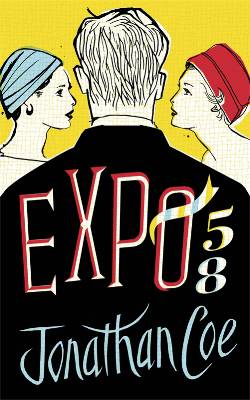

An interview with Jonathan Coe («Expo 58»)

interviewed by Clifford Armion,

14th February 2014, Hôtel Carlton, Lyon

Clifford Armion: I’d just like to ask you a few questions about the novel Expo 58 which is set in Brussels during the world’s fair of 1958. How did you come to get interested in that context of the world’s fair?

Jonathan Coe: I’ve been spending a little bit of time in Belgium, in the Flemish speaking part in fact. There’s a writer’s residence just outside Brussels, about thirty minutes by train. I was invited to stay there a few times, to write. I wrote most of my novel The Terrible Privacy Of Maxwell Sim while I was there. It’s a place called the Villa Hellebosch. Basically I found that you can’t spend any amount of time in Belgium without people telling you about expo 58. It still occupies a very large place in the collective national memory. So I was hearing stories about Expo 58 and I was also taken to visit the Atomium to do an interview there. Gradually everything about it started to fascinate me. It seemed so cutting-edge in terms of culture, design, architecture – the design of Expo 58 still looks modern and striking today. Plus for all these different countries including America and the Soviet Union to come together at this particular moment in history, just thirty years after the end of WWII, at the height of the Cold War, to put their pavilions side by side and to try to project rival images of their national character, to sell themselves to a global audience, that struck me as a really interesting theme or background. I believed putting a naïve, slightly unworldly Englishman into the middle of this extraordinary event would create something.

CA: The British pavilion is also central to the book and it’s supposed to represent Englishness. Do you think that it’s abroad that national characteristics are expressed in the clearest way?

JC: I think that’s very true. Periodically, we have these debates in the UK about what is Britishness, what is Englishness. When I was writing the book in 2012 we were putting on the Olympics and Danny Boyle did a magnificent Olympic opening ceremony which asked exactly those questions. It’s a topic that comes up occasionally in the UK but when I come abroad and talk to journalists in Belgium, France and Italy about my books, they always perceive these books as being very English. When I ask them what that means they’re never able to tell me. And when they ask me what I think it means I’m never able to tell them. There’s definitely something about Englishness and the English sense of humour which seems to fascinate our continental allies.

CA: There’s a sort of dramatic irony when you look back at the British society of the 1950’s, like when your protagonist Thomas Foley says that his wife is right to smoke during pregnancy because that’s the most stressful time in a woman’s life. Did you take pleasure in looking at those assumptions which look very remote, almost absurd to us now?

JC: I didn’t want to make fun of the 1950’s too much but I always allow myself to have a certain amount of fun with the conventions of whatever period I’m writing about. I did it with the 1970’s in Bienvenue au club. The book is a kind of satire on naivety or a comic celebration of idealism, whichever way you want to look at it, specifically in relation to science and technology because this is what the Atomium, which was at the centre of the expo site, represents for me. It’s a bold statement of faith in the power of science and technology to save us, to make our lives better. Now of course fifty years later we know that it’s not as simple as that. Science is our enemy as much as it is our friend. I thought the smoking thing was an interesting and funny example that people really did think that cigarettes were good for you because they helped you to relax and the studies proving links with lung cancer were just beginning to appear. As well as being a joke it seemed quite a plausible thing for people to say.

CA: Is it also a form of satire of the travel book? Your character sounds a bit like Gulliver in Gulliver’s Travels and he certainly is gullible as you said.

JC: That’s true. I hadn’t thought of the parallel with Gulliver before. Compared to the grey monochrome England that he leaves behind, the world of Expo 58 which Thomas lands in – finds himself shipwrecked in – is like something out of a fairy tale. Nothing there is real. Everybody is telling stories about themselves in one way or another, whether it’s people who are pretending to do one things in the pavilions but who turn out to be spies, or things like this kitsch version of old Belgium called La Belgique joyeuse – Gay Belgium – another thing I had a few jokes about…

A few words on Expo 58

As soon as he arrives at the site, Thomas feels that he has escaped a repressed, backward-looking country and fallen headlong into an era of modernity and optimism. He is equally bewitched by the surreal, gigantic Atomium, which stands at the heart of this brave new world, and by Anneke, the lovely Flemish hostess who meets him off his plane. But Thomas's new-found sense of freedom comes at a price: the Cold War is at its height, the mischievous Belgians have placed the American and Soviet pavilions right next to each other - and why is he being followed everywhere by two mysterious emissaries of the British Secret Service? Expo 58 may represent a glittering future, both for Europe and for Thomas himself, but he will soon be forced to decide where his public and private loyaties really lie.

Pour citer cette ressource :

Clifford Armion, Jonathan Coe, An interview with Jonathan Coe (Expo 58), La Clé des Langues [en ligne], Lyon, ENS de LYON/DGESCO (ISSN 2107-7029), février 2014. Consulté le 07/02/2026. URL: https://cle.ens-lyon.fr/anglais/litterature/litterature-britannique/an-interview-with-jonathan-coe-expo-58-

Activer le mode zen

Activer le mode zen