The Terror of Desire in Victorian Visual Art

This article is based on a paper given at a conference entitled "Terror and Desire in 19th century Britain", organised by Virginie Thomas at Lycée Champollion (Grenoble) on the 21st of May 2024. Other presentations included:

-

The Desire for Terror in 18th-Century British Paintings (Agathe Viffray)

-

Fearing the passions of women. Female desire and sexuality in the nineteenth century (Véronique Molinari)

Introduction

Few Victorian writers represented the figure of the prostitute as directly as Dante Gabriel Rossetti did in his poem entitled “Jenny” that he wrote between 1848 and 1870, regularly revising the text. The first stanza of the poem rapidly shifts from a light-hearted celebration of the prostitute’s thoughtlessness to a more moralising qualification:

Lazy laughing languid Jenny,

Fond of a kiss and fond of a guinea,

Whose head upon my knee to-night

Rests for a while, […]

Poor shameful Jenny, full of grace

Thus with your head upon my knee;—

Whose person or whose purse may be

The lodestar of your reverie? (1991, 58)

“Jenny” is one of Rossetti’s most sensual poems and is representative of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (PRB)’s daring approach to desire. The PRB, which was the dominant pictorial movement of the Victorian society, was founded by Dante Gabriel Rossetti along with, among others, John Everett Millais, William Holman Hunt and Ford Madox Brown. This first PRB was followed by a second PRB led by William Morris and Edward Burne-Jones. This new pictorial movement inspired other artists, even if they did not officially belong to the movement; they all aimed at a rejuvenation of art, breaking away from The Royal Academy, and put forward a new artistic manifesto technically based on the vividness of colour and a precise representation of reality, but also thematically mixing social reality and literary heritage. They also brought to the front fleshly models - called Stunners - that revealed the artists’ deep interest in the representation of male desire. This interest could manifest itself in the depiction of social reality through the figure of the prostitute or the distanced recreation of the harem or the tepidarium. The PRB also used mythology to explore desire in all its different shapes from a chaste desire to a more erotic one. Finally, the representation of passion can be read as a cathartic way for the artists to experiment with their own personal desire for their models, whom they viewed as playing the antithetic roles of inspirational or stifling muses.

1. The social, cultural and historical recreations of desire in the Victorian era

1.1 The figure of the prostitute as the social embodiment of desire

Paradoxically, even though prostitution was largely developed in the Victorian era, very few pictorial representations of prostitutes can be found. One reason may be linked to the fact that artists preferred focusing on the recreation of mythological or literary episodes rather than fixing on the canvas a bleak aspect of the society they lived in and that could prove too shocking for Victorian prudishness. Yet, two PRB paintings stand out because they both stage the figure of a prostitute. One such representation is a diptych by William Holman Hunt: the first painting is entitled The Awakening of Conscience (1853-54) while the second one, The Light of the World (1853-54), represents one of the most important and widely reproduced biblical images of the 19th century.

The latter work represents Jesus Christ bringing the light of salvation to a world shrouded in darkness, whereas The Awakening of Conscience is, as Alison Smith puts it, “the fulfilment of the promise of the divine grace offered in The Light of the World” (2012, 134). It was a very daring move to suggest that a prostitute, considered a marginalised figure by Victorian society, could be in direct dialogue with Jesus Christ. Her status as a prostitute is suggested by the fact that she wears rings on each of her visible fingers except, tellingly, on her ring finger. Another clue about her being a kept mistress is the fact that she is loosely dressed, which metaphorically conveys her loose nature but also her distressed state of mind. This episode is supposed to represent the precise moment of revelation, of moral enlightenment of the woman who, while singing “Oft in the Stilly Night” – as the music score on the piano reveals –, reminisces about her past innocence, also symbolised by the prelapsarian Garden of Eden whose reflection can be seen in the background. The dark setting, which suggests the moral darkness the young woman is trapped in, is brightened by the vivid colours of the Turkish carpet, the rosewood piano, the bell pull and the pelmet above the window. Two clues in this oversaturated canvas ominously foretell the future of the fallen woman, should she not pay attention to the Light of the World. Indeed, a cat playing with a bird stands as the dark double of the would-be lover also playing with the future of his mistress. Both the bird and the mistress find themselves trapped by darker forces. The moral message addressed to both male and female viewers in this symbolically saturated composition is also highlighted by the frame displaying bells – the symbol of warning – and marigold – the symbol of sorrow. The inscription at the bottom of the frame is taken from Proverbs 25:2: “As he that taketh away a garment in cold weather, so is he that singeth songs to a heavy heart”. The burden of sorrow is counterbalanced by the presence at the top of the frame of a star, the symbol of faith but also the only possible key to the woman’s salvation. This moral warning sounds rather paradoxical in so far as the model for the kept mistress who is supposed to experience a moral – and religious? – awakening in order to escape her gloomy future was in fact Annie Miller, a working-class model who was Hunt’s own kept mistress...

Dante Gabriel Rossetti also attempted to represent the figure of the prostitute in the unfinished painting Found (1854-81).

Its theme, that of a fallen woman confronted by her innocent past, was similar to The Awakening of Conscience ((Hunt was the first of the two painters to work on this subject. Rossetti was worried that he might be accused of plagiarism because of the slow progress that he made with his work, as he kept working on the painting, taking it up and leaving it aside many times throughout his life. He continued working on it as late as until 1881 but, in spite of the help of his studio assistants, he never completed it.)). Rossetti’s only pictorial attempt at a modern life moral subject represents an urban prostitute accosted by a former suitor, a reminder of her earlier, more virtuous life in the countryside. The setting of a London street at dawn suggests the idea of enlightenment, the realisation of the moral implications of the fallen woman’s dissolute way of life as in the previous painting by Hunt. Under the weight of her shame, the woman has fallen to her knees against the reddish wall of what seemed, in the preparatory drawing, to be a churchyard. The white calf tied to go to the market symbolises the innocent animal trapped to be sold, suggesting the situation of this woman who has fallen victim to a patriarchal society, as evidenced by the guard stone or chasse-roue. This surprising element can be viewed as the phallic double of the man towering over his former lover. Once again, a personal dimension can be added to the interpretation of this painting, as Rossetti used the head of Fanny Conforth, his mistress, to represent the fallen woman. Even if Rossetti very rarely chose to visually represent the prostitute as a Victorian social characteristic, he devoted many of his female pictorial representations to biblical or literary repentant sinners such as Mary Magdalene or Guinevere; this thematic interest may explain why Rossetti kept returning to Found, in spite of the technical difficulties he encountered.

The scarcity of the representations of prostitutes due to the Victorian taboo about the reality of what was perceived as a social plague did not mean that the artists of the time avoided the representation of desire. They used a distanced setting to satisfy the male viewer’s Lacanian scopic appetite. The 19th-century oriental trend gave the artists an extraordinary opportunity to focus more particularly on the locus by excellence of male desire, ie the harem.

1.2 The Oriental phantasm: the harem between the myth and reality of desire

John Frederick Lewis was a famous Oriental painter of the time, who arrived in Egypt in 1841 and remained there for ten years. Lewis inaugurated his public career as an Orientalist painter in 1850 with the most ambitious harem painting ever attempted by a British artist and entitled The Hhareem ((For a partial view of the painting, see The Hhareem, Cairo | Lewis, John Frederick (RA POWCS) | V&A Explore The Collections.)). The spelling with a double h was meant to be reminiscent of Arabic spelling, thus suggesting a high level of authenticity. In spite of this apparent intention, the representation is far from being as accurate as it may seem at first sight, flirting between veracity and fantasy. The master of the harem is a wealthy, polygamous Turkish chieftain. He sits on the couch with his three wives: on the left, his Georgian wife, then his Circassian wife and finally his Greek wife. The Georgian woman is the ruling lady of the harem, as she is the mother of the master’s son nestling against her. The black servants are Abyssinians and the unveiled woman, the latest arrival. Beyond the representation of a geographically remote cultural reality, that of the Oriental harem, the watercolour becomes a sort of racial taxonomy as the canvas stages various exotic embodiments of male desire, not only through gendered representations but also through racial considerations. To quote Nicholas Tromans: “The new Abyssinian plays her conventional role as a kind of erotic natural anomaly, the woman who achieves a beauty of form and feature on a level with her Caucasian competitors ‘despite’ her African skin” (2008, 132). In most of the artist’s harem paintings, the presence of a dominant male figure can be interpreted as the Victorian male viewer’s double whose fantasies of Oriental indulgence could be at last fulfilled. Yet, the reading of the paintings by John Frederick Lewis is more complex. For example, here, space is dominated by women but there seems to be an unbridgeable gap between the viewer’s space and the Oriental women’s. They are more hidden than revealed and eye contact seems to be impossible: the only direct gaze in the viewer’s direction is that of the antelope on the right, an elusive animal, which contrasts with the haughty, and therefore hardly seductive, attitudes of the women who are not, as Nicholas Tromans underlines, “what admirers of Orientalism’s usually flirtatious beauties, contained in almost claustrophobically intimate interiors, had come to expect” (2008, 32). The laughing expression of the Abyssinian woman standing in the background could be an indirect comment both on the harem master’s mesmerised gaze staring at the newcomer and on the viewer’s own fascinated gaze.

A sharp contrast emerges with other Orientalist paintings which did not stage this large and distant representation of exotic desire but created a much more claustrophobic atmosphere with lascivious female figures. In Leila by Frank Dicksee (1892), the confined atmosphere is rendered thanks to a moucharaby in the background blocking any perspective, and the dominant red colour which traps the viewer into the sensual space of this Odalisque who, in spite of her Oriental name signifying “the daughter of darkness”, displays Western features. The whiteness of her skin, echoed by the whiteness of the lilies on the left, contrasts all the more with the sulphurous red of her lips, clothes and surrounding drapery. The duality of the character is symbolised by the opposition between the lily, a Marian attribute traditionally associated with purity, and the leopard skin on the right which suggests the hidden bestiality of this sensual character. The medium framing, contrasting with John Frederick Lewis’s long shots, invites the viewer to enter the scene and share a frontal gaze with this desiring and potentially desired daughter of darkness.

Oriental representations of the harem were thus a way for Victorian artists to come close to the experience of desire while setting it at a distance thanks to geographical remoteness. They also used temporal distance as a subterfuge to stage sulphurous female bodies.

1.3 The historical distancing of desire

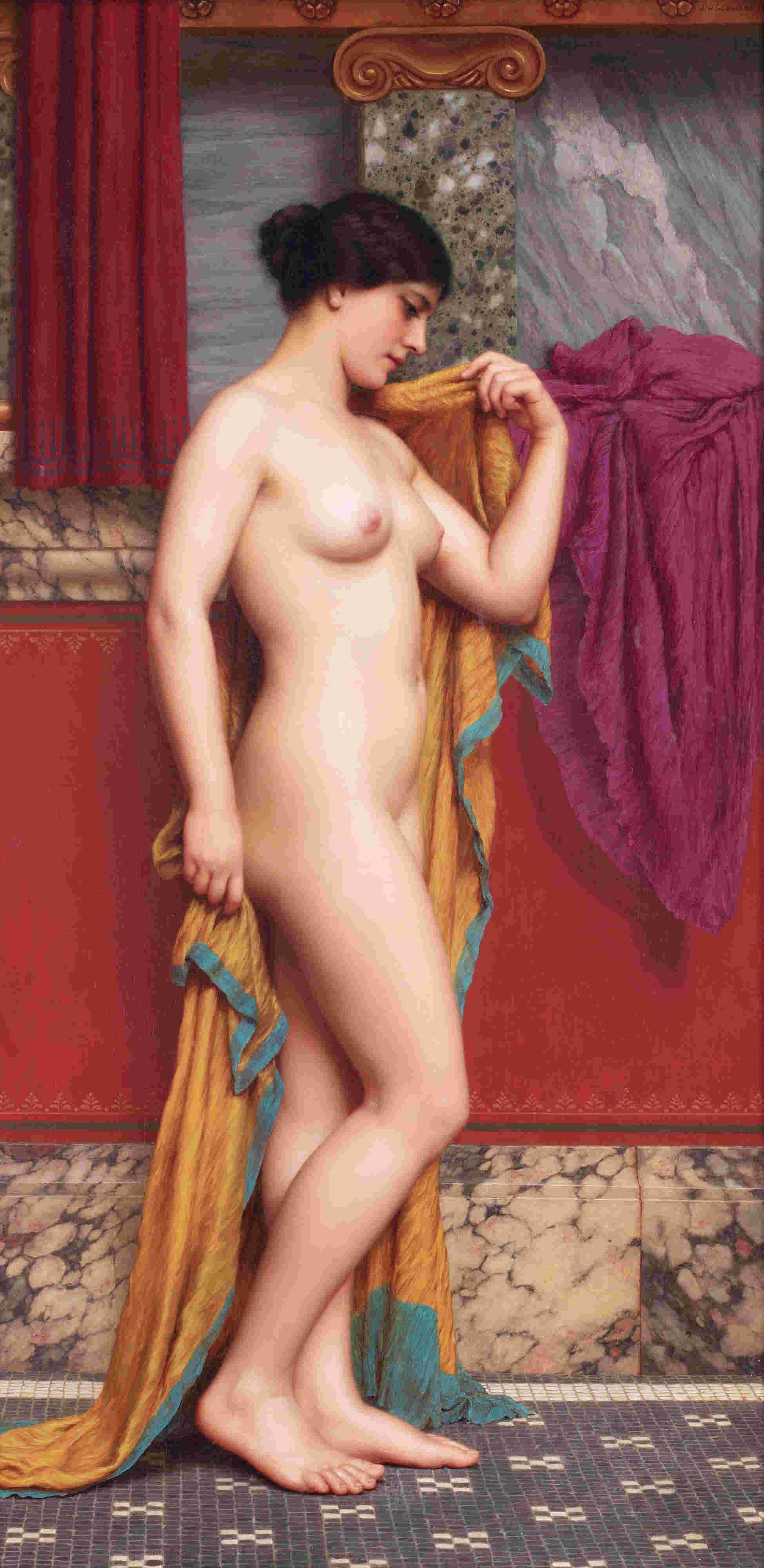

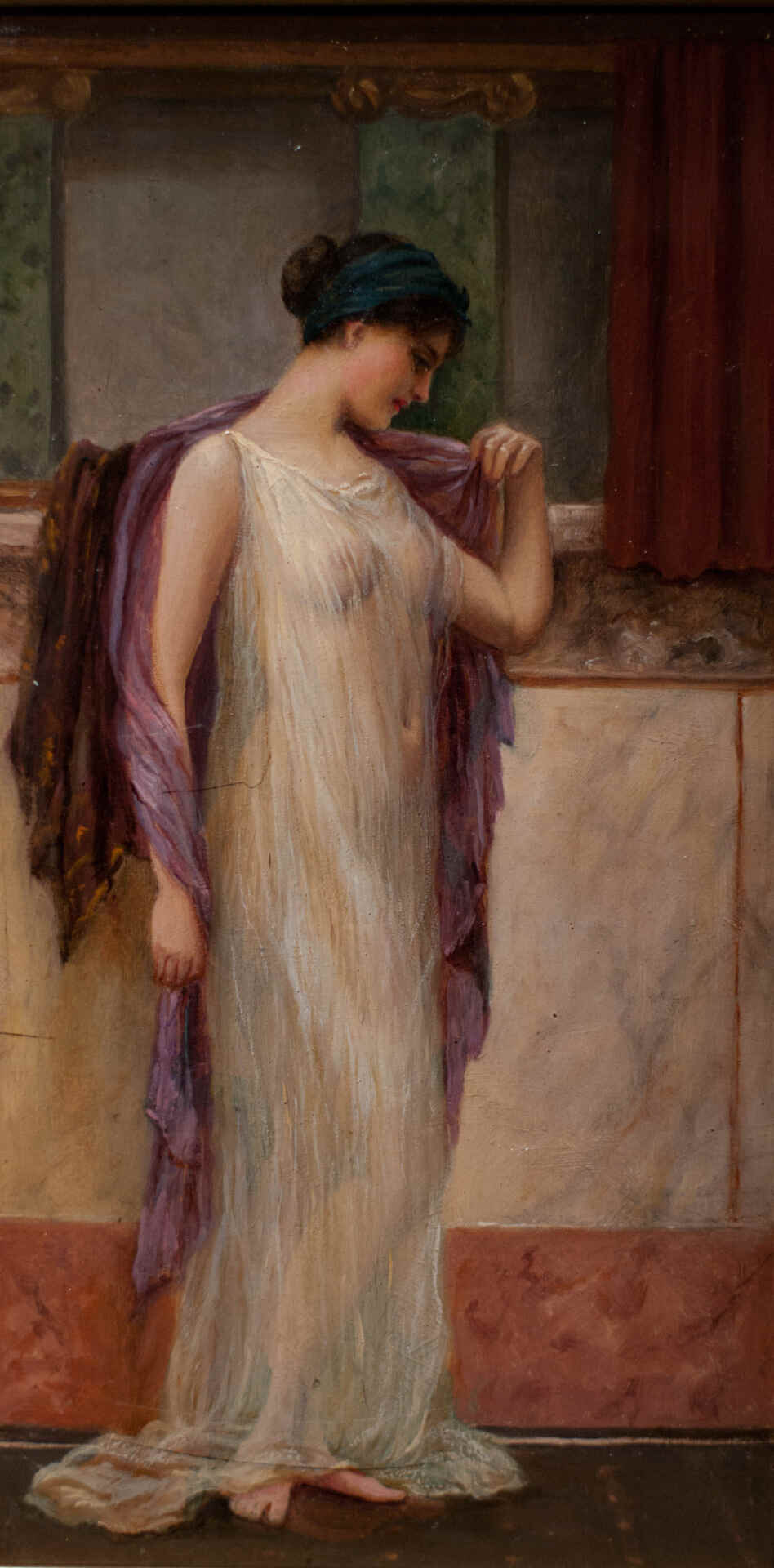

John William Godward was a neoclassical painter who was deeply inspired by Lawrence Alma-Tadema and his keen interest in the representation of ancient architectural monuments. Both were fascinated by archaeology and visited Italy. John Willliam Godward first visited Naples in 1904-05 and was struck by the beauty of Pompeii. He then returned to Italy in 1911 and remained in the Province of Verona for ten years. In the Tepiderium (c. 1913) is a canvas that Godward painted in Rome and that brought to an end his series of imposing nude paintings.

The tepidarium was the tepid room of Roman baths where, in the women-only section, one was supposed to go after taking off one’s clothes and before entering the caldarium. Even if Godward closes the neoclassical period at the beginning of the 20th century, he is still under the spell of another tepidarium painted this time by his friend and master Alma-Tadema in 1881 (In the Tepidarium). In the two paintings, the nudity of the women’s bodies enables the viewers to satisfy their scopic appetite. It is even more interesting to study the evolution between the study for Godward’s painting and the final version in so far as the first draft originally staged the same young woman but with a transparent palla, redolent of the Venus Genitrix, which disappears in the final painting, thus offering this young Roman’s whole body to the gaze of the viewer.

The dexterity with which Godward rendered the marble in the background can also be felt in his faithful representation of the softness and freshness of the skin. The position of the Roman woman is inspired by the dignified classical statue of Venus Genitrix but departs from the celebration of the motherly body even if it still remains far from the sulphurous position of In the Tepidarium (1881) by Alma-Tadema.

The latter invites the viewer to a complete sensorial experience from the cold of the marble to the heat of the animal skin and the humid atmosphere which accounts for the Roman woman’s rosy cheeks. The red colour of the camellia tree also adds fleshly hues which tend to highlight the bodily dimension of this painting. Indeed, Alma-Tadema created an eroticised painting with the naked body strategically hidden behind the ostrich fan. The strigil in the woman’s right hand also aims at suggesting the close contact with the female body. The purpose of this staging was clearly to arouse male desire with the naked body and the open lips. The size of the painting indicates that it was intended for a gentleman’s smoking-room or library. The company A&F Pears imagined using this picture as a soap advertisement but the idea was quickly given up because the canvas was deemed far too shocking.

Representing bodily desire in Victorian times was a slippery slope for artists who had to compose with rigid Victorian mores. They had to use subterfuges to represent the reality of desire, rarely daring to address the figure of the prostitute, preferring to use the geographically distant Oriental Odalisque or the temporally remote Roman beauty. They went a step further by frequently resorting to mythological or literary figures to give a more morally acceptable shape to the representation of male desire, as well as what male artists perceived as female desire.

2. Mythological and literary embodiments of desire

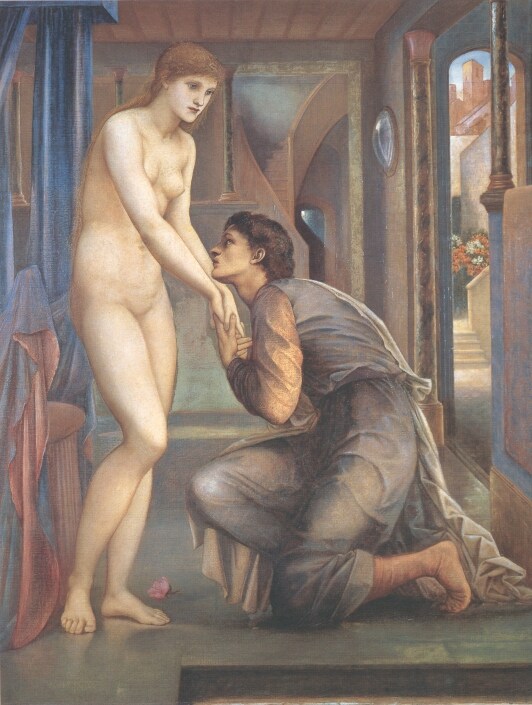

2.1 Pygmalion or the sublimity of male desire

Edward Burne-Jones was the leading figure of the second generation of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood which dominated the artistic scene until the beginning of the 20th century. He was also famous for the numerous series that he devoted to mythological figures or episodes. He chose to illustrate the myth of Pygmalion who inspired him no less than twenty-eight drawings that he used to elaborate a sequence of four paintings. This series illustrated the poem entitled “Pygmalion and the Image” that his close friend William Morris wrote. The summary that Morris placed at the beginning of his book served as a springboard for Burne-Jones’s imagination:

A MAN OF CYPRUS, A SCULPTOR NAMED PYGMALION, MADE AN IMAGE OF A WOMAN, FAIRER THAN ANY THAT HAD YET BEEN SEEN, AND IN THE END CAME TO LOVE HIS OWN HANDIWORK AS THOUGH IT HAD BEEN ALIVE: WHEREFORE, PRAYING TO VENUS FOR HELP, HE OBTAINED HIS END, FOR SHE MADE THE IMAGE ALIVE INDEED, AND A WOMAN, AND PYGMALION WEDDED HER. (1903, 3)

This series, depicting Maria Zambaco, was first ordered by her mother Euphrosyne Cassavetti, at a time when Edward Burne-Jones was deeply in love with Maria, in spite of his marriage bonds with Georgiana. The series stages the representation of an artist torn between the creation of an aesthetic ideal and the reality of his own physical passion. The echoes between Pygmalion’s inner torment and Edward Burne-Jones’s own division add another layer of interpretation to the series. In The Heart Desires (1868-69), Pygmalion meditates about the perfection of the human body represented by the group of sculptures redolent of the Three Graces.

The young women passing by in the street are represented as mundane and frivolous, in an attempt to underline the superiority of the three statues whose disjointed, quasi modernist marble reflection signals their belonging to another, superior level of reality. In The Hand Refrains (1868-69), the smooth perfection of the female body created by Pygmalion is underlined thanks to the fragments of rock at the statue’s feet.

The Godhead Fires (1868-69) was admired for its Raphaelite quality and stages Venus giving life to Galatea, whose head was modelled after Maria Zambaco, even if the resemblance tended to be blurred in the later versions.

Far from underlining the fleshly dimension that Galatea finally acquires in the last panel of the series, The Soul Attains (1868-69) still grants Galatea a marmoreal body and leads the viewer to wonder if Pygmalion kneels in front of the result of his physical desire as a man or in front of the accomplishment of his aesthetic quest as an artist. The title of the last painting of the series rather tends to lead us in the second direction, sublimating male desire as a form of spiritual quest.

2.2 Chaste female desire: Elaine / Lady of Shalott

The Victorian artists also turned to the representation of what was perceived at the time as the only acceptable form of female desire: chaste desire, ie innocent love within the sacred bonds of marriage. They achieved this through the representation of literary characters that illustrated the dichotomous division celebrated by Alfred Lord Tennyson in the original subtitle to Idylls of the King (1809-1892), “The True and the False”. Tennyson, who was Victoria’s poet laureate, rewrote the medieval Arthurian cycle to propose different female models who revealed antithetic (and stereotypical) approaches to desire: Guinevere – the unfaithful wife –, Vivian – Merlin’s lethal temptress –, Morgan – Arthur’s fatal half-sister. These false women were opposed to a quasi unique virtuous Arthurian character: Elaine of Astolat or the Lady of Shalott, as she is more commonly known in Tennyson’s other Arthurian poem that inspired so many artists of the time, was a chaste young woman who falls in love with Lancelot. Some painters chose to underline her innocent love for Lancelot as is the case of John Melhuish Strudwick’s Elaine (1891). This painter was deeply inspired by Edward Burne-Jones, whom he worked with as a studio assistant. Like Burne-Jones, he developed a style that blended medieval and Quattrocento influences, adding a meticulous attention to detail more specifically in the rendering of draperies and accessories. Elaine is a chaste young girl protected by her brothers, but she discovers the torments of love after her meeting with Lancelot who agrees to bear her colours during a tournament, leaving his far too recognisable shield under Elaine’s supervision. Then, Lancelot cruelly abandons Elaine without even bidding her goodbye to return to Guinevere, his adulterous mistress. Elaine dies because of her broken heart but she lived on in Victorian imagination as she came to embody the perfect young lady of the house with a heavy sense of duty. This moral perfection is rendered here thanks to the quiet medieval interior. The whiteness of her dress is echoed by the cloth in the background and the lilies next to her feet. The latter remind the viewer of her name “the lys of Astolat” while also creating a link with the Virgin Mary’s traditional attribute. The golden brown of the rest of the painting sets into relief the figure in the foreground, constituting a sort of faded halo around this incarnation of despair. Elaine has abandoned her book, her lute, her prie-Dieu to devote her entire life to the memory of Lancelot whose shield is invading Elaine’s wasted life. Yet, by turning away from the virtues represented on the chest she is sitting on, she represents the danger of desire that can lead even the purest to a deadly end.

However, Elaine of Astolat, the chaste Arthurian young girl, did not benefit from the same posterity as the Lady of Shalott, her literary double. Indeed, Tennyson’s Lady of Shalott found a greater resonance for more than twenty years because of her more ambiguous identity, verging on the magic, whereas Elaine was deemed too wise and maybe too corseted by society’s expectation of what a young woman’s love should look like. Many illustrations and paintings were created of the Lady of Shalott, but the most famous is undoubtedly the one painted by William Holman Hunt from 1888 to 1905.

Hunt was fascinated by Tennyson’s work: he completed his first illustration of the poem, a pen and ink drawing, in 1850. The Lady of Shalott (1832) tells the story of a lady cursed to live alone in a tower, weaving scenes that represent the world she must only look at through a mirror. Hunt’s visual representation of the poem concentrates on the central moment of crisis when, seeing in her mirror the figure of Sir Lancelot on the road to Camelot, the lady defies the curse. The representation of the Lady of Shalott, both in its textual and pictorial form, symbolically focuses on women’s behaviour and more particularly on their sexual identity. As Tim Barringer underlines, “The frank expression of the lady’s sexual desire for Lancelot contravened the powerful ideological demand that women’s sexuality should be passive and related solely to reproduction” (2012, 224). The heroine’s wild hair symbolises her sexual identity, showing the desperate attempt of the young lady to escape the moral constraints of the Victorian society suggested by the network of threads that trap her in the middle of her loom. The impression of imprisonment is reinforced by the omnipresence of circles in the painting: the oblong paintings on the walls, the large mirror in the background showing Lancelot’s reflection, the enormous loom and the small multicoloured balls of thread. The movement of her arms trying to undo the threads creates a curve trapping her own body. The weaving presented on her loom and the impressing display of her hair transform The Lady of Shalott into a resurgence of the castrating figure of Medusa. The Lady’s wild hair symbolises her awakening to sensuality and sexual desire under the disapproving eye of the mythological and biblical figures peopling the embedded paintings: on the left, the Virgin Mary is supposed to offer a model to emulate for the Lady of Shalott, that of female purity and ideal motherhood echoed by the presence of Marian lilies in the bottom-right-hand corner; on the right, Hercules in the garden of the Hesperides acts as the prefiguration of Jesus Christ and his twelve labours symbolise the victory of good over evil. The frowning gaze of Hercules on the Lady invites the viewer to share the same disapproval in front of this scene of disturbing sexual arousal in so chaste a character.

2.3 Explicit erotic female desire

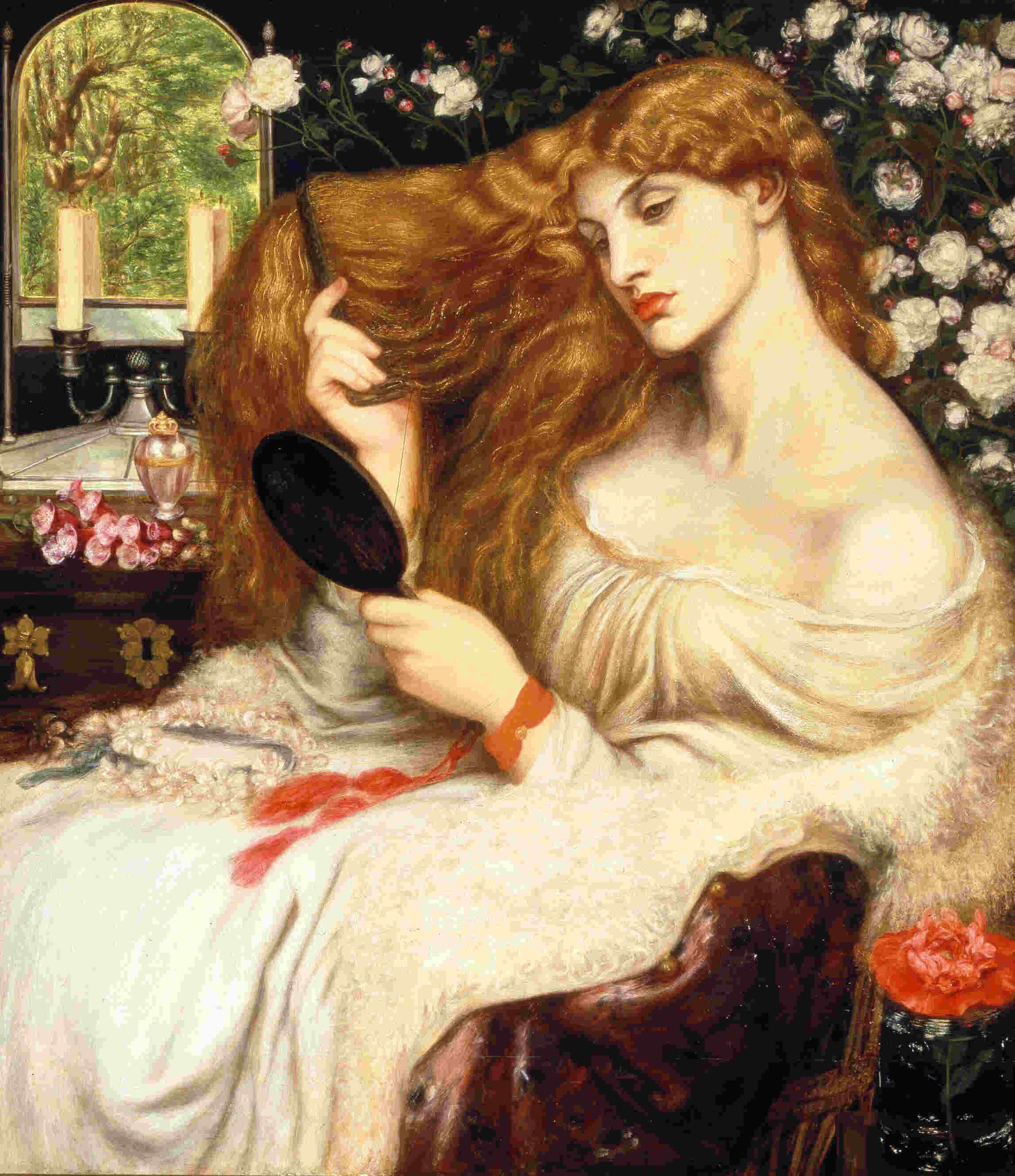

Pre-Raphaelite paintings were also famous for the staging of explicitly sensualised women who were called Stunners: these models were famous for their sensuous red lips and abundant head of hair meant to suggest their erotic nature. Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s paintings are the most emblematic and were met either with fascination or disapproval. Indeed, Rossetti was severely criticised by the critic Robert Buchanan (1841-1901) who labelled both his poetic and pictorial art as “The Fleshly School of Poetry”. This derogatory title aimed at conveying the moral outrage that such representations could cause in the prudish Victorian context. The bodily dimension of Rossetti’s protagonists, and more notably of the female heroines, exposed their erotic appeal but also the sensual nature of women. One may take for example the representation of the proto-model of female sensuality and desire: the figure of Lilith, Adam’s first spouse, in Rossetti’s eponymous painting (1868).

The overcrowded setting deprives the beholder of any possibility of distance. The viewer is directly confronted to the corporeality of the lady and can find no escape, not even in the background. The beholder thus faces Lady Lilith’s lethal eroticism, suggested by the animal dimension of her fur robe and the red poppy on the right that echoes the touches of red of her bracelet and of her lips. Her loose hair acts, as in the case of the Lady of Shalott, as a symbolic reminder of her sexual nature. Indeed, Lilith is famous for her sexual appetites, chasing men to satisfy her bodily drives. Yet, Rossetti hides the lethal dimension of Lilith’s desire behind the appearance of a beautiful flower-woman surrounded by white purity. Nevertheless, the oversaturated space suggests the stifling power of this woman. It is also important to note that Dante Gabriel Rossetti chose his mistress, Fanny Cornforth, to pose as Lilith in the first version of the painting, thus projecting his own sexual relationship with his model onto the representation of this powerful female figure.

Desire can therefore range from the sublimated purity of male passion to the fear-inducing representation of women’s sexuality, which would lead the male spectator to a deadly end. This typology of desire was meant to echo the Victorian taxonomic opposition between true love and false desire. Yet, the artist also found a way to represent their own personal approach to desire in so far as, more often than not, the women represented could range from an inspiring muse to a destructive mistress.

3. Representing the artist’s desire

3.1 Inspirational muses

The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood was surrounded by numerous women, be they models, muses, artists or mistresses. One might take for example, the figure of Maria Zambaco, the heroine of an eponymous portrait made by Burne-Jones in 1870.

Zambaco met Burne-Jones in 1866 and served as his muse for three years, before becoming his pupil and later on his mistress. Although Burne-Jones fell more and more deeply in love with her, he refused to leave his long-enduring wife, Georgiana, and, in 1869, decided to split up with Maria. She then tried to commit suicide twice and Burne-Jones was deeply tormented by the events. It took him a few months to be able to go back to his work and the best way he found was to incorporate Maria’s face into some of his most remarkable works, such as The Beguiling of Merlin (1874) ((You can find an analysis of the painting in the following article: Images of Erudite Femininity: Capturing the learned/knowledgeable woman in 19th-century visual arts (part 1: Pre-Raphaelite artists’ male perspective).)).

In Maria Zambaco, the portrait he made of her a year after their separation, Burne-Jones turned the model into a Venus, as indicated by the presence of a cupid in the background. Maria holds a white dittany in her hand, a symbol of passion in the language of flowers, and her book opens on a miniature image of The Love Song, another painting by Burne-Jones (1868-77).

These two elements are a sublimated reminder of his love for Zambaco and contrast with the symbolism of the blue colour and of the irises which are traditional attributes of the Virgin Mary. This ambivalence is redolent of two paintings by Dante Gabriel Rossetti who also staged an illicit love, this time for a married model who is the heroine of The Blue Silk Dress (1868) and Mariana (1870).

In these two canvases, Dante Gabriel Rossetti donned his model with the Marian colour while daringly celebrating the beauty of one of his favourite models and mistress, Jane Morris, who was the wife of his close friend William Morris.

One may wonder if the representation of these obsessive mistresses might not reveal the artist’s fear of being stifled by desire - which is also conveyed in the numerous representations of women strangling their lovers - but also, indirectly, the fear that women might not be a mere object of desire.

3.2 The fear of a stifling / strangling desire

John Everett Millais’s The Crown of Love (1875) is a good illustration of this fear of being suffocated by desire.

This painting was inspired by George Meredith’s poem which tells the story of a young man who has won the love of a princess and is condemned to take her to a mountain-top reaching the sky. The ascent quickly becomes tragic as a storm breaks out. Understanding that they will die, the princess begs her young lover to leave her here but he refuses. They both die and reach the sky hand in hand. The painting refers to a specific excerpt from the poem when the princess says “Ah, hero live! Unloose thy hold: / O drop me like a cursed thing. / See’st thou the crowded swards of gold?: / They wave to us Rose and Ring” (1912, 139). What is most interesting in the painting is the intensity of the moment conveyed both by the man’s dynamic pose and the focus on the princess’s face supposed to communicate her fearful entreaty. The tempest is suggested by the dark colours, the wind in the hair and the beret on the ground. The brown colours of this Scottish landscape also suggest the tragic end about to occur. Yet, the man’s hold mentioned in the poem is doubled here by the princess’s arms around the man’s neck, which seem to be strangling him rather than pleading. Consequently, the red sleeves and beret reinforced by the red touches in the landscape or on the princess’s outfit seem to pinpoint the responsibility of the man’s burning desire that will lead him to his end.

This topos of the strangling power of a woman is frequent in Pre-Raphaelite canvases. Another very famous example is the representation of La Belle Dame Sans Merci by John William Waterhouse (1893).

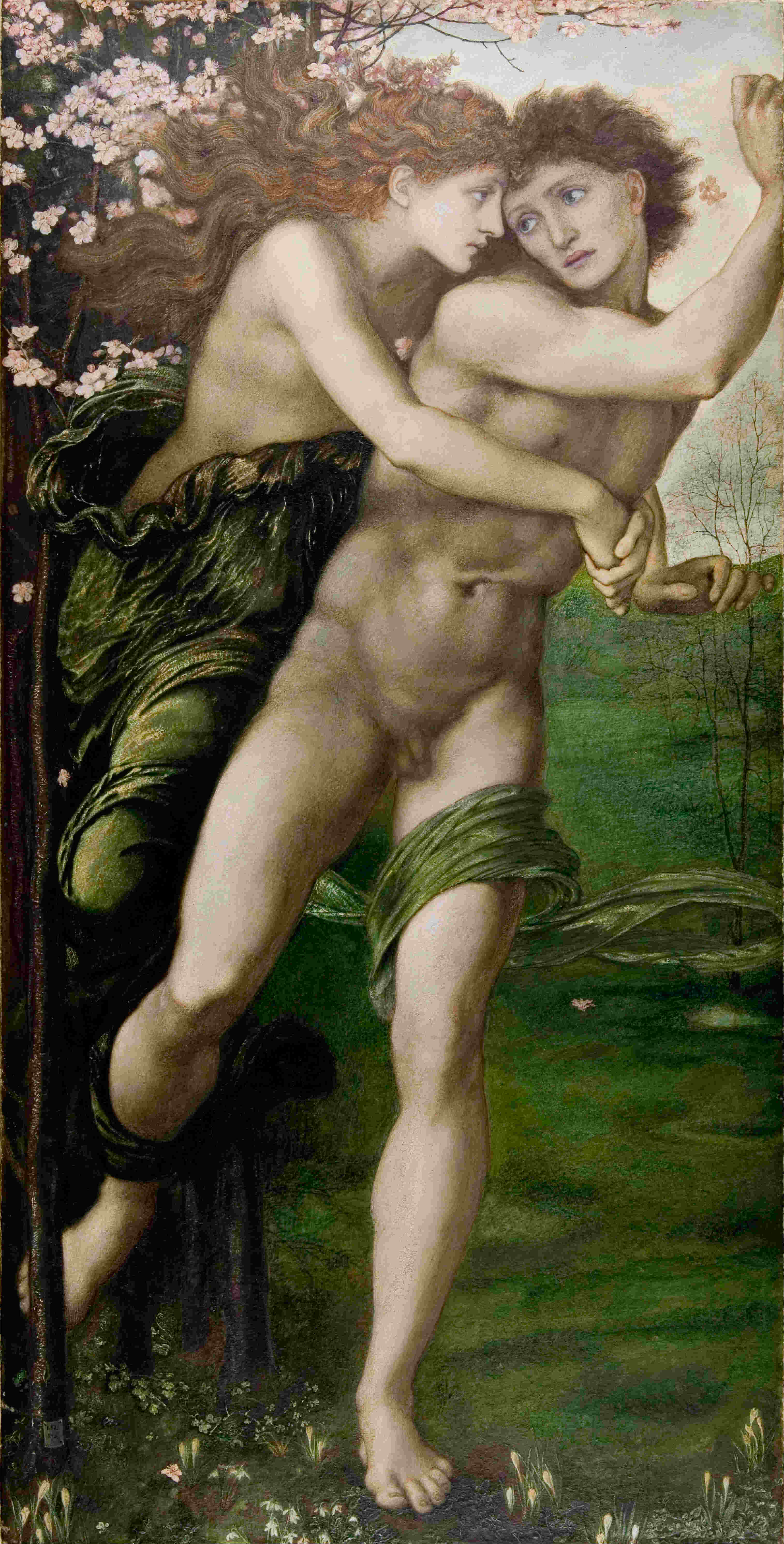

This painting was the illustration of a poem by John Keats who staged a far more Machiavellian young lady. Indeed, La Belle Dame uses her charms to lead knights to a lethal outcome. Desire remains the weapon that strangles the male victims: this process is suggested thanks to the knotted hair around the knight’s neck. But, beyond these literary recreations, Pre-Raphaelite artists also resorted to mythological figures to, maybe, sublimate their unconscious fear of being possessed and deprived of their artistic and / or personal independence as in Burne-Jones’s Phyllis and Demophoön (1870).

This painting is a remarkable tribute to the naked bodies traditionally represented during the Classical Renaissance and also to Ovid’s Heroides. The story is that of Phyllis who falls in love with Demophon, Theseus’s son, during the former’s visit to her father’s royal court. Demophon leaves but promises to return. As he fails to do so, Phyllis commits suicide and the Gods decide to turn her into an almond tree. When Demophon finally returns, he goes to see this almond tree and, full of remorse, kisses it. At this very moment, Phyllis comes out of it to forgive her unfaithful lover. What is noteworthy here is the fact that the heroine’s face was modelled on Maria Zambaco’s features, Burne-Jones’s lover, and at the back of the canvas Burne-Jones inscribed a Latin quote which shows the heavily personal layer that has to be added to this mythical representation, turning the painting into a cathartic work: [“dic mihi quid feci? nisi non sapientier / amavi”, ie “What have I done? Except perhaps to have lov’d you to excess”]. It is difficult to know if Maria and Burne-Jones’s liaison was a matter of common knowledge but the critics and the viewers at the time were shocked by the representation of male genitalia and by the suggestion of a love chase initiated by a woman. Her embrace seems impossible to escape because of the doubling of her folded arms with her tied clothes around Demophon’s calf and thigh.

To conclude, the vision of desire by the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood and the artists of the 19th century at large ranged from a social reality, that of prostitution, to a geographical, temporal, literary or mythological sublimation. Yet, this sublimation was also a way for the artist to express their ambivalent relationship with their own desire that could be defined both as a spur for their creation or as a threat that might stifle their creativity and lead them to “the depths of the sea”, as the title of a 1886 painting by Burne-Jones suggests. Indeed, a difficult balance had to be found between the warmth of desire and the coldness of the havoc it can cause: art can be seen as a space of experimentation, to represent and meditate over this delicate conciliation.

Notes

Bibliography

Paintings

ALMA-TADEMA, Lawrence. 1881. In the Tepidarium. National Museums Liverpool, oil on canvas, 24.2 cm x 33 cm.

BURNE-JONES, Edward. 1868-69. The Godhead Fires. Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery, oil on canvas, 143.7cm x 116.8 cm.

---. 1868-69. The Hand Refrains. Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery, oil on canvas, 98.7 cm x 76.3 cm.

---. 1868-69. The Heart Desires. Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery, oil on canvas, 99cm x 76.3 cm.

---. 1868-1877. The Love Song. Metropolitan Museum of Art, oil on canvas, 114.3 cm x 155.9 cm.

---. 1870. Maria Zambaco. Private collection, oil on canvas, 76.3 cm x 55 cm.

---. 1870. Phyllis and Demophoön. Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery, body colour and watercolour, 93.8 cm x 47.5 cm.

---. 1868-69. The Soul Attains. Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery, oil on canvas, 99.4cm x 76.6 cm.

DICKSEE, Frank. 1892. Leila. Private collection, oil on canvas, 100 cm x 126 cm.

GODWARD, John William. 1913. In the Tepidarium. Private collection, oil on canvas, 98.5 cm x 48.5 cm.

---. 1913. In the Tepidarium (study). Collection Pérez Simón, Mexico.

HUNT, William Holman. 1853-54. The Awakening of Conscience. Tate Britain, London, oil on canvas, 76.2 x 55.9 cm.

---. 1888-1905. The Lady of Shalott. Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, Hartford, Connecticut, oil on canvas, 188.3 cm x 146.4 cm.

---. 1851-54. The Light of the World. Keble College, Oxford, oil and gold leaf on canvas, 122 x 60.5 cm.

LEWIS, John Frederick. 1850. The Hhareem. Private collection, watercolour, 133 cm x 88.6 cm.

MILLAIS, John Everett. 1875. The Crown of Love. Pérez Simon Collection, Mexico, oil on canvas, 129.5 cm x 87.8 cm.

ROSSETTI, Dante Gabriel. 1868. The Blue Silk Dress. Society of Antiquaries of London, Kelmscott Manor, oil on canvas, 101.5 cm x 90.2 cm.

---. 1854-81. Found. Yale Center for British Art, New Haven, Connecticut, oil on canvas, 47.0 cm x 39.4 cm.

---. 1868. Lady Lilith. Delaware Art Museum, oil on canvas, 97.8 cm x 85.1 cm.

---. 1870. Mariana. Aberdeen Art Gallery, oil on canvas, 109.8 cm x 90.5 cm.

STRUDWICK, John Melhuish. 1891. Elaine. Private collection, oil on canvas, 79 cm x 58.5 cm.

WATERHOUSE, John William. 1893. La Belle Dame Sans Merci. Hessisches Landesmuseum Darmstadt, oil on canvas, 112 cm x 81 cm.

Works cited

BARRINGER, Tim, ROSENFELD, Jason and SMITH, Alison. 2012. Pre-Raphaelites. Victorian Avant-Garde. London: Tate Publishing.

MEREDITH, George. 1912. “The Crown of Love”, in George Meredith, Poems. Volume 1. London: Surrey Edition.

MORRIS, William. 1903. Pygmalion and the Image. New York: Robert Howard Russell.

ROSSETTI, Dante Gabriel. 1991. “Jenny”, in Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Selected Poems and Translations. New York: Routledge.

TROMANS, Nicholas. 2008. The Lure of the East. British Orientalist Painting. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Pour citer cette ressource :

Virginie Thomas, The Terror of Desire in Victorian Visual Art, La Clé des Langues [en ligne], Lyon, ENS de LYON/DGESCO (ISSN 2107-7029), février 2025. Consulté le 18/02/2026. URL: https://cle.ens-lyon.fr/anglais/arts/peinture/the-terror-of-desire-in-victorian-visual-art

Activer le mode zen

Activer le mode zen