of Ireland could be experienced by cross-border commuters and residents of both territories as a painful step backwards.

The Irish border issue sums up all the contradictions of Brexit – it is impossible for the United Kingdom to maintain a completely open border while reinstating border checks on people and goods. This article shows that these contradictions are tightly linked to the uncertainties of Brexit and the historical context of community conflict in Northern Ireland.

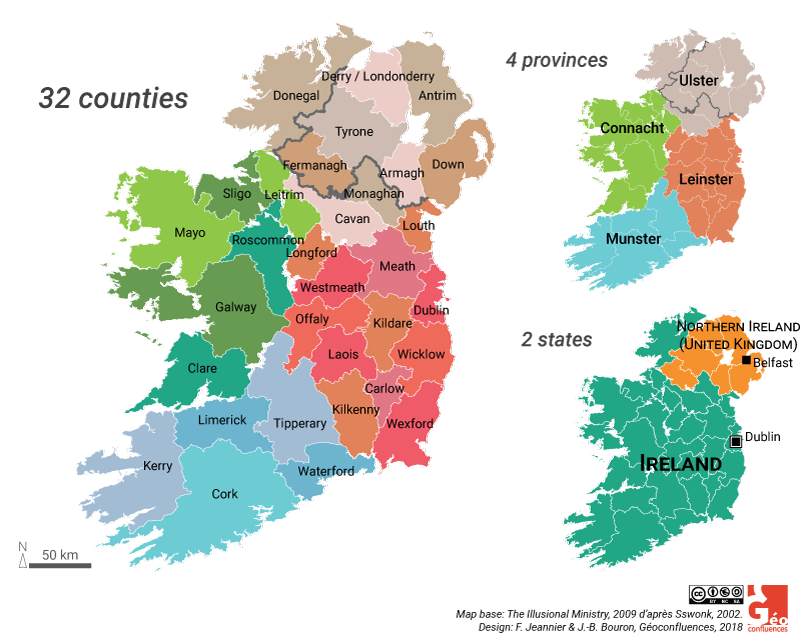

Figure 1. Provinces and counties in Ireland and Northern Ireland

1. Brexit and Northern Ireland: a very specific context

Britain as a whole voted to leave the European Union (EU) by 51.9% to 48.1%. However, the two minority nations [1] – Scotland and Northern Ireland – voted to remain in the EU. The case was clear in Scotland where not a single constituency voted in favour of Leave, with an overall 62% in favour of Remain (with a turnout of 67.2%).

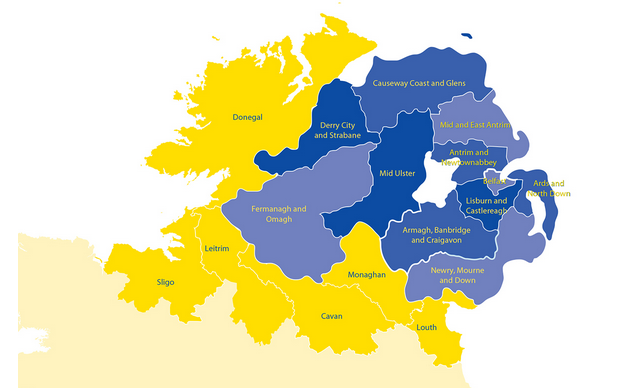

In Northern Ireland, the result was not so clear-cut, even though it came out that 55.8% of people voted in favour of Remain (with a turnout of 62.7%). Only 7 of the 18 Northern Irish parliamentary constituencies voted in favour of Leave, the constituency of North Antrim leading the way with 62.2%. Interestingly, all the constituencies bordering the Republic of Ireland voted to remain in the EU, with comfortable margins ranging from 58.6% in Fermanagh and South Tyrone and a striking 78.3% in Foyle. In addition, three of the ten unionist constituencies voted in favour of Remain, when all the nationalist constituencies returned a Remain vote.

| Population 2017 | Share of UK population | Brexit result | |

|---|---|---|---|

| England | 55 619 400 | 84.4% |

Leave — 53.4%

|

| Wales | 3 125 200 | 4.7% |

Leave — 52.5%

|

| Scotland | 5 424 800 | 8.2% |

Remain — 62.0%

|

| Northern Ireland | 1 870 800 | 2.8% |

Remain — 55.8%

|

| UK | 66 040 200 | 100.00% |

Leave — 51.9%

|

| Ireland | 4 761 865 (April 2016) |

Insert 1 – Unionists and nationalists

In Northern Ireland, the term unionist refers to the part of the population that wants Northern Ireland to remain one of the four nations of the United Kingdom, thus maintaining close links with the British Crown. One also speaks of loyalist, although the two terms are not interchangeable. Indeed, the term loyalist applies to individuals who advocate a more uncompromising unionism and who support or engage in violent militancy. Being a unionist does not automatically mean being a loyalist. Unionists and loyalists generally belong to the Protestant community of Northern Ireland.

Nationalists advocate the reunification and independence of Ireland, through purely democratic and peaceful means. Republicans are the most militant fringe of nationalists, associated with the Sinn Féin political party and the violence of the Irish Republican Army (IRA). Nationalists and Republicans belong to the Catholic community of Northern Ireland.

As far as British home affairs were concerned, two of the major issues that immediately emerged from the results of the Brexit referendum were:

- the independence of Scotland – the Scottish National Party in office immediately announced that the clear majority of Remain in Scotland challenged the result of the 2014 referendum of independence and that a second referendum for independence could be organised much sooner than expected;

- the Irish border, which happens to be the only land border between the UK and the EU (except specific cases such as Gibraltar and British military bases in Cyprus).

Newly-elected Leader of the Conservative Party Theresa May famously said on July 11th, 2016, less than a month after the Brexit referendum, addressing her supporters in Birmingham, that “Brexit means Brexit”. She added that “we are going to make a success of it. There will be no attempt to remain inside the EU. There will be no attempt to rejoin it by the back door, no second referendum. The country voted to leave the European Union and as Prime Minister I will make sure that we leave the European Union" [2]. Whatever the real meaning of Theresa May’s aphorism, the reality reality is that the negotiations between the British Government and the European Union since the United Kingdom triggered, on March 29th, 2017, Article 50 of the Treaty on European Union which enables a member state to withdraw from the European Union, have proven very difficult. Among many of the very tricky issues to tackle, the question of the Irish border has undoubtedly been the most disputed [3]. The absence of a solution for the Irish border could eventually lead to a “no-deal Brexit”, meaning that Brexit would abruptly take effect on March 29th, 2019, without a transition period. The United Kingdom would therefore be considered as a third country by the European Union. The aim of this contribution is to shed light on the key issues related to the Irish border that have made the negotiations between the British Government and the European Union particularly complex and thorny.

| Constituency | MP's political affiliation | Brexit result |

|---|---|---|

| West Tyrone | Sinn Féin |

Remain — 66.8%

|

| Belfast West | Sinn Féin |

Remain — 74.1%

|

| Fermanagh and South Tyrone | Sinn Féin |

Remain — 58.6%

|

| South Down | Sinn Féin |

Remain — 67.2%

|

| Newry and Armagh | Sinn Féin |

Remain — 62.2%

|

| Foyle | Sinn Féin |

Remain — 78.3%

|

| Mid Ulster | Sinn Féin |

Remain — 60.4%

|

| North Down | Independent |

Remain — 52.4%

|

| East Londonderry | Democratic Unionist Party |

Remain — 52.0%

|

| Belfast North | Democratic Unionist Party |

Remain — 50.4%

|

| Belfast South | Democratic Unionist Party |

Remain — 69.5%

|

| Belfast East | Democratic Unionist Party |

Leave — 51.4%

|

| Lagan Valley | Democratic Unionist Party |

Leave — 53.1%

|

| North Antrim | Democratic Unionist Party |

Leave — 62.2%

|

| East Antrim | Democratic Unionist Party |

Leave — 55.2%

|

| South Antrim | Democratic Unionist Party |

Leave — 50.6%

|

| Strangford | Democratic Unionist Party |

Leave — 55.5%

|

| Upper Bann | Democratic Unionist Party |

Leave — 52.6%

|

Figure 2. EU referendum results in Northern Ireland 26 June 2016

Insert 2 – A short history of a border

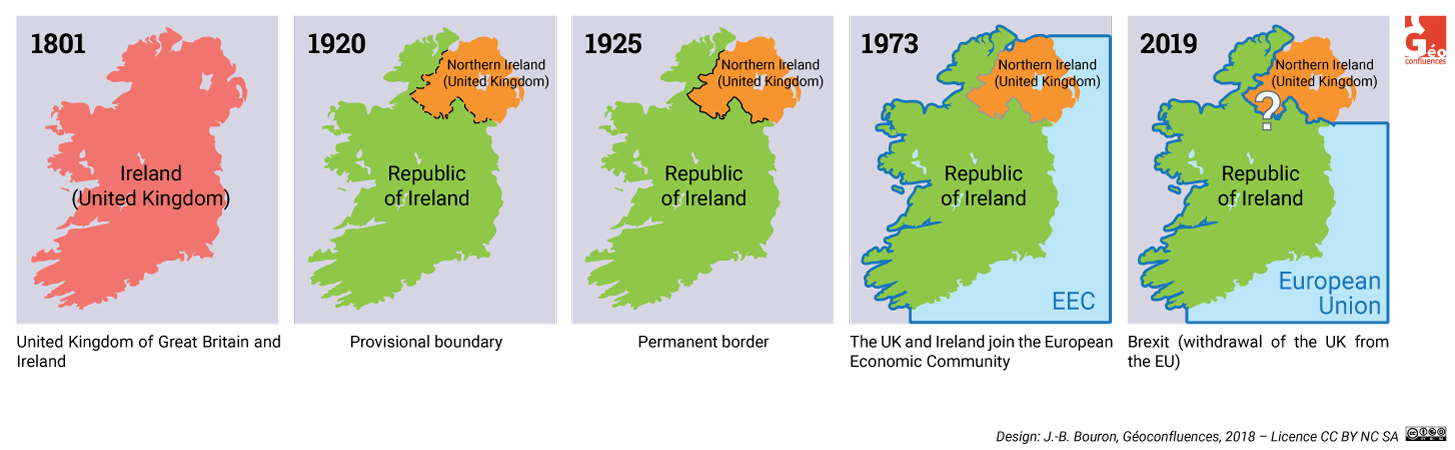

Today’s border between the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland (and therefore the UK) dates back to the Government of Ireland Act of 1920 which partitioned Ireland. It was established by the Act as a provisional border. The 1920 Act made provision for an Irish boundary commission whose task was to decide on the precise delineation of the border between the Irish Free State and Northern Ireland, in case Northern Ireland chose to opt out of the Irish Free State (which was created by the Anglo-Irish Treaty of 6 December 1921) – which it did in December 1922. The commission confirmed the border by the end of 1925. The final agreement between the Irish Free State, Northern Ireland and the UK was signed on 3 December 1925 and then ratified by their respective parliaments. Therefore, the border remained a provisional one for five full years, from the end of 1920 until the end of 1925. The Agreement was then formally registered with the League of Nations on 8 February 1926.

Further Reading: The Making of the Irish Border

As a response to the rebellion of the United Irishmen, an uprising against British rule in Ireland that began in May 1798 and ended five months later in a victory of the British forces, British Prime minister William Pitt the younger engineered the Act of Union between Great Britain and Ireland. He believed that Ireland could not be granted an independent parliament, because the Irish might decide on an independent nation and make Ireland a base for England's enemies. Therefore, Pitt decided on an Act of Union which would totally tie Ireland to Great Britain. The Act of Union, passed by both the Irish and the British parliaments in 1800, became effective on 1 January 1801. As a result, Ireland joined Great Britain into a single kingdom, the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, the Dublin parliament was abolished and the Anglican Church was recognised as the official Church of Ireland. The Act created the first British Parliament.

Direct rule from Westminster solved none of the grievances in Ireland over land, religion or politics. Ireland's social and economic problems were also ignored. Catholic emancipation would have been essential (and was advocated by Pitt) but British peers holding Irish estates opposed concessions to Roman Catholics, as did the British monarch George III, because of vested interests and religious bigotry. Consequently, the Act of Union did not provide for Catholic emancipation. Roman Catholics were therefore not allowed to hold public office, causing increased sectarian bitterness and leading Pitt to resign (See The Victorian Web for a more detailed analysis of the consequences of the 1801 Act of Union and History of Parliament Online for parliamentary intricacies).

The Irish continued to challenge British authority throughout the 19th century. Daniel O’Connell took the issue of Catholic emancipation to the people by setting up the Catholic Association in 1823. The latter turned the issue into a national movement until Catholic emancipation was eventually achieved when the Roman Catholic Relief Act (or Catholic Emancipation Act) passed in parliament and was given royal assent on 13 April 1829. It lifted most civil restrictions for Catholics who could then sit as MPs at Westminster and became eligible for most public offices. However, the emancipation came at a price as the Irish electorate was cut drastically: the 40-shilling (£2) freeholder franchise qualification for Irish county elections was raised to £10, which reduced the number of peasant voters (on the Catholic emancipation, see The Victorian Web and Encyclopedia.com).

The issue of Irish self-government came to prominence in the second part of the 19th century in the form of constitutional/ parliamentary nationalism. The Home Government Association, a pressure group formed in 1870, became a full political party, the Home Rule League, in 1873 and then the Irish Parliamentary Party in 1882. Charles Stewart Parnell, who became the leader of the Home Rule League in 1880, put Home Rule firmly on the parliamentary agenda, but ultimately failed to achieve his goal. Liberal Prime minister Gladstone was also unsuccessful to push through his Home Rule bills. His 1886 bill was defeated in the House of Commons and the 1893 bill was defeated in the House of Lords. A third Home Rule bill was introduced by Liberal Prime minister H. H. Asquith in 1912. It was passed by parliament in May 1914 and given royal assent on 18 September 1914 but its implementation was formally postponed with the outbreak of the First World War. In the end, the Act never took effect.

The beginning of the 20th century saw the resurgence of Irish republicanism. The political party Sinn Féin – “we ourselves” – whose aim was to free Ireland from British rule and gain independence for the whole of Ireland, was created in 1905 and the Irish Republican Brotherhood – an organisation dedicated to the establishment of an independent democratic republic in Ireland (1858-1924) – was revived. However, the fact that Home Rule was likely to become reality in a not-too-distant future limited their appeal at the time, although it was expected that special arrangements would be made for unionist Ulster. As a matter of fact, unionists in Ulster strongly opposed self-government in Ireland from Dublin and began lobbying for the exclusion of six of Ulster's nine counties from the arrangements provided by the third Home Rule bill. In January 1913, Protestant unionist activists founded a paramilitary militia, the Ulster Volunteer Force, making it clear that they would resist any attempt to introduce Home Rule in Ireland. In the same year, as a response to the creation of the UVF, the Republicans formed their own paramilitary militia, the Irish Volunteers, which would become the IRA (Irish Republican Army) in 1919. The spectre of civil war hung over Ireland.

It is in this context of increasing sectarian bitterness that the Military Council of the Irish Republican Brotherhood planned an uprising, working on the principle that, while Britain was distracted by the war in Europe, there would be no better opportunity to strike for an independent Ireland. The Easter Rising of 1916 led to heavy fighting in the centre of Dublin. The republican leaders, led by Patrick Pearse and James Connolly amongst others, proclaimed an Irish Republic but the rebellion was crushed by the British army and most of its leaders were promptly executed. The Easter Rising was the most significant uprising in Ireland since the rebellion of 1798. It brought physical force republicanism back to the forefront of Irish politics (the Irish revolutionary period is usually defined as starting in 1912 and finishing in 1923. However, the period is sometimes more narrowly defined as running from 1916 - The Easter Rising - to 1921 - the end of the Irish War of Independence or Anglo-Irish War) and was highly instrumental in creating a dramatic shift in public opinion in favour of the republican cause. One of the surviving leaders of the Easter Rising, Éamon de Valera, was elected president of Sinn Féin in October 1917, unifying all groups working towards an independent Ireland under a single leadership.

The Irish War of Independence broke out on 21 January 1919 when members of the Irish Volunteers killed two members of the Royal Irish Constabulary in an ambush near Tipperary Town. On the same day, the Dáil Éireann – an assembly of 27 Sinn Féin Members of Parliament elected at the British general election of 1918 who refused to sit at Westminster but decided to form an Irish assembly – met for the first time. The ambush had not been ordered by the Dáil but the course of events soon drove it to recognise the Volunteers as the army of the Irish Republic and the ambush as an act of war against Great Britain. The first Dáil issued a Declaration of Independence and proclaimed an Irish Republic in January 1919. The Irish Volunteers became the IRA in August 1919 and went on waging a guerrilla war against British forces under the leadership of Michael Collins, who served simultaneously as minister of finance in the Dáil and director of intelligence for the IRA.

Meanwhile, the British government tried to solve the Irish question which had been shelved since the outbreak of the First World War by pushing through Home Rule legislation once more. Liberal Prime Minister David Lloyd George introduced a fourth Home Rule Bill to parliament which was approved in November 1920. The Government of Ireland Act of 1920 was passed on the 23rd December 1920 and established the partition of Ireland as it was designed to create two self-governing territories within Ireland, Southern Ireland and Northern Ireland, each with its own parliament and governmental institutions, and both remaining within the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. Southern Ireland was to be all of Ireland (26 counties) except for the six parliamentary counties of Antrim, Armagh, Down, Fermanagh, Londonderry and Tyrone, and the parliamentary boroughs of Belfast and Londonderry – they were to constitute Northern Ireland. Northern Ireland was therefore devised to be composed of six of the nine counties of Ulster, where unionists could be expected to have a safe majority (consequently excluding Donegal, Cavan and Monaghan). Provisions were made in the Act for future unification through a Council of Ireland.

However, when the Government of Ireland Act came into force on 3 May 1921 it was already out of touch with realities in Ireland. The War of Independence and the existence of Dáil Éireann meant that the proposed Dublin Home Rule parliament was never established in Southern Ireland – the separatist Irish parliament established in Dublin did not recognise the Government of Ireland Act. The long-standing demand for home rule had been replaced among nationalists by a demand for complete independence while the Irish War of Independence or Anglo-Irish War was reaching a peak of violence.

By July 1921, the conflict had hit a stalemate. A truce was signed by the belligerents on 11 July 1921 and negotiations took place over the following months between Irish nationalist leaders and the British government. They resulted in the Anglo-Irish Treaty signed in London on 6 December 1921 and ratified by the second Dáil in January 1922. In accordance with the treaty, on 6 December 1922 the entire island of Ireland became a self-governing Dominion of the British Empire called the Irish Free State, meaning that it was a constitutional monarchy sharing a monarch with the United Kingdom and the other Dominions of the British Commonwealth. In other words, the treaty explicitly ruled out a republic. Under the Constitution of the Irish Free State, the Parliament of Northern Ireland which had been opened by King George V on 22 June 1921 at Belfast City Hall had the option to leave the Irish Free State one month later and return to the United Kingdom. It took the Parliament of Northern Ireland only two days to make its decision. By 8 December 1922, Northern Ireland had opted out of the Irish Free State (see the very complete website at the National Archives of Ireland: http://treaty.nationalarchives.ie/)

Today’s border between the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland (and therefore the UK) dates back to the Government of Ireland Act of 1920 which partitioned Ireland, although the border was originally intended as an internal boundary within the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. It was established by the Act as a provisional border whose legal existence as an international border started when the parliament of Northern Ireland decided to exercise its right to opt out of the Irish Free State on 8 December 1922.

The 1920 Act made provision for an Irish boundary commission whose task was to decide on the precise delineation of the border between the Irish Free State and Northern Ireland, in case Northern Ireland chose to opt out of the Irish Free State. The commission was appointed in 1924, met in 1925 and the existing border was confirmed by the end of 1925. The final agreement between the Irish Free State, Northern Ireland and the UK was signed on 3 December 1925 and then ratified by their respective parliaments (the commission report was not published until 1969). Therefore, the border remained a provisional one for five full years, from the end of 1920 until the end of 1925. The Agreement was then formally registered with the League of Nations on 8 February 1926.

Figure 3. The history of the Irish border in five maps

2. The failure of a painstakingly negotiated and fiercely contested withdrawal agreement

British Prime Minister Theresa May confirmed in January 2017 the British government’s plans for a hard Brexit, stating that Britain’s control of EU immigration and its withdrawal from the jurisdiction of the European Court of Justice remained her government’s top priorities. Mrs May clearly stated that the UK wanted to take back control of its laws. Consequently, Britain would not be able to stay in the single market. As a matter of fact, the British government’s objectives are incompatible with membership of the single market, since the EU has made it clear that it means accepting the EU’s four freedoms – the free movement of people, goods, capital and services – and complying with the EU’s rules and regulations that regulate those freedoms (Source: The Guardian). This would obviously be in contradiction with Mrs May’s statement. In addition, Mrs May announced the UK’s intention to withdraw from the customs union.

The British government’s commitment to a hard Brexit has been seriously challenged since Theresa May triggered Article 50. The inflexibility of the EU and the debate in the UK between hard Brexiters and soft Brexiters have put a lot of pressure on Mrs May and her government, leading to several governmental crises.

What is more, the current domestic political context is unfavourable to Mrs May – her government had to secure a “confidence and supply agreement” with the Northern Irish Democratic Unionist Party (DUP – the DUP is strongly Eurosceptic and so in favour of leaving the EU, socially conservative and staunchly opposed to any form of loosening the tie between Northern Ireland and the rest of the UK) to form a minority government following the inopportune and untimely general election of June 2017 after which the Conservatives lost their majority at the House of Commons [4]. Mrs May’s Conservative party needs the DUP to reach a very short majority at the House of Commons (the Conservative party holds 316 seats and the DUP 10 seats, for a total of 326 out of 650 seats).

After months of negotiations (and dead ends), UK and EU negotiators reached a "draft withdrawal agreement" presented by Theresa May to her government, which endorsed it, on 14 November 2018. On the European side, the agreement was unanimously approved by the 27 heads of state on 25 November 2018. It was to be submitted to the British Parliament for ratification on 12 December 2018. As soon as the text was published, its approval proved to be very uncertain, given the dissatisfaction it aroused among the advocates of a hard Brexit and North Irish unionists. A hundred or so Conservative MPs said they would vote against the agreement, causing a major political crisis. Theresa May had to postpone the vote before successfully facing a no-confidence vote in the Conservative party questioning her position as party leader, and therefore her post of Prime Minister. However, the problem remained unresolved for Theresa May, who promised not to lead the Conservative party campaign in the next general elections, which will take place in May 2022 at the latest, but was then forced to obtain very hypothetical additional assurances from the European Union as to the temporary nature of the "backstop" for the withdrawal agreement to be voted by the British Parliament. It is obviously too late to take up more ambitious negotiations. The vote finally took place on 15 January 2019. The British Parliament overwhelmingly voted against Theresa May’s Brexit deal, triggering another political crisis (the Prime Minister narrowly survived a second no-confidence vote, tabled by the leader of the Labour opposition Jeremy Corbyn, on the following day) and the perspective of the absence of a deal between the United Kingdom and the European Union.

Although it was rejected by the British Parliament, this agreement – which is strengthened by a political declaration outlining the future relations between the United Kingdom and the European Union in the areas of trade and security – remains an important document for the future relations between the two parties, especially in the case of (possible) new negotiations. The draft withdrawal agreement details the conditions under which the United Kingdom would have left the European Union on 29 March 2019, while opening a transition period ending on 31 December 2020 (with the possibility of a one- or two-year extension), to allow administrations, businesses and citizens to adjust to the withdrawal. During this period, the European Union rules would have continued to apply to the United Kingdom, which would have remained a member of the customs union and the single market. However, the United Kingdom would have ceased to participate in the decision-making process of the European Union.

The agreement contains a long (21 articles, 144 pages of annexes) specific protocol on Ireland and Northern Ireland whose objective is to build a “backstop” to prevent the return of a border (that is to say physical infrastructures and checks) between Ireland and Northern Ireland and to preserve the provisions of the 1998 Good Friday Agreement, the cooperation between the two territories and the island economy in the event that the United Kingdom and the European Union would have failed, after the transitional period, to seal a definitive Free Trade Agreement, which was to be concluded and ratified by 1 July 2020. Under the terms of the November 2018 draft withdrawal agreement, in the absence of a Free Trade Agreement at the end of the transition period and of a technological solution to avoid border controls and preserve the total fluidity of exchange on the island, the United Kingdom would have remained in the customs union with the European Union, forming "a single EU-UK customs territory", and Northern Ireland would have remained aligned to a limited set of rules that are related to the single market for an indefinite period, unless and until another agreement was accepted by both parties. In other words, the conditions set out in this specific protocol on Ireland and Northern Ireland would have ruled the economic relations between the United Kingdom and the European Union from 1 January 2021, if the transition period were not extended and no other agreement were accepted by the two parties to replace the backstop. In this case, the Irish Sea would have become the border between Ireland and Great Britain: products from the United Kingdom would have had to be controlled as they entered Northern Ireland to check that they met European norms and regulations. The backstop also provided for the UK to abide by a number of rules to ensure that there would be a “level playing field” within the European Union.

The “backstop” was a key element in the rejection of the agreement by the British Parliament. It was impossible for hard Brexiters and the DUP to accept such dispositions as they argued that the backstop would have seriously threatened the constitutional integrity of the United Kingdom since it would have introduced a difference of treatment between Great Britain and Northern Ireland, which could have in practice ended up in a customs union with the European Union. According to the supporters of a hard Brexit, this would also have meant that the link with the European Union would not have been severed: the United Kingdom would have remained "shackled" to the latter for an indefinite period (the United Kingdom would have been, according to the Attorney General, likely to be trapped in protracted and repeated rounds of negotiations in the years ahead with the European Union because it could not leave the "backstop" without its agreement), would have been obliged to follow European directives without being able to influence their definition and would be prisoner of an agreement prohibiting it from negotiating bilateral trade agreements with other countries.

See European Union infographics

The backstop explained

The Irish border issue was far from being settled by the November 2018 agreement. It is obviously even less so now that the agreement has been formally rejected by the British Parliament. The only certainty so far was that the United Kingdom and the European Union had reaffirmed their determination to avoid the reinstatement of a border between Ireland and Northern Ireland, in order to preserve the stability of community relations in Northern Ireland and the free movement of people and trade on the island. A new period of uncertainties opens up. Will the United Kingdom and the European Union be consistent with their intentions and what will the practical solutions be? In any case, these three major issues undoubtedly remain relevant.

3. Three major issues: the peace process, the movement of people and the economy

3.1 The peace process

Since the signing of the Good Friday Agreement (also known as the Belfast Agreement or British-Irish Agreement), Northern Ireland has been a post-conflict society where community relations have remained a key issue. The political system is characterised by stalemate and logjam and is very much hampered by the internal structure of the institutions (the ethnic dual-party system) and the hostility between the two main parties (the euro-sceptic pro-Brexit Democratic Unionist Party and the pro-EU Sinn Féin). It is impossible now to determine the extent to which political relationships in Northern Ireland will be affected by Brexit but the latter will surely deal a strong blow to the Fresh Start Agreement signed by Northern Ireland’s five main political parties and the British and Irish governments in November 2015 after 10 weeks of intense talks. The agreement itself is presented as “an agreement to consolidate the peace, secure stability, enable progress and offer hope.” It was urgent to address the political crisis that had been taking place in Northern Ireland over welfare reform (in particular the implementation of the Stormont House Agreement (SHA) of 23 December 2014 [5]) and (the legacy and impact of) paramilitary activity and sectarianism.

Declaration of the Irish Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade in November 2015

“Building on the Stormont House Agreement of December 2014, Fresh Start constituted another significant step towards normalising politics and society in Northern Ireland and consolidating hard won peace for the island of Ireland which was achieved with the 1998 Good Friday Agreement. The Fresh Start Agreement provides a credible roadmap for the implementation of many aspects of the Stormont House Agreement (including those on parading and flags) and supports the ongoing stability of the devolved power-sharing institutions so that they can deliver for the people of Northern Ireland.”

Source: https://www.dfa.ie/annualreport/2015/our-people/fresh-start-agreement/ [6]

The stability of community relations is the first major challenge raised by Brexit as the peace process in Northern Ireland might be threatened by the return of a border which would stand against the terms of the Good Friday Agreement and would revive the memories of the Troubles and the partition of Ireland in 1921. From a nationalist point of view, the return of a border is unacceptable for it would make the reunification of Ireland even more hypothetical than it already is. They advocate a special status, which in turn is unacceptable from a unionist point of view, as the latter would consider it as a breach in the unity of the UK. It would also be a strong reminder of the period of the Troubles. It is the reason why the United Kingdom and the European union have to agree on a solution that avoids the reinstatement of a border with physical infrastructures between the two Irish territories, as it is clearly reaffirmed in the Protocol on Ireland and Northern Ireland.

Figure 4. Flags and symbols in Northern Irish urban landscapes

|

|

|

|

|

|

The EU has been a significant political, economic and psychological factor (through the PEACE and INTERREG programmes) that has enabled unionists and nationalists to collaborate and has been a means of maintaining relationships with the Republic of Ireland [7]. It is likely that the institutions built around the peace process would be seriously undermined if the European frameworks upon which they are dependent were removed by UK exit from the EU [8]. The devolution process, a key component of the Belfast Agreement, is tightly bound to the EU and the European Convention on Human Rights. The question is therefore to evaluate the extent to which these institutions will be able to adjust to different legal frameworks and will be able to pursue cross-border collaboration.

Insert 3 - PEACE IV Programme overview

The €270m PEACE IV Programme is a unique initiative of the European Union which has been designed to support peace and reconciliation. The PEACE Programme was initially created in 1995 as a direct result of the EU's desire to make a positive response to the paramilitary ceasefires of 1994. Whilst significant progress has been made since then, there remains a need to improve cross-community relations and where possible further integrate divided communities. The new programming period for 2014-2020 provides opportunity for continued EU assistance to help address the peace and reconciliation needs of the region.

In total 85% of the Programme, representing €229m, is provided through the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF). The remaining €41m, representing 15% is match-funded by the Irish Government and the Northern Ireland Executive. The eligible area for the PEACE IV Programme for 2014-2020 is Northern Ireland and the Border Counties of Ireland (including Cavan, Donegal, Leitrim, Louth, Monaghan and Sligo).

The content of the new PEACE IV Programme has been agreed by the Northern Ireland Executive, the Irish Government and the European Commission. It has four core objectives where it will make real and lasting change in terms of Shared Education initiatives, Support for marginalised Children and Young People, the provision of new Shared Spaces and Services, and projects that will Build Positive Relations with people from different communities and backgrounds.

| Programme | Funding Period | EU Contribution (€m) | National Contribution (€m) | Total Programme Value (€m) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PEACE I | 1995-1999 | 500 | 167 | 667 |

| PEACE II | 2000-2004 | 531 | 304 | 835 |

| PEACE II Extension | 2005-2006 | 78 | 82 | 160 |

| PEACE III | 2007-2013 | 225 | 108 | 333 |

| PEACE IV | 2014-2020 | 229 | 41 | 270 |

| Total | 1995-2020 | 1 563 | 702 | 2 265 |

Figure 5. The PEACE IV programme in Irish and Northern Irish counties

Figure 6. The Peace Bridge across the River Foyle in Derry/ Londonderry

EU institutions have played a major supporting role in dealing with the legacy of the Troubles through specific funding, which was made easier by EU membership of both the UK and Ireland. The peace process was sold to and accepted by the population and each community in a specific context that will not exist anymore. As a result, it has been suggested that the revival of violence from paramilitaries could be a consequence of the uncertainties brought in by Brexit. The economic impact of Brexit may have consequences on the relationships between unionists and nationalists: in case of (very likely) negative effects (see below), the most economically vulnerable part of Northern Irish society is likely to be the hardest hit by Brexit. This part of the population was also the most prone to violence during the Troubles [9].

“Even if it is difficult to make the case that the peace process depends directly on EU membership, indirect EU influence has been strong since the EU encouraged unionists and nationalists in Northern Ireland, as well as the UK and Ireland, to work together. Northern Ireland’s EU membership has been a key psychological and political factor in this process. First, common EU membership has enabled the UK and Ireland to improve their relations. The experience of participating as equals in European institutions has helped build trust, highlight shared interests and discuss Northern Ireland. Second, EU membership has diluted the concept of sovereignty of Ireland and eased tensions between unionists and nationalists, as exemplified by the creation of the North-South and East-West institutions in 1998. Multi-level governance has contributed to this more nuanced understanding of sovereignty insofar as it has given Northern Ireland a way to bypass the British State by using the European level to be heard. Brexit could consequently deprive the British and Irish governments of the EU as a neutral space where they could collaborate, and it could revive inter-communal tensions.”

Carine Berberi, « Northern Ireland: Is Brexit a Threat to the Peace Process and the Soft Irish Border? », Revue Française de Civilisation Britannique [En ligne], XXII-2 | 2017.

As an answer to this very specific challenge, the White Paper presented in July 2018 to the House of Commons by Theresa May stated that “the UK remains committed to delivering a future PEACE programme to sustain vital work on reconciliation and a shared future in Northern Ireland. The UK welcomes the European Commission's commitment to a future programme protecting this work and broader cross-border cooperation, and is committed to finalising the framework for this programme jointly over the coming months.” (p. 77).

The Protocol on Ireland and Northern Ireland contained in the November 2018 Withdrawal Agreement effectively recalls the existence of the PEACE and INTERREG programs, and clearly expresses the willingness of the parties to respect the objectives of reconciliation and stability of relations on the island of Ireland, as well as all the obligations defined by the Good Friday agreement, particularly in the field of cross-border cooperation (see in particular Articles 4 and 13). As it is though, it seems that the practicalities related to community relations are still to be addressed (this was already the case in the British government's White Paper). In the field of community relations, financial help from London is far from being secure in the long term to replace EU funds.

The significance of the Good Friday Agreement of 1998

During the Troubles (1968-1998), the border between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland was heavily militarized for obvious security reasons. In some areas the border became dominated by the army watch towers, heavily fortified RUC (Royal Ulster Constabulary) and army buildings, and police and army check points. All along the border minor roads were made impassable by the security forces with concrete blocks, craters, and metal spikes. Approved routes were subject to permanent army and police check points. There were only about 20 approved border crossings.

The Troubles were brought to an end by the Good Friday Agreement (GFA) or British-Irish Agreement, a multi-party and international agreement which was signed in Belfast on 10 April 1998 by most of Northern Ireland's political parties and the British and Irish governments, represented respectively by British Prime Minister Tony Blair and Irish Prime Minister (Taoiseach) Bertie Ahern. Since the GFA, the border between the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland has been a soft border that is invisible, allowing control-free movements of people and goods. Northern Ireland’s last watchtower was removed in 2007, “in a significant symbolic step towards erasing the visible reminders of the province’s 30-year conflict” (see Last of Northern Ireland's watch towers removed on Reuters).

The GFA is the cornerstone of the peace process in Northern Ireland and today’s soft border between the two territories is undoubtedly a major symbol of successful peace building fostered by the GFA.

It is essential to remember that the GFA was a complex balancing act in which issues related to sovereignty and civil and cultural rights were central and whose cross-border scope makes the existence of a border between the two territories irrelevant. The GFA created rights for all communities on the island of Ireland based on devolved, national, international and supranational dimensions. These rights partially derive from EU law and include human right protection based on the European Convention on Human Rights. As a matter of fact, both Ireland and the UK were members of the EU when the GFA was drafted and the GFA largely presupposed that they would remain so. The fact of both the UK and Ireland being in the EU underpins and significantly delivers on the GFA requirement that rights in Northern Ireland mirror those in Ireland, and vice versa. Ireland and Northern Ireland are both subject to the fundamental rights jurisprudence of the Court of Justice of the European Union that is part of EU law’s general principles.

The GFA was conceived as a “fresh start” to foster “reconciliation, tolerance, and mutual trust, and […] the protection and vindication of the human rights of all”. It laid emphasis on the commitment of the British and Irish governments to promote “partnership, equality and mutual respect as the basis of relationships within Northern Ireland, between North and South, and between [the British Isles]” and their “total and absolute commitment to exclusively democratic and peaceful means of resolving differences on political issues, and [their] opposition to any use or threat of force by others for any political purpose, whether in regard to this agreement or otherwise”.

The GFA explicitly recognised the legitimate diversity of identities, traditions and political aspirations in the island of Ireland. The agreement specifically acknowledged as being completely legitimate that the majority of the people of Northern Ireland wished to remain a part of the United Kingdom while a substantial section of the people of Northern Ireland, and the majority of the people of the island of Ireland, wished to bring about a united Ireland.

The GFA left the issue of future sovereignty over Northern Ireland open-ended. The agreement reached was that Northern Ireland was part of the United Kingdom, and would remain so until a majority of the people both of Northern Ireland and of the Republic of Ireland wished otherwise. Should that happen, then the British and Irish governments would be under “a binding obligation” to implement that choice.

“The people of Northern Ireland” were also explicitly recognised the right to "identify themselves and be accepted as Irish or British, or both”. In addition, “their right to hold both British and Irish citizenship [was to be] accepted by both Governments and would not be affected by any future change in the status of Northern Ireland”. By the words “people of Northern Ireland" the Agreement meant “all persons born in Northern Ireland and having, at the time of their birth, at least one parent who is a British citizen, an Irish citizen or is otherwise entitled to reside in Northern Ireland without any restriction on their period of residence”.

The GFA also stated that the power of the sovereign government with jurisdiction in Northern Ireland would be exercised with “rigorous impartiality on behalf of all the people in the diversity of their identities and traditions and shall be founded on the principles of full respect for, and equality of, civil, political, economic, social and cultural rights, of freedom from discrimination for all citizens, and of parity of esteem and of just and equal treatment for the identity, ethos and aspirations of both communities”.

The Northern Ireland Peace Agreement

CONSTITUTIONAL ISSUES

- The participants endorse the commitment made by the British and Irish Governments that, in a new British-Irish Agreement replacing the Anglo-Irish Agreement, they will:

(i) recognise the legitimacy of whatever choice is freely exercised by a majority of the people of Northern Ireland with regard to its status, whether they prefer to continue to support the Union with Great Britain or a sovereign united Ireland;

(ii) recognise that it is for the people of the island of Ireland alone, by agreement between the two parts respectively and without external impediment, to exercise their right of self-determination on the basis of consent, freely and concurrently given, North and South, to bring about a united Ireland, if that is their wish, accepting that this right must be achieved and exercised with and subject to the agreement and consent of a majority of the people of Northern Ireland;

(iii) acknowledge that while a substantial section of the people in Northern Ireland share the legitimate wish of a majority of the people of the island of Ireland for a united Ireland, the present wish of a majority of the people of Northern Ireland, freely exercised and legitimate, is to maintain the Union and, accordingly, that Northern Ireland’s status as part of the United Kingdom reflects and relies upon that wish; and that it would be wrong to make any change in the status of Northern Ireland save with the consent of a majority of its people;

(iv) affirm that if, in the future, the people of the island of Ireland exercise their right of self-determination on the basis set out in sections (i) and (ii) above to bring about a united Ireland, it will be a binding obligation on both Governments to introduce and support in their respective Parliaments legislation to give effect to that wish;

(v) affirm that whatever choice is freely exercised by a majority of the people of Northern Ireland, the power of the sovereign government with jurisdiction there shall be exercised with rigorous impartiality on behalf of all the people in the diversity of their identities and traditions and shall be founded on the principles of full respect for, and equality of, civil, political, social and cultural rights, of freedom from discrimination for all citizens, and of parity of esteem and of just and equal treatment for the identity, ethos, and aspirations of both communities;

(vi) recognise the birthright of all the people of Northern Ireland to identify themselves and be accepted as Irish or British, or both, as they may so choose, and accordingly confirm that their right to hold both British and Irish citizenship is accepted by both Governments and would not be affected by any future change in the status of Northern Ireland.

- The participants also note that the two Governments have accordingly undertaken in the context of this comprehensive political agreement, to propose and support changes in, respectively, the Constitution of Ireland and in British legislation relating to the constitutional status of Northern Ireland.

The GFA created new institutions and related bodies across three strands whose implementation has been the basis for peace building in Northern Ireland. Strands Two and Three established strong cross-border cooperation.

- Strand one – the internal Northern Ireland dimension: the Agreement created a new devolved assembly (Stormont) and executive for Northern Ireland, with a requirement that the executive power had to be shared by parties representing the two communities, so that both communities would be fairly represented in political debates and Northern Ireland would be governed by cross-community consent.

- Strand Two – the North-South dimension: a North-South Ministerial Council was established, institutionalising the link between the two parts of Ireland “to bring together those with executive responsibilities in Northern Ireland and the Irish Government, to develop consultation, co-operation and action within the island of Ireland – including through implementation on an all-island and cross-border basis – on matters of mutual interest within the competence of the Administrations, North and South.”

The agreement stated that:

The areas for North-South co-operation and implementation may include the following:

- Strand Three – the East-West dimension: a Council of the Isles was created, recognising the “totality of relationships” within the British Isles, including representatives of the two governments, and the devolved institutions in Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland.

The agreement stated that:

- A British-Irish Council (BIC) will be established under a new British-Irish Agreement to promote the harmonious and mutually beneficial development of the totality of relationships among the peoples of these islands.

- Membership of the BIC will comprise representatives of the British and Irish Governments, devolved institutions in Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales, when established, and, if appropriate, elsewhere in the United Kingdom, together with representatives of the Isle of Man and the Channel Islands.

- The BIC will meet in different formats: at summit level, twice per year; in specific sectoral formats on a regular basis, with each side represented by the appropriate Minister; in an appropriate format to consider cross-sectoral matters.

- Representatives of members will operate in accordance with whatever procedures for democratic authority and accountability are in force in their respective elected institutions.

- The BIC will exchange information, discuss, consult and use best endeavours to reach agreement on co-operation on matters of mutual interest within the competence of the relevant Administrations. Suitable issues for early discussion in the BIC could include transport links, agricultural issues, environmental issues, cultural issues, health issues, education issues and approaches to EU issues. Suitable arrangements to be made for practical co-operation on agreed policies.

On the British side, the British-Irish Agreement replaced the Government of Ireland Act of 1920. In Ireland, the government committed to amending Articles 2 and 3 of the Republic’s Constitution to reflect an aspiration to Irish unity through purely democratic means. Article 3 implicitly recognises that Northern Ireland is a part of the United Kingdom’s sovereign territory – the Republic of Ireland renounced its long-standing territorial claim over Northern Ireland (which was therefore removed from the Irish constitution). From a unionist point of view, it became then acceptable for the border to be a soft one, as it became less contested and Ireland’s territorial claim over Northern Ireland was no longer a threat to the unity of the UK.

3.2 Immigration and the free circulation of Irish and British citizens

Today, officials from Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland seem to agree on the fact that there are 208 border crossings along the 500-kilometre-long border [10]. It is safe to say that the first officially agreed count since the island was partitioned and the mapping out of the crossings were not easy tasks to carry out. However, the question is not so much that of the return of a border, which seems both essential and inevitable (all the more so if the United Kingdom leaves the European Union without agreement) but that of the type of border and the range of the possible solutions to control the movement of people (including EU nationals) and apply future customs regulations and taxes (the UK must eventually leave the single market and the customs union) on the flow of goods between the European and British territories since the European Union and the United Kingdom have repeatedly reiterated their commitment not to re-establish a "hard border", that is a border with inspection posts and guards.

Insert 5 – What is a hard border?

The phrase ‘hard border’ covers an enormously wide spectrum. At one end we have what a layman might naturally assume it to mean: a clearly visible national frontier, protected by border guards and equipped with customs posts. None of the negotiating parties has expressed any desire to introduce such a border between Northern Ireland and Ireland.

At the other end of the spectrum, and somewhat less intuitively, the phrase might not even be referring to a physical border at all. According to this interpretation, there could still be a hard border even if it is invisible and frictionless on the ground, i.e. a frontier with no physical infrastructure, no checks or controls of any kind and imposing no delay on the transit of goods and persons. This view was expressed by Queen’s University Belfast sociology lecturer and border specialist, Katy Hayward, in evidence before the same parliamentary committee in October 2017: “The question of physical infrastructure is a bit of a distraction. It does not mean that we do not have a hard border. Because those rules will be different in Northern Ireland, if the UK as a whole, including Northern Ireland, leaves the single market and the customs union, we will have a hard border.” [11]

Defining a hard border

The terminology is important because a hard border has been associated with the prospect of new border infrastructure, which could be reminiscent of the security installations erected during the Troubles. Following the referendum result, the Prime Minister gave assurance that there would be no return to “the borders of the past”. This commitment has since evolved into a guarantee that there will be “no physical infrastructure at the border”. Robin Walker, Parliamentary Under Secretary of State at the Department for Exiting the European Union, described a hard border as one “where people are stopped and where there is physical infrastructure that gets in the way of everyday lives.” The EU has also stated the aim of avoiding “physical border infrastructure”. Michel Barnier, the EU’s Chief Negotiator, declined to define a hard border when giving evidence to the Committee.

Characterisation of the land border as either hard or soft has been criticised because it presents a binary choice, rather than acknowledging the existence of a continuum of different options. Borders mark a physical area of territory and the legal space it encloses. They delineate the jurisdiction to regulate movement of persons, goods, services and capital within that legal space. Different rules apply to each of these aspects and so, in legal terms, there is not just one border, but many. Katy Hayward [...] explained the importance of differentiating between separate aspects of the border:

“You can have a soft border for travel, through the Common Travel Area, at the same time as having a hard border for customs. For example, the Common Travel Area continued even when the Anglo-Irish trade war was going on. At the same time of course you can have a hard border, as we had for travel through the military checkpoints at the land border, and a softer border for customs, as came about with the creation of the Single Market in 1993.”

Source: https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201719/cmselect/cmniaf/329/32904.htm#_idTextAnchor027

The critical question is therefore about the technological possibilities (assuming that the political issues are solved) which would enable the United Kingdom and the European Union to enforce inevitable customs checks, whether for people or for goods, while keeping the appearance of a completely open border, a “frictionless and seamless border”, without any physical infrastructure and border guards. The question can be asked differently, but remains straightforward: what are the technological solutions which allow a hard border to be invisible? Put differently, is a “smart border” an appropriate solution in the case of the Irish border?

The reinstatement of a border between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland obviously raises the question of the circulation of people. It is a fact that crossing the border is daily routine for many Irish and Northern Irish people. Movements of people between Northern Ireland and Great Britain/ Ireland are extensive, which makes the question a very tricky one. People make journeys for a wide variety of reasons including work and business, studies, shopping, tourism, medical treatment, visits to friends and family, for an estimated 110 million person crossings and 72 million vehicle crossings per annum. It is not unusual for many local people living in the cross-border region to cross the border several times a day. There is no doubt that the return of border checks would be a major inconvenience for those people with regard to the practicalities of their everyday lives. It is therefore not an option, even if the example of the French-Swiss border shows that it is possible to keep a border open for commuters (the traumatic aspect of the return of physical infrastructures at the border should not be underestimated in the Irish context though). On top of that, East-West crossings across the Irish Sea account for an estimated 23 million people and 3.1 million vehicles per annum [12].

Taking back control onto European migration into the UK was one of the leading Brexiters’ promises and remains one of the British government’s top priorities. But the British government is mired in a very uncomfortable position. On the one hand, it is politically unacceptable to allow the free circulation of people through the Irish border, which would mean that the British government would not deliver on its promise to control EU immigration – Ireland could be seen by EU migrants as a backdoor to the UK. On the other hand, however, it is equally politically unacceptable to reinstate a border with checks. Both unionists and nationalists strongly oppose it, for it would stand against the Good Friday Agreement provisions and be a serious obstacle in local people’s everyday lives.

In addition, the reinstatement of a border raises the question of the freedom of movement for British and Irish citizens who currently benefit from the Common Travel Agreement (CTA) – neither the UK nor Ireland are members of the Schengen Area. The CTA has been in place in various forms since the partition of Ireland and regulates travel between Ireland, the UK, the Channel Islands, and the Isle of Man. Irish and British citizens are able to move freely, settle, work and vote and have access to welfare within the CTA zone, which involves close coordination between the Irish and UK authorities. The current provisions of the CTA are protected by article 5 of the protocol on Ireland and Northern Ireland.

3.3 Economic stakes on each side of the border

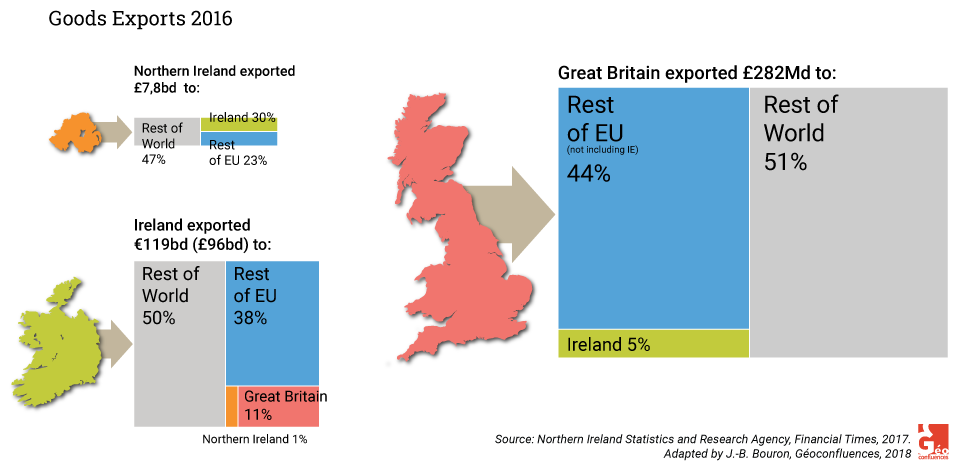

There is a substantial amount of economic and trade exchanges between the UK/ Northern Ireland and Ireland. They are facilitated by the invisible/ soft border.

Great-Britain is Northern Ireland’s main economic partner. In 2016, Northern Ireland’s sales to GB were worth 1.3 times more than all exports (Ireland, rest of EU, rest of the world combined) and 3.7 times more than its exports to Ireland. Northern Ireland’s sales to Great-Britain were worth £14.6bn in 2016, that is 56.2% of its external sales and 19.2% of its total sales. However, Ireland remains Northern Ireland’s single largest export market worth £4.0bn in 2016, amounting for 35% of its exports, and 15.4% of its external sales (5.3% of its total sales).

A close look at export of goods to Ireland shows that it was worth £2.4bn in 2016 and that the largest export sector was food and live animals, representing 31% of total exports. The second sector was machinery and transport equipment (17%) and the third sector was manufactured goods (16%). The three sectors combined make up 64% of all exports from Northern Ireland to Ireland in 2016, worth £1.5bn [13].

Figure 7. Exportations from and between Ireland, Northern Ireland and Great-Britain, and to the EU and the rest of the world

On the other side, the Republic of Ireland is the fifth biggest customer for UK exports and the UK is the second biggest customer for Irish exports. The UK represented 13.8% of Ireland’s total goods exports in 2015 and it represented 25.7% of Ireland’s total goods imports. Export of services to the UK from Ireland accounted for 17.7% of all services in 2014 (£17.98bn) and imports from the UK accounted for £11.4bn (10.4% of all import services) (see Brexit: Ireland and the UK in Numbers, p.43).

On the other side, the Republic of Ireland is the fifth biggest customer for UK exports and the UK is the second biggest customer for Irish exports. The UK represented 13.8% of Ireland’s total goods exports in 2015 and it represented 25.7% of Ireland’s total goods imports. Export of services to the UK from Ireland accounted for 17.7% of all services in 2014 (£17.98bn) and imports from the UK accounted for £11.4bn (10.4% of all import services) (see Brexit: Ireland and the UK in Numbers, p.43).

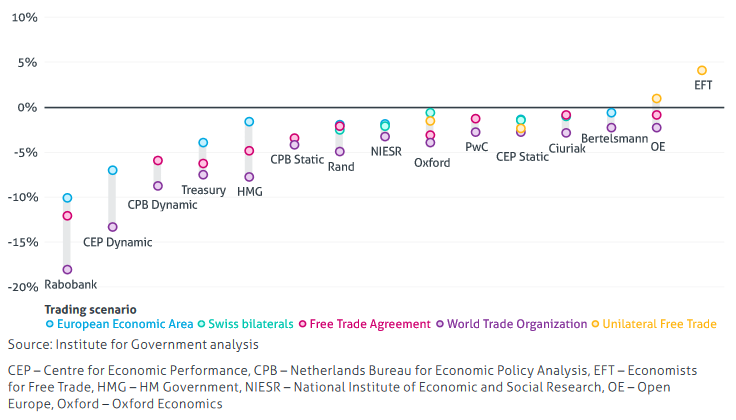

The economic consequences of Brexit are by definition difficult to predict. They will depend on the nature of the agreement reached by the United Kingdom and the European Union, if the two sides ever come to an agreement. We will then know the conditions of access of the United Kingdom to the single market and the cost of the possible reintroduction of customs taxes. In the meantime, it is impossible to predict with certainty the consequences of Brexit on Anglo-Irish trade relations, British and Irish GDP and the North Irish economy. However, Brexit is almost unanimously presented as a threat to the prosperity of the United Kingdom and Ireland. The differences in projections basically relate to the extent of the negative impact of Brexit. Many projections have been made, which have been summarised in a report from the think-tank Institute for Government. It rightly emphasises how difficult it is to make predictions (all the more so as several scenarios are to be taken into account), as well as the broad spectrum covered by these projections.

Figure 8. Forecast long-term impact of Brexit on GPD, relative to remaining in the EU

A very recent report from the British government shows that while the British economy will continue to grow in the long run, Brexit will have negative impacts, the extent of which will depend on the conditions of the withdrawal of the United Kingdom from the European Union. The results of the projections as seen in 15 years’ time vary considerably according to the variables used (in particular regarding changes in immigration rules) and the four scenarios considered (no-deal, free-trade agreement with the European Union, European Economic Area membership, soft Brexit based on the July 2018 White Paper provisions): no-deal appears to be the worst possible scenario for the British economy while soft Brexit would be the least damaging scenario for all British regions. Depending on the projections, Britain’s GDP is bound to decline within a very wide range of -0.6% to -9.3% compared to the current situation.

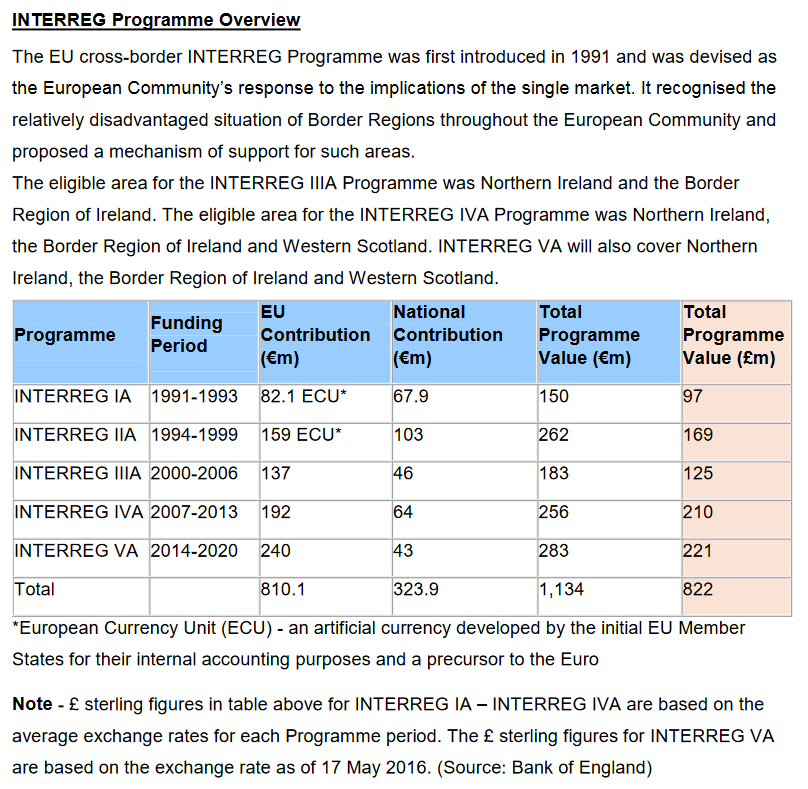

The report provides very little information about the economy of Northern Ireland. It simply states that the manufacturing sector would be particularly affected in the no-deal scenario and that Northern Ireland, Wales and Scotland would all see sizeable reductions in their level of economic output. Northern Ireland has the highest proportion of low-skilled men in British industries that are highly exposed to Brexit (in terms of the likely decline in output from that sector). It is expected that these workers may find it particularly difficult to find new jobs in their area in case they are made redundant. Northern Irish economy is expected to bear the brunt of Brexit, all the more so as it is fragile and lags behind the rest of the UK, relying heavily on public sector spending and European funds, in particular for agriculture [14]. Jobs and GPD in Northern Ireland are more dependent on agriculture and agri-food business than in any other British region. The impact of Brexit in that particular area will therefore be determined by the way Britain will financially compensate for the loss of European funds. The major role played by the various European funds for infrastructures and economic development should finally be pointed out in particular in the agro-food sector in Northern Ireland. The INTERREG programme has a strong cross-border dimension.

Insert 6 - What is the INTERREG VA programme?

The €283m INTERREG VA Programme is one of 60 similar funding programmes across the European Union that have been designed to help overcome the issues that arise from the existence of a border. These issues range from access to transport, health and social care services, environmental issues and enterprise development.

Since 1991 the INTERREG Programme has brought in approximately €1.13 billion into the region. This funding has been used to finance thousands of projects that support strategic cross-border co-operation in order to create a more prosperous and sustainable region. The new programming period for 2014-2020 provides opportunity for continued EU assistance to help create a more prosperous and sustainable cross-border region.

In total 85% of the Programme, representing €240m is provided through the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF). The remaining €43m, representing 15% is match-funded by the Irish Government and the Northern Ireland Executive. The content of the new INTERREG VA Programme has been agreed by the Northern Ireland Executive, the Irish Government, the Scottish Government and the European Commission. It has four core objectives where it will make a real and lasting change in terms of Research & Innovation for cross-border enterprise development; Environmental initiatives; Sustainable Transport projects; and Health & Social Care services on a cross-border basis.

Figure 9. The INTERREG Programme. Counties and funding

|

|

|

Les comtés irlandais, districts nord-irlandais et wards écossais concernés par Interreg VA. Source : https://www.seupb.eu/iva-overview

|

The reinstatement of customs checks and tariffs and taxes is likely to hamper trade flows and make them costlier. As a result, it is expected to harm the economy on both sides of the border. A report published by the Irish central bank forecasts a 9.6% contraction in trade between Ireland and the United Kingdom due to the increase in non-tariff barriers (norms and regulations, quotas, border checks, etc.) following the United Kingdom’s exit from the European Union. Beverages, fresh foods and raw materials would be the most exposed. Although it is thriving and has a positive outlook, Ireland’s economy is very likely to suffer from Brexit.

Insert 7 – The possible consequences of Brexit on the Irish economy

The Irish economy looks set to register another very strong year of growth in 2018, with the outlook remaining positive as well for 2019. While difficulties persist with the interpretation of the National Accounts, it is fair to say that the growth performance in 2018 has been broadly based with both domestic and external factors contributing significantly to the growth performance. Overall, while headline GDP suggests a growth rate of over 8 per cent for the economy, underlying economic activity grew somewhere in the region of 4.5 to 5 per cent. While the outlook for 2019 is also positive for the Irish economy, next year will see a number of significant challenges mainly from an international perspective. The outcome of the Brexit process is particularly important. A relatively benign UK exit such as the establishment of a European Economic Area agreement would see the Irish economy grow by 3 per cent in 2019, compared to a 4 per cent outcome where the UK remains in the EU. If the United Kingdom were to leave under a WTO style agreement, then Irish economic activity in 2019 would grow by just over 2.5 per cent in 2019.

Source: https://www.esri.ie/system/files/media/file-uploads/2018-12/QEC2018WIN.pdf, p. 1.

Conclusion

Northern Ireland is an exposed part of the UK: its vulnerability is likely to be exacerbated by the consequences of Brexit and the reinstatement of a border, whether it is physical or not and whatever its location. The Irish border issue has to be understood in the wider context of the crisis of the British identity and of the current constitutional arrangements of the four nations forming the British state. Northern Ireland can’t be treated as an exception by the British government for fear of having to deal with unionists’ wrath and Scotland’s independence.

As a peripheral area, Northern Ireland does not seem to be the object of sustained attention from London and its political divisions and weaknesses are undoubtedly a serious handicap to make its voice heard. Political fragmentation and ethno-national divisions make the defence of Northern Ireland’s interests far less effective than in Scotland. The British government’s White Paper published in July 2018 did not propose any practical solution to preserve the overall stability of Northern Ireland. Its one and only promise is not to reinstate a hard border, that is, in this particular case, considering the historical, political and social context, a border with guards and border inspection posts. The British government is very much eager, not to say desperate, to “protect the union, avoiding the need for any hard border between Northern Ireland and Ireland, preserving the constitutional and economic integrity of the UK, and meeting the needs of the wider UK family, including the Crown Dependencies and the Overseas Territories” (see The Future Relationship Between the United Kingdom and the European Union, juillet 2018, p.97). However, it is legally bound to organise the withdrawal of the United Kingdom from the European Union without the possibility of reinstating a hard land border with the latter. This is a terribly complex problem, whose solution has yet to be found.

Further Reading

Bibliography

AMILHAT SZARY, Anne-Laure. 2015. Qu’est-ce qu’une frontière aujourd’hui . Paris: PUF.

BIGAND, Karine. 2017. « L’Irlande du Nord : un territoire vulnérable face au Brexit », Recherches internationales, p. 65-81.

BIGAND, Karine. 2017. « Les Élections à l’Assemblée nord-irlandaise de 2016 et 2017 : contextes, résultats, perspectives », Revue Française de Civilisation Britannique, volumne 21, n°4.

DUCLOS, Nathalie. 2014. L’Écosse en quête d’indépendance ? Le référendum de 2014. Paris: PUPS.

GILLISSEN, Christophe. 2017. « L’Irlande et le Brexit : un avenir incertain », Questions internationales, n° 85-86, p. 136-141.

HUTCHINSON, Wesley. 2017. « La dimension irlandaise », Outre-Terre n° 49, p. 154-165.

PEYRONEL, Valérie. 2015. « Northern Ireland: Devolution as an Electoral Issue in the 2015 UK General Election », Revue française de civilisation britannique, volume 20, n°3.

BERBERI, Carine. 2017. « Northern Ireland: Is Brexit a Threat to the Peace Process and the Soft Irish Border? », Revue française de civilisation britannique, volume 22, n°2.

Webography

- Analysis of the possible scenarios for the post-Brexit Irish border, by Political Sociologist of Queen’s University Belfast Katy Hayward.

- The Brexit Border in 4 key slides. Dr Katy Hayward gives an outline of what border controls could mean for different types of border with the EU after Brexit.

Complete Webography

About changing demographics in Northern Ireland

- https://www.irishcentral.com/news/irishvoice/why-can-unionists-not-see-a-united-ireland-is-inevitable

- https://www.irishcentral.com/news/thenorth/shock-as-expert-predicts-catholic-majority-in-northern-ireland-by-2021

- http://www.ninis2.nisra.gov.uk/InteractiveMaps/Population/Population%20Change/Population%20Estimates%20Broad%20Age%20Bands/atlas.html

For detailed figures about religion in Northern Ireland

To check the results by place name or postcode

- https://www.theguardian.com/politics/ng-interactive/2016/jun/23/eu-referendum-live-results-and-analysis or https://www.bbc.com/news/politics/eu_referendum/results

- EU referendum – The results in maps and charts: https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-politics-36616028

For a detailed analysis of Brexit results, see Mark Bailoni’s article:

Other resources on Géoconfluence

- http://geoconfluences.ens-lyon.fr/actualites/veille/brexit-cartes-infographies-analyses-sur-le-vote-du-23-juin

- http://geoconfluences.ens-lyon.fr/glossaire/brexit

Other resources on La Clé des langues

- https://cle.ens-lyon.fr/anglais/civilisation/domaine-britannique/le-royaume-uni-et-leurope/comprendre-le-brexit-

- https://cle.ens-lyon.fr/anglais/civilisation/domaine-britannique/le-royaume-uni-et-leurope/questions-d-actualite-brexit-analyses-et-interrogations-post-referendum

- https://cle.ens-lyon.fr/anglais/civilisation/domaine-britannique/le-royaume-uni-et-leurope/ou-est-la-crise-en-europe-

Watchtowers at the Irish border during the Troubles

A historical perspective on border crossings

For a complete analysis on the Good Friday Agreement, Brexit and rights in Northern Ireland, read Prof. McCrudden’s briefing: https://www.britac.ac.uk/sites/default/files/TheGoodFridayAgreementBrexitandRights.pdf

Good Friday Agreement

- https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2018/04/good-friday-agreement-20th-anniversary/557393/

- https://www.bbc.co.uk/newsround/14118775

- http://www.thejournal.ie/good-friday-agreement-what-is-it-3928739-Mar2018/

- https://www.historyextra.com/period/20th-century/a-brief-history-summary-of-the-good-friday-agreement/

- https://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/politics/good-friday-agreement-what-is-it-northern-ireland-belfast-1998-sinn-fein-the-troubles-a8278156.html

The Legacy of the Troubles

- Borderland: https://info.arte.tv/fr/borderland

- https://info.arte.tv/fr/en-irlande-du-nord-la-reconciliation-populaire-avance

- https://www.arte.tv/fr/videos/081327-016-A/20-ans-de-paix-en-irlande-du-nord-les-plaies-sont-elles-cicatrisees/

- https://www.arte.tv/fr/videos/081406-000-A/les-zones-d-ombre-du-conflit-nord-irlandais/

- https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2018/may/02/john-duncan-best-photograph-belfast-sectarian-divide-wall-northern-ireland

- https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2015/sep/29/belfast-berlin-wall-moment-permanent-peace-walls

- http://healingthroughremembering.org/

- http://www.slate.fr/story/161886/irlande-du-nord-mere-fils-tirer-dessus-ira#xtor=RSS-2

- CAIN Web Service - Conflict and Politics in Northern Ireland: http://cain.ulst.ac.uk/index.html

Border Crossings

- https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-politics-40949424

- https://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/photography/brexit-photos-irish-border-ireland-good-friday-agreement-life-northern-republic-a8296151.html

- https://info.arte.tv/fr/irlande-vers-un-retour-des-controles-la-frontiere

- Northern Ireland Affairs Committee – The land border between Northern Ireland and Ireland: https://www.parliament.uk/business/committees/committees-a-z/commons-select/northern-ireland-affairs-committee/inquiries/parliament-2017/future-of-the-irish-land-border-17-19/

- Dr Katy Hayward’s written statement on the Irish border: http://data.parliament.uk/writtenevidence/committeeevidence.svc/evidencedocument/northern-ireland-affairs-committee/the-land-border-between-northern-ireland-and-ireland/written/79307.html

- Mary C. Murphy’s blog: https://www.centreonconstitutionalchange.ac.uk/about/people/mary-c-murphy

- Frictionless borders. Learning from Norway: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/technology-41412561

- ‘Technology’ cannot make a hard border in Ireland soft : https://www.independent.co.uk/voices/irish-hard-border-soft-brexit-technology-theresa-may-a8242461.html

- https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2018/may/04/irish-border-backup-plan-suggests-checks-ports-airports-brexit

- https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2017/jun/21/how-does-the-irish-border-affect-the-brexit-talks

- http://theconversation.com/q-a-whats-going-on-with-brexit-and-the-irish-border-88520

- http://www.europeanfutures.ed.ac.uk/article-3093

- https://www.nytimes.com/2018/02/28/world/europe/uk-northern-ireland-brexit.html

Briefings of the British Academy

- https://www.britac.ac.uk/brexit-briefings

- https://www.britac.ac.uk/tag/brexit

- https://www.britac.ac.uk/sites/default/files/BAR31-07-Fuchs.pdf

Contributions from academics in support of Brexit

- https://briefingsforbrexit.com/what-on-earth-is-a-hard-border-by-martin-davison/

- https://briefingsforbrexit.com/eu-demands-violate-northern-ireland-human-rights/

- https://briefingsforbrexit.com/brexit-and-the-irish-border/

- Magazine for Northern Ireland’s business leaders and policy makers: https://www.agendani.com/

Other Resources

- https://fullfact.org/europe/eu-referendum-and-irish-border/

- https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-northern-ireland-43576458

- https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-northern-ireland-politics-44615404

- The hardest border: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/resources/idt-sh/The_hardest_border

- A personal statement about the border: https://www.flickr.com/photos/tiocfaidh_ar_la_1916/37557068136

Videos

- Brexit and the Irish Border Problem: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=napewyY5YVE

- Could Brexit lead way to a united Ireland?: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pXXIGxJTnpM

Euronews

- Is Ireland headed for trouble at the border?: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LB1FY7Q1pgQ

- The Irish border Brexit dilemma: http://www.euronews.com/2018/06/27/the-irish-border-brexit-dilemma

France 24

- What will happen to invisible Ireland-UK border after Brexit?: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8cDjT0r9IgM

- Future of Irish border still a thorny Brexit issue: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4C1CxYhafY8

- Border - Brexit and the Irish Border | Short Documentary: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HiY5kZewGgo

BBC Newsnight: BBC Newsnight Irish Border

- What would Brexit mean for the border between Ireland and NIreland?: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uvvtwMWdXd0

- How do we solve the Brexit border problem?: https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p0677d2b 15 May 2018

- Brexit, dissidents and the Irish border: https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p067cfdm 16 May 2018

- Brexit: ‘Stakes are high’ for Strabane: https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p067jh8f 18 May 2018

- Watch Mary C. Murphy’s conference: Europe and Northern Ireland’s Future: Negotiating Brexit’s Unique Case

Notes

[1] They are also called peripheral nations. The expression minority nations is used by Nathalie Duclos in L’Écosse en quête d’indépendance ? Le référendum de 2014, Paris, PUPS, 2014.

[2] See : BBC, The Telegraph, and The Independant.