Mobility and Immobility in Colm Tóibín’s «Brooklyn»: Migration as a Static Initiatory Journey

Cet article a été rédigé dans le cadre d'un stage de Pré-Master à l'ENS de Lyon.

Introduction

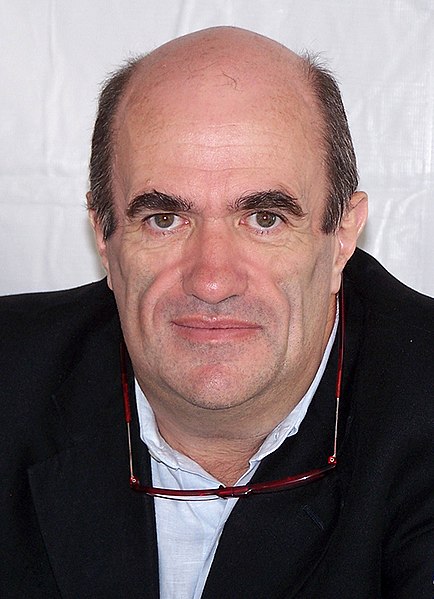

Colm Tóibín was born in 1955 in Enniscorthy, County Wexford, Ireland, and started writing poetry and stories at the age of twelve, soon after the death of his father. He graduated from University College Dublin and began a career in journalism after living in Barcelona for three years, where he taught English. He wrote nine novels: The South (1990), The Heather Blazing (1992), The Story of the Night (1996), The Blackwater Lightship (1999), The Master (2004) which won the Los Angeles Times Book Prize for fiction, Brooklyn (2009) which won the Costa Fiction Award, The Testament of Mary (2012), Nora Webster (2014), and House of Names (2017). He also wrote two collections of short stories: Mothers and Sons (2006) and The Empty Family (2010).

Brooklyn, a four-part novel published in 2009, focuses on Eilis Lacey who lives with her mother and older sister Rose in the town of Enniscorthy, County Wexford, where she studies bookkeeping and works in Miss Kelly’s shop. Thanks to her sister and an emigrant priest called Father Flood, Eilis is offered a place and a job in Brooklyn, New York. Once in America, she adapts to her new life in Mrs. Kehoe’s Irish boarding house, in the shop where she works, Bartocci’s, and in Brooklyn College where she takes classes in accountancy. She meets an Italian-American man, Tony, at a dance organised by the Irish parish. Before her return to Enniscorthy to pay her respects to her sister who has died of heart failure, Tony convinces her to marry him. Back in Ireland, her community notices her new American style, and she lets Jim Farrell, a good match, court her. Feeling threatened by Miss Kelly’s acquaintance with Mrs Kehoe and the possibility that they might hear of her ‘double life’, Eilis must leave once again for America.

In Brooklyn, Colm Tóibín focuses mostly on the experience of migration and the conflict between duty and freedom. Indeed, the novel explores the tensions between the individual and the requirements of family life as Eilis struggles between three families: her family in Ireland, the one she will start with Tony, and the family she could have had with Jim Farrell. This article will be centred on the theme of migration around which Brooklyn is built, as it tells the story and hardships of an Irish female emigrant. Migration as an individual experience interrogates the migrant’s relationship to his or her nation, and the nation he or she migrates to. It can be associated with the idea of an initiatory journey, in the sense that experiencing two countries or cultures changes and shapes one’s identity. Migration differs from the notion of exile, which relates to migrants who are banished from their homelands and become outsiders in their home-state – that is, the country they settle in. In Colm Tóibín’s Brooklyn, Eilis Lacey’s experience of migration and of identity construction is linked to both mobility and immobility. Eilis is mobile because she moves from one country to another and seeks economic and social autonomy. However, she is also confronted to immobility as she is trapped between two ‘homes’ and two identities, one Irish, the other North-American. This article aims to show that the protagonist’s migration in Brooklyn is paradoxically mainly static, in terms of both space and identity. First, the novel is inscribed within the Irish literary and historical tradition of migration to America: Eilis Lacey is a migrant whose life and identity are shaken and transformed through her interactions with another country and with other people. However, her migration from Ireland to America cannot be completely considered as mobility, for Eilis eventually equates the two places as one and the same. Eilis’s experience of mobility can therefore be considered as a partial initiatory journey, because she can never fully fix her own identity, which remains incomplete, torn between two selves.

1. Eilis Lacey and Irish migration

1.1 Ireland, contemporary Irish fiction and migration

The Republic of Ireland and Irish literature have a specific relationship with migration. Irish people have emigrated from their country since the eighteenth century, although the peak of Irish migration was reached in the middle of the nineteenth century, during the Great Famine, leading millions to move out of Ireland, notably to North America. Although migration is omnipresent in Irish history, literary narratives about mobility were scarce until the second half of the twentieth century. Indeed, migration and exile became major themes of contemporary Irish fiction (O'Brien in Harte and Parker, 2000, 35), enabling writers to give a voice to the past and reclaim part of the history of Ireland.

Brooklyn is inscribed within this contemporary trend of migration in Irish fiction and represents migration as it was experienced in the Ireland of the 1950s. At the time, leaving Ireland was an act one did not speak of, which explains the late apparition of the theme in Irish fiction, as it was a “dual negative in Irish life, its combination of depletion and silence making it doubly difficult to represent” (Harte in Harte and Parker, 2000, 52). The shame that surrounds migration is reflected in Tóibín’s novel by the fact that Eilis and her family barely mention her three brothers who emigrated to Birmingham, especially Jack: “She would have loved to say something about him [Jack], but she knew that it would make her mother too sad. Even when a letter came from him it was passed around in silence” (Tóibín, 2010, 15).

In Brooklyn, Tóibín represents the historical reality of migration through literature. First, he pays tribute to the migrants of the Great Famine, by equating the conditions of Eilis’s trip to America to the Irish migrants’ in the mid-nineteenth century. To Eilis, as to her predecessors, the week-long stormy journey “is hell” (Tóibín, 2010, 38), as her travel companion Georgina puts it. Then, the novel stages characters that represent the archetypical figures of migration. For instance, Father Floodbrings to mind the emigrant advice agents who tried to encourage potential workforce to migrate by praising the opportunities abroad. In the same way, Georgina might stand for the experienced migrant, who is used to travelling back and forth to her homeland and assists Eilis in her first trip.

1.2 The emigration of women as a means for their emancipation

More specifically, Brooklyn provides an insight into the historical reality of Irish female emigrants, through Eilis Lacey’s perspective. It was only from the 1990s that Irish fiction started to picture the migration of women, who were historically more numerous than Irish male emigrants between 1871 and 1971 (McWilliams, 2013, 24). Nonetheless, they were not widely represented in literature because their mobility contradicted the ideal which the newly independent Irish State projected on them at the beginning of the twentieth century. Irishwomen were associated with home – understood both as ‘the house’ and ‘the motherland’ – while Irishmen were required to emigrate for economic purposes. According to Breda Gray, women have emigrated from Ireland for a variety of motives:

Women have left Ireland in search of life opportunities, sexual liberation and career advancement, to give birth and to have abortions, as a means of personal survival and of contributing to the survival of their families in Ireland. They have emigrated to escape difficult family circumstances, heterosexism, Catholicism and the intense familiarities and surveillances that have marked Irish society. […] They have left voluntarily and involuntarily, by chance and because others were leaving. (cited in McWilliams, 2013, 24)

In Tóibín’s novel, Eilis initially migrates “involuntarily” for economic reasons (for the “survival” of her family in Ireland), just like her brothers. However, her migration eventually becomes the vector of her emancipation, as it did for many Irishwomen at the time. In the United States of America, Eilis finds “life opportunities, sexual liberation and career advancement”, as Gray puts it. First, she progressively grows financially independent thanks to her job at Bartocci’s, and she intends to become an accountant by taking classes at Brooklyn College. Indeed, she tells Father Flood that her contemplated career will allow her to repay him for the money he lent her: “‘I have saved some money,’ Eilis said, ‘and will be able to pay my tuition the second year and then pay you back for last year when I get a job.’” (Tóibín, 2010, 152) Then, Eilis embraces autonomy in her sexuality, confronting the “surveillances that have marked Irish society”: in America, she meets her future husband, Tony, with whom she explores her sexuality by having premarital sex under the roof of Mrs. Kehoe, Eilis’s Irish stern landlord.

However, Eilis’s emancipation remains restricted. In the 1950s, women were still largely confined to a domestic life and subservient to men and this was also the case in North America. In Brooklyn, even though she becomes more and more self-reliant, Eilis has little ambition for herself, and mainly pictures herself as a housewife:

She knew that once she and Tony were married she would stay at home, cleaning the house and preparing food and shopping and then having children and looking after them as well. She had never mentioned to Tony that she would like to keep working, even if just part time, maybe doing the accounts from home for someone who needed a bookkeeper. (Tóibín, 2010, 213)

Thus, Eilis does have dreams and career prospects, yet she is conscious that, as a woman, her opportunities are limited, even away from home and family duties or Irish traditions.

1.3 An illusory opposition between Ireland and America

Before migrating, Eilis perceives her Irish homeland and her future North American home-state as antithetic, because she associates the former with her family’s expectations and the latter with freedom. Nevertheless, her binary vision, which will be contradicted by her actual experience of North America, is a product of her idealisation, and of the influence of the ‘American Dream’ that every migrant seeks.

Eilis sees her homeland, Ireland, as an obsolete and traditional society. In Enniscorthy, she works for Miss Kelly, an elderly woman who runs a grocery shop. To Eilis, Miss Kelly incarnates Ireland as an archaic and hierarchical system, as opposed to America’s equalitarianism. Indeed, the shop owner treats her customers differently, depending on their social status:

As each customer came into the shop on the days when she was being trained, Eilis noticed that Miss Kelly had a different tone. Sometimes she said nothing at all […]. For others she smiled drily and studied them with grim forbearance, taking the money as though offering an immense favour. And then there were customers whom she greeted warmly and by name; many of these had accounts with her and thus no cash changed hands, but amounts were noted in a ledger, with inquiries about health and comments on the weather [...]. (Tóibín, 2010, 9-10)

Ireland is further associated with tradition so that Eilis considers her existenceas already defined, and modelled on the life all Irish people are destined to: “Until now, Eilis had always presumed that she would live in the town all her life, as her mother had done [...]. She had expected that she would find a job in the town, and then marry someone and give up the job and have children.” (Tóibín, 2010, 27)

On the contrary, Eilis imagines her future home-state, America, as the place of desire and modernity. Before moving from Ireland, Eilis had assimilated commonplaces about life in America, which were so encrusted in her mind that she had come to believe them:

She had a sense too, she did not know from where, that [...] people who went to America could become rich. She tried to work out how she had come to believe also that [...] no one who went to America missed home. Instead, they were happy there and proud. She wondered if that could be true. (Tóibín, 2010, 24)

Her conception of the American Dream, which is shared by all migrants, is reinforced by Father Fell who promotes America as a land of opportunities: “‘In Brooklyn, where my parish is, there would be office for someone who was hard-working and educated and honest.’” (Tóibín, 2010, 22)

Eilis achieves the American Dream in Brooklyn through consumerism: she marries Tony with whom she will live on a piece of land he bought on Long Island, and is on her way to become an accountant. However, her dual conception of Ireland and America is questioned by her actual experience of migration: her mobility might not be true mobility, as her American experience mirrors her Irish one.

2. An immobile migration: Ireland and America as one place

2.1 Migration and the diasporic experience

Eilis is fundamentally ‘mobile’ in the sense that she moves to another space, Brooklyn, and that she undergoes an identity shift, from being subdued to progressively emancipated, from being exclusively Irish to being both Irish and American. Therefore, America seems to be a place of inclusion, open to a diversity of diasporic groups. In the introduction to Women and Exile in Contemporary Irish Fiction, Ellen McWilliams points out that the notion of ‘diaspora’ interrogates the relationship between a home nation and its communities living abroad (2013, 9). Brooklyn stages different diasporic groups in New York – that is, communities of migrants – among which the Irish community and the Italian one and Eilis is included in both. On the one hand, she develops a “diaspora consciousness” (McWilliams, 2013, 10) by exploring different Irish ‘territories’: first, the Republic of Ireland, then the Irish diasporic community of Birmingham where her three brothers live, and finally the Irish diasporic community in Brooklyn. As an Irishwoman, Eilis identifies with these diasporic spaces and with ‘Irishness’, in contrast to ‘Americanness’. On the other hand, Eilis also develops ties with other diasporic groups in America. She is courted by an Italian-American man and works in a shop that includes all American residents, regardless of their origins:

‘We treat everyone the same. We welcome every single person who comes into this store. They all have money to spend. We keep our prices low and our manners high. If people like it here, they’ll come back. You treat the customer like a new friend. Is that a deal?’ (Tóibín, 2010, 55)

Eilis’s experience of migration thus leads her to interact with different diasporic communities and to constitute her own identity as an Irish-American through their contact.

Nonetheless, America is also a place of exclusion that divides diasporic groups into defined communities and may prevent exchanges between them. When she moves from Ireland to Brooklyn, Eilis settles in an Irish parish, peopled by Irish migrants who mostly remain exclusive. In Brooklyn, some characters epitomise the rejection of other communities of migrants. Mrs. Kehoe’s prejudice against Italian people who “come looking for Irish girls” (Tóibín, 2010, 66) stands for the exclusion of non-Irish people from her own diasporic group. In the same way, Tony’s younger brother Frank states that he and his family “don’t like Irish people” (Tóibín, 2010, 148), which excludes Eilis from the Italian community. Thus, although America can appear as a place of mobility because migrants feel integrated there while keeping a link to their homeland, migrating to America can also be an experience of immobility that leads to a feeling of exclusion.

2.2 Ireland and America: two interchangeable countries

By settling in the Irish parish of Brooklyn, Eilis finds ‘Ireland’ in America. This contradicts her pre-migration conception of America as a place of freedom, for Irish traditions are what she is once again confronted to in her home-state. Father Flood himself describes Brooklyn as a ‘Little Ireland’ to Eilis: “‘Parts of Brooklyn,’ Father Flood replied, ‘are just like Ireland. They’re full of Irish.’” (Tóibín, 2010, 22) Brooklyn and Ireland can thus be considered as similar places, because the Irish traditionalism Eilis thought she would leave behind is omnipresent where she lives in Brooklyn, at Mrs. Kehoe’s boarding house. Indeed, the elderly Irish lady represents Irish authority and is in charge of the surveillance of the young Irish women she hosts, who have to follow her strict rules, such as not bringing any boy home, or only tackling decent subjects. In that sense, she becomes “the guardian of strict standards of female decency and the so-called ‘Irish manners’” (Carregal-Romero, 2018, 135) on the American land, just like Miss Kelly in Ireland. In Enniscorthy, Miss Kelly preserves morality by telling Eilis she knows she is married to Tony and discouraging her courtship with Jim Farrell. It is thus made impossible for Eilis to truly move away from a “transnational surveillance of Irish Catholic morality, personified here by Mrs Kehoe and Miss Kelly” (Carregal-Romero, 2018, 139), who happen to be cousins and maintain a link between America and Ireland.

If Ireland and America are similar because they are associated with the realm of the ‘known’ for Eilis – which is something that she may find reassuring about the Irish parish of Brooklyn – they are also comparable in the way they both gradually become unfamiliar they to her. It is paradoxically because Eilis’s sense of ‘home’ and belonging becomes flexible that her experience of migration can be considered as stationary – it did not bring her any sense of certainty about her identity. Firstly, Eilis can no longer see either country as her home. As Laura Elena Savu argues, Brooklyn “reconfigures ‘home’ from being a static, concrete place that grounds the immigrant’s identity to a constant negotiation of the boundaries between Ireland and America, past and present, public history and individual memory” (2013, 251). Because both Ireland and North America can mean home, Eilis is unable to choose between the two and is ultimately caught inbetween them, or rather ‘stuck’ – none is truly or fully home. Secondly, Eilis loses her sense of ‘spatial’ belonging – how close she feels to one space or country – as she loses her ties first with Ireland and then with America. Indeed, her two ‘homes’ become places of familiarity or unfamiliarity, depending on the country she is staying in: when she is in America, her homeland feels remote to her and when she visits her family in Ireland, her home-state feels distant. To Dilek Inan, “[m]uch of the novel is devoted to portray the power of the immediate place in which one lives” (cited in Stoddard, 2012, 102). When Eilis is in one country, she indeed pictures the other country as a ‘dream’, a place that is at the same time unfamiliar and unreal. When she comes back to Ireland, she feels that “not telling her mother or her friends [about Tony] made every day she had spent in America a sort of fantasy” (Tóibín, 2010, 211). Furthermore, she knows she will feel the same way about Ireland, once she is back in America: “she would look at them [her friends] and remember what would soon, she knew now, seem like a strange, hazy dream to her” (Tóibín, 2010, 246).

2.3 Eilis’s migration as a failed attempt to escape her fate and duty

Eilis’s mobility disrupts her identity more than it makes it clearer to her. Migrating to America tore her between two spaces, two worlds, between which she cannot choose. As argued before, she hoped to find freedom and to escape Irish traditionalism in Brooklyn. However, because North America reminds Eilis of Ireland, she finds in her home-state what she wanted to escape in her homeland, namely duty. To Eilis, Enniscorthy is associated with her family and filial responsibilities, because of the need to take care of her aging mother, especially after her older sister Rose died. In that context, going to America was the promise of independence. Nevertheless, Eilis’s fate is inevitable, as other obligations await her in America, namely her marital commitment to Tony, whom she marries before leaving for Ireland. She is thus divided between her husband and her family and feels “as though she were two people, one who had battled against two cold winters and hard days in Brooklyn and had fallen in love there, and the other who was her mother’s daughter” (Tóibín, 2010, 211). Therefore, Eilis’s migration can be perceived as immobile, because her life in America eventually mirrors the dutiful life she would have had in Ireland: “In Enniscorthy, the prospect of emigration presents itself as a rupture in her life’s expectations […]. However, when she returns to Enniscorthy, she has fulfilled precisely the destiny she thought she would escape by emigrating” (Moynihan, 2016, 98).

Eilis finds imperatives wherever she goes and whenever she tries to avoid them, they catch up with her. Indeed, she attempts to escape her marital engagement to Tony once back in Ireland by metaphorically forgetting about himand not reading the letters he sent her. As seen in the screenshot below (Crowley, 2015, 1"26'23), the film adaptation shows Eilis concealing Tony’s letters in a drawer, thus representing her attempt to escape her American duty by denying Tony’s very existence.

However, by trying to forget Tony and allowing Jim Farrell to woo her, Eilis almost engages in bigamy and flirts with immorality.

Her mobility can be considered as a ‘circle’, as she migrates back and forth between her two countries, somehow always fleeing herself rather than looking for her self. The restlessness of Eilis’s travelling is paradoxically static because it leads her nowhere, or at least not where she expects. As Shaun O’Connell maintains, Eilis’s moving about is motivated by both freedom and her quest for identity, and only ends with confusion and resignation:

For Colm Tóibín, being Irish means never being content with where you are, home or away. Eilis Lacey moves from Enniscorthy to Brooklyn, back to Enniscorthy, back to Brooklyn, all in search of who she can become and where she belongs, finally finding herself nowhere. In the process her Irish town moves in her mind from a place of confinement to a lost paradise; her America moves from a land of individual opportunity to a place of confinement as she keeps the vows and takes up the marital obligations she hoped to escape during her brief return to Ireland. Eilis cannot go home again. (2013, 10)

Eilis eventually perceives her homeland and home-state as alien, or as dreams. Eilis’s spatial immobility – the fact that to her, Ireland and America are equal – is mirrored by an inner immobility, as the protagonist does not entirely achieve her identity construction through her experience of mobility.

3. Eilis’s migration as an incomplete initiatory journey

3.1 Eilis’s duality: one body, two selves and spaces

Migrating is an opportunity for Eilis to become someone else than who she is expected to be in Ireland. She does change by going to America: she undergoes a complex identity shift throughout her journey, which can be understood as ‘initiatory’. Upon arriving in Brooklyn, Eilis still feels exclusively Irish and considers herself as an alien in America, which is evidenced by her homesickness: “She was nobody here. It was not just that she had no friends and family; it was rather that she was a ghost in this room, in the streets on the way to work, on the shop floor. Nothing meant anything. […] Nothing here was part of her. It was false, empty, she thought.” (Tóibín, 2010, 62) Nevertheless, she evolves from remaining Irish to living an Irish-American life, through a process of Americanization. Although she resides in an Irish parish of Brooklyn, Eilis becomes closer to the American space and way of life: she studies at Brooklyn College, visits Coney Island and goes to the cinema and baseball matches. As a result, she looks Americanized to her friends back in Ireland, who cannot help but notice her “new American figure” (Tóibín, 2010, 206).

However, Eilis’s identity transformation is incomplete because she is divided between two cultures, almost literally: she has a “double self” (Kovács cited in Raghinaru, 2018, 50). Even though she has adapted to America and her identity has changed under the influence of her home-state, Eilis’s diaspora consciousness makes it impossible for her to fully identify as Irish, because she lives in America, or as American, because she also feels Irish. This feeling is reminiscent of the complex ties migrants have with their homeland and home-state, according to Bronwen Walter:

Instead of a linear journey of migration from ‘outside’ to permanent settlement ‘inside’, accompanied by assimilation from identities of origin to those of destination, this notion of diaspora expects the two forms of consciousness to be held at the same time. The concept thus explicitly dislodges many kinds of binary notions: of migrant/settler, insider/outsider, home/away. In place of either/or relationships conventionally associated with the resettlement process, migrants and their descendants are connected by both/and ties to their countries of origin and settlement. (cited in McWilliams 2013, 15)

As a matter of fact, the protagonist’s name is reminiscent of her two homes and identities: ‘Eilis’ is close to ‘Eire’, which designates the Republic of Ireland, but it also resembles ‘Ellis Island’ ((Between 1892 and 1954, all immigrants arriving in North America had to be inspected on Ellis Island, an immigration station, before being allowed to settle in.)), the antechamber to the United States of America through which migrants were filtered. Therefore, everything in her self, even something as personal as her name, indicates that she is torn between the two countries, and that she cannot either define herself by one or embrace both. The night before her transatlantic journey, Eilis wishes she could split into two selves, one for each country, which is what will eventually happen: “The arrangements being made […] would be better if they were for someone else, she thought, someone like her, someone the same age and size, who maybe even looked the same as she did, as long as she […] could wake in this bed every morning” (Tóibín, 2010, 28-29). She thus lives in a form of spatial and identity ‘in-betweenness’. This duality shows that her migration is rather an exile, for she is always cut off from one country – the one she is not currently in – and from her self, and cannot fully grasp her identity, which is plural.

3.2 Eilis, a silent and passive character

Eilis’s inability to unite the part of her that is Irish with the American one traps her in a circle that partially excludes evolution. Before migrating, she was a silent and passive daughter, and when she comes back, her emancipated American self barely shows and she still has no voice or agency.

Before moving to Brooklyn, Eilis was indeed a character “without voice” (Young, 2014, 131), that is to say that she let others speak and decide for her without questioning their choice. She remained quiet when life-changing decisions were made for her, notably when her family organised her migration: “In the silence that had lingered, she realized, it had somehow been tacitly arranged that Eilis would go to America.” (Tóibín, 2010, 23) When Eilis comes back from Brooklyn, she is silent again, firstly because she cannot talk about her American experience and her new husband, and then because she becomes once again her mother’s dutiful daughter. Faced with Miss Kelly, who knows Eilis has a husband in Brooklyn and yet lets Jim Farrell court her, she does not defend herself and remains voiceless:

"Is that right, Miss Lacey? If that's what your name is now."

"What do you mean?"

"She [Mrs. Kehoe] told me the whole thing. The world, as the man says, is a very small place." […]

She stood up. "Is that all you have to say, Miss Kelly?" (Tóibín, 2010, 240)

Eilis lets Miss Kelly decide her fate for her; she is forced to go back to her husband in order to escape a scandal in Enniscorthy, were people to know she is already married. As Raghinaru argues, “Eilis pointedly does not have a voice. She is silent, and allows herself to be silenced, in a way that contravenes with the normative narratives of female empowerment in the private and public spheres” (2018, 47). Her quietness at key moments in her life thus contradicts the journey of liberation she undertook in Brooklyn, notably in terms of sexuality, as she is unable to be open about her relationship with Tony.

Tóibín’s style is representative of Eilis’s lack of agency. Indeed, it could be considered as ‘minimalist’, as the narrative focuses on Eilis’s thoughts while dialogues are scarce and mostly banal. Tóibín’s narrative choices thus mirror Eilis’s silence, as well as her indecision and passivity. Before going to America, Eilis was fundamentally inactive, in the sense that what happened to her was not initiated by her own actions, but rather by someone else’s: it was Father Flood who found her a room and a job in Brooklyn, Rose who called the American Embassy in Dublin to arrange her trip, and her brothers who paid for her fare. As a matter of fact, Eilis’s actions in Brooklyn are what Raghinaru calls “recessive action[s]”. This concept, theorised by Anne-Lise François in Open Secrets, refers to “the idea of ‘nothing’ as an event made or allowed to happen” (cited in Raghinaru, 2018, 45). Eilis lets things happen to her rather than makes them happen. She engages with recessive action again during her visit to Ireland, as “she thought it would be wise to make the best of it, take no big decisions in what would be an interlude” (Tóibín, 2010, 212). Her absence of “big decisions” leads to concrete and significant events such as her courtship with Jim Farrell.

3.3 The daughter of James Joyce’s “Eveline”

Eilis Lacey is reminiscent of a famous female protagonist in Irish literature: James Joyce’s Eveline. In 1904, Joyce published “Eveline” ((About James Joyce’s short story “Eveline”: https://interestingliterature.com/2017/07/a-summary-and-analysis-of-james-joyces-eveline/)), a short story that is part of Dubliners. Eveline is a young Irish girl who has the opportunity to leave Dublin on a ship to Argentina with her fiancé Frank, and yet chooses to stay home with her violent father, out of duty. Joyce’s short story may be compared to Tóibín’s novel as the two female protagonists share several characteristics: their names are “alike, with several shared letters” (Young, 2014, 124) and their fate is sealed by family duty – Eveline cannot migrate because she needs to take care of her father and Eilis has to migrate to financially sustain her family. Both characters are immobile and passive; indeed, Eveline is mainly silent, never speaks for herself, and can be said to engage in recessive action because her remaining in Dublin is a non-action that condemns her to a miserable life. Furthermore, Brooklyn pays tribute to James Joyce’s short story through an intertextual echo in the incipit. The novel opens on a scene where a passive Eilis sits at the window: “Eilis Lacey, sitting at the window of the upstairs living room in the house on Friary Street, noticed her sister walking briskly from work.” (Tóibín, 2010, 2) This actually echoes the first lines of “Eveline”: “She sat at the window watching the evening invade the avenue.” (Joyce, 1996, 37) Intertextuality in Brooklyn may aim at putting Eilis and Eveline on an equal footing and showing that little has changed between Eveline’s experience of (non-)migration and Eilis’s. Indeed, just like Eveline, Eilis is torn between duty and freedom, Ireland and elsewhere, and merely an observer of her own fate.

However, Tóibín’s Brooklyn also differs from Joyce’s “Eveline”, for Eilis does embark on a ship for the American continent. In that sense, as suggested by Tory Young, “Brooklyn tells the story of what would have happened if Eveline had left Dublin.” (2014, 126) Although she is forced to emigrate, Eilis does move to America and experiences life abroad, which enables her to engage in an initiatory journey, something Eveline does not. Because Tóibín’s protagonist has the opportunity to evolve and achieve the American Dream, she seems less paralysed than Joyce’s character.

Conclusion

Colm Tóibín therefore creates a paradoxically immobile emigration story: Eilis’s migration and initiatory process can be considered as static because instead of reconciling her two spatial and cultural identities, she loses her very sense of identity. John Crowley’s 2015 film adaptation of the novel contrasts with this analysis. While the film is mostly faithful to the plot of Brooklyn, Eilis’s characterisation and the ending differ from the novel. Indeed, the protagonist, played by Saoirse Ronan, progressively gains agency and ownership of her life. Unlike the novel, the film shows Eilis as a young woman who eventually manages to confront Miss Kelly and to assert her identity as Tony’s wife. The ending of the story also takes on a new meaning in the film: Eilis has become confident enough to decide her own fate and returns to Tony out of love, whereas her decision remains ambiguous in Tóibín’s version.

Notes

Bibliography

CARREGAL-ROMERO, José. 2018. ‘The Irish Female Migrant, Silence and Family Duty in Colm Tóibín’s Brooklyn’. Études Irlandaises, December.

CROWLEY, John. 2015. Brooklyn. Fox Searchlight Pictures, Wildgaze Films, BBC Films.

HARTE, L., and M. PARKER. 2000. Contemporary Irish Fiction: Themes, Tropes, Theories. 2000. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

JOYCE, James. 1996. Dubliners: Text and Criticism; Revised Edition. New York: Penguin Books.

MCWILLIAMS, Ellen. 2013. Women and Exile in Contemporary Irish Fiction. Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire; New York: Palgrave.

MOYNIHAN, S. B. 2016. ‘“We Are Where We Are”: Colm Tóibín’s Brooklyn, Mythologies of Return and the Post-Celtic Tiger Moment’.

O’CONNELL, Shaun. 2013. ‘Home and Away: Imagining Ireland Imagining America’. New England Journal of Public Policy 25.

RAGHINARU, Camelia. 2018. ‘Recessive Action in Colm Tóibín’s Brooklyn’. Text Matters: A Journal of Literature, Theory and Culture, no. 8 (October): 43–54.

SAVU, Laura Elena. 2013. ‘The Ties That Bind: A Portrait of the Irish Immigrant as a Young Woman in Colm Tóibín’s Brooklyn’. ResearchGate, Papers on Language and Literature (49): 250–72.

STODDARD, Eve Walsh. 2012. ‘Home and Belonging among Irish Migrants: Transnational versus Placed Identities in The Light of Evening and Brooklyn: A Novel’. Éire-Ireland 47 (1): 147–71.

TOIBIN, Colm. 2010. Brooklyn. New York: Scribner.

YOUNG, Tory. 2014. ‘Brooklyn as the “Untold Story” of “Eveline”: Reading Joyce and Tóibín with Ricoeur’. Journal of Modern Literature 37 (January): 123–40.

Adapting the ending of Brooklyn

At the end of Colm Tóibín’s novel, Eilis Lacey, who is visiting her family in Enniscorthy after the death of her sister Rose, learns that the local shop owner Miss Kelly knows from her cousin Mrs. Kehoe that Eilis married an American man. Eilis decides to go back to America on the first ship in order to avoid a public scandal relating to her relationship with Jim Farrell, to whom she writes a farewell note.

The ending of Colm Tóibín’s Brooklyn:

As the train moved south, following the line of the Slaney, she imagined Jim Farrell's mother coming upstairs with the morning post. Jim would find her note among bills and business letters. She imagined him opening it and wondering what he should do. And at some stage that morning, she thought, he would come to the house in Friary Street and her mother would answer the door and she would stand watching Jim Farrell with her shoulders back bravely and her jaw set hard and a look in her eyes that suggested both an inexpressible sorrow and whatever pride she could muster.

"She has gone back to Brooklyn," her mother would say. And, as the train rolled past Macmine Bridge on its way towards Wexford, Eilis imagined the years ahead, when these words would come to mean less and less to the man who heard them and would come to mean more and more to herself. She almost smiled at the thought of it, then closed her eyes and tried to imagine nothing more. (Tóibín, 2010, 246-47)

The ending of the film adaptation (2015):

In spite of the overall faithfulness with which Tóibín’s novel was adapted into a film, the two versions of the ending differ quite significantly. First, they do not focus on the same man. Tóibín’s Brooklyn ends on Eilis’s thoughts about her farewell to Jim, while the film adaptation focuses on Eilis and Tony’s romantic reunion in Brooklyn. Furthermore, the novel preserves a certain amount of ambiguity about Eilis’s feelings: the reader cannot know exactly if she is happy or resigned about her fate. The sentence “these words [...] would come to mean more and more to herself” can either suggest that she is glad to go back to Tony because he is the one with whom she belongs; or that she resigned herself to following her duty, which lies with Tony. The film clearly sides with the first option: in the closing scenes, Eilis is first presented as an experienced and confident migrant who teaches another Irish girl how to survive the trip to America. Then, she is shown embracing Tony, her voice over saying, “And you’ll realise that this is where your life is.” (2’19-24). In this version, Eilis finally knows where she belongs as she clearly identifies Tony and America as her home, whereas the novel ends on uncertainty and ambivalence.

Pour citer cette ressource :

Coline Pavia, Mobility and Immobility in Colm Tóibín’s Brooklyn: Migration as a Static Initiatory Journey, La Clé des Langues [en ligne], Lyon, ENS de LYON/DGESCO (ISSN 2107-7029), juillet 2020. Consulté le 29/01/2026. URL: https://cle.ens-lyon.fr/anglais/litterature/litterature-britannique/mobility-and-immobility-in-colm-toibin-s-brooklyn

Activer le mode zen

Activer le mode zen