Images of Erudite Femininity: Capturing the learned/knowledgeable woman in the 19th-century visual arts (part 1: Pre-Raphaelite artists' male perspective)

This article is based on a paper given at a conference entitled "Women and Knowledge in 19th century Britain", organised by Virginie Thomas at Lycée Champollion (Grenoble) on the 24th of May 2023. Other presentations included:

-

A voice and a place of one’s own: women, knowledge and empowerment in Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre (Christine Vandamme)

-

“Captives of ignorance” ? Women, education and knowledge in the Victorian period (Véronique Molinari)

-

Images of Erudite Femininity: Capturing the learned/ knowledgeable woman in the 19th-century visual arts. Part 2: Pre-Raphaelite artists’ female perspective (Agathe Viffray)

Introduction

The PRB or Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood is often defined as Victorian avant-garde, a pictorial revolution that happened at a time of historical and social revolutions as well. Tim Barringer and Jason Rosenfeld introduce the PRB as follows:

Pre-Raphaelitism belongs among the very earliest of the historical avant-gardes. The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood was founded in 1848 in a world that was recognisably modern: it was marked by a dramatic technological and social change, the globalisation of communications, rapid industrialisation, turbulent financial markets and the unchecked expansion of cities at the growing expense of the natural world. Every aspect of life was changing quickly. Traditional social relationships, beliefs and patterns of behaviour were challenged as never before, while evolving into those familiar to the world today. (2012, 9)

The first PRB made up of John Everett Millais (1829-1896), Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828-1882), William Holman Hunt (1827-1910) and Ford Madox Brown (1821-1893) clearly aimed at radical innovative technical and stylistic choices that would be the mirror of the changing times the artists lived in. The same goal was espoused by the second Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, which emerged only a few years after the creation of the first PRB and introduced new leading figures, such as Edward Burne-Jones (1833-1898) and William Morris (1834-1896). Other artists incrementally gravitated around the PRB and adopted their revolutionary technique and thematic choices without formally belonging to their group like Frederick Sandys (1829-1904) or, later on, John William Waterhouse (1849-1917). Yet, what is striking about this revolutionary British avant-garde, be it defined in a restricted or broader way, is the very conservative representation that they granted to the relationship between women and knowledge. Women's social status and intellectual aspirations were slowly evolving in the Victorian period, but a quasi unique representation of learned women was drafted by male artists as the figure of an unnatural knowledgeable woman, a monstrous bloody prophetess or sorceress hiding the threat of a castrating Medusa.

Unsurprisingly the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood was initially premised on the exclusion of women. Nonetheless, numerous female artistic figures also gravitated around the PRB, such as Christina Rossetti (1830-1894), Dante Gabriel Rossetti's sister, Elizabeth Siddal (1829-1862), Jane Morris (1839-1914), Julia Margaret Cameron (1815-1879)... All these women embodied the roles of stunners or Femmes Fatales for their male counterparts but were also muses, painters and photographers, writers and figures of knowledge themselves. They were therefore intimately concerned by the theme of knowledgeable women. While they mostly illustrated the relationship between women and knowledge through the same figures as their male counterparts, they treated their subjects with less abhorrence and judged them less severely. Female artists found several ways to fit in the pre-Raphaelite beauty canon while both acknowledging and recognising the legitimacy of the learned woman’s figure.

This paper proposes to contrast the anamorphic representation of the learned / knowledgeable woman that was imagined by the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood and the Pre-Raphaelite Sisterhood at the same period. Were women artists condemned to see their sisters' nature through the male lens or did they manage to find a gaze of their own to shed a more positive light on the relationship between women and knowledge?

1. Domestic and domesticated female knowledge

The ideal relationship between women and knowledge in the Victorian era can be illustrated by the work created by John Callcott Horsley (1817-1903), an English academic painter of genre and historical scenes who is best remembered as the designer of the first ever Christmas card. This specialist of Victorian domesticity painted A Pleasant Corner in 1865 in which a meek domestic and domesticated female beauty is introduced. The young lady is sitting next to the hearth of the house, echoing Tennyson's dichotomous description of gender roles at the time “Man for the field and woman for the hearth / Man for the sword and for the needle she” (1965, 245). The warming heat of the hearth is paralleled by the multifarious nuances of red that can be found in the canvas: the bricks, the tiles, the tapestry, the curtain, the dress and the rosy cheeks of the woman are subtly connected by this chromatic fusion. The curtain slightly drawn gives the viewer the impression of being introduced into the sacrosanct space of domestic intimacy to discover a lady reading a book whose content is impossible to guess. Obviously, one might wonder if the girl's cheeks are only warmed by the presence of the fire in the hearth next to her or if they are also burning because of the content of this mysterious book... Yet, a reassuring clue is given about the innocence of this young lady thanks to the presence of a white flower delicately placed on her lap: a snowdrop which ostensibly comes from the bunch of flowers in the vase situated on the windowsill. In literature and art, snowdrops are one of the plants used as a symbol of purity and innocence. The white colour of these earliest of flowers is often associated with such qualities and the delicate and fragile appearance of the blooms is thought to evoke feelings of tenderness and vulnerability, bringing to mind another poem by Tennyson entitled “The Snowdrop”:

Many, many welcomes,February fair-maid,Ever as of old-time,Solitary firstling,Coming in the cold time,Prophet of the May time,Prophet of the roses,Many, many welcomes,February fair-maid! (168)

The snowdrop, defined by Tennyson as “February fair-maid” and the young maid are both associated with bringing warmth and comfort in the cold times. The book that this young lady is holding is therefore meant to be reassuring: even if we are intruding on this private space in a solitary moment, the lady is reading a respectable book and seems to be crowned by a white luminous blossom in the tapestry above her head as if it were a form of blessing from the painter and, indirectly, Victorian society.

This painting seems to be the perfect illustration of the pure and limited relationship between women and knowledge that was expected in Victorian times. One may quote, for example, the recommendations drafted by John Ruskin, a renowned art critic of the Victorian period, in his essay Sesame and Lilies that constrained women's thirst for knowledge:

All such knowledge should be given her as may enable her to understand, and even to aid, the work of men: and yet it should be given, not as knowledge, - not as if it were, or could be, for her an object to know; but only to feel, and to judge. It is of no moment, as a matter of pride or perfectness in herself, whether she knows many languages or one; but it is of the utmost, that she should be able to show kindness to a stranger, and to understand the sweetness of a stranger's tongue: It is of no moment to her own worth or dignity that she should be acquainted with this science or that; but it is of the highest that she should be trained in the habits of accurate thought; that she should understand the meaning, the inevitableness, and the loveliness of natural laws; and follow at least some one path of scientific attainment, as far as to the threshold of that bitter Valley of Humiliation, into which only the wisest and bravest of men can descend, owning themselves for ever children, gathering pebbles on a boundless shore. (1919, 113-14)

Women are thus limited to the realm of emotions, of feelings, an intellectual hortus conclusus that condemns them to the domestic sphere, to the restricted knowledge relating to the house and its economy and, more importantly, to the knowledge of natural wifehood and motherhood.

2. A warning against unwanted female curiosity

It comes as no surprise that very few representations of female scientists or women engrossed in intellectual study are to be found in the Victorian period. Yet, many literary or mythological representations of female heroines were created at the time in order to warn against female curiosity, which could also be viewed as a form of desire for intellectual exploration leading them beyond the acceptable limits defined by Ruskin.

In 1862, Edward Burne-Jones went for a short visit to Italy with his wife Georgiana and John Ruskin. When he came back, he decided to represent Fatima, Blue Beard's last wife who is often depicted as a nosy young heroine. To do so, he drew on two sources: Les Contes de ma mère l'Oye (1690) by Charles Perrault and the play entitled Blue Beard or Female Curiosity (1798) by George Colman and Michael Kelly ((The play sets the story in Turkey, hence the name of the painting, Fatima.)).

Burne-Jones did not focus on the bloody discovery of all the corpses in the forbidden room but on the fatal gesture of Fatima opening the door. The dark corridor and the small door in the background suggest Fatima's rush to the room and her untamed desire for knowledge while her husband is away. She is still holding the bunch of keys she was entrusted with by Blue Beard himself. Her right hand is turning the key in the keyhole and her eyes staring straight at the viewer show her determination to know what is hidden behind the locked door, no matter the risk she is taking. The orange hues of her dress, whose shape and colour were inspired by Burne-Jones's stay in Venice and his discovery of the Renaissance masters, could be viewed as the projection of the bloody content of the forbidden room and a warning against the potential danger of unwanted female curiosity.

Another female figure who was often used to depict this lethal curiosity was Pandora, who inspired Dante Gabriel Rossetti in 1871 and 1878, and later on John William Waterhouse. The latter's Pandora appeared in the Academy exhibition of 1896 and ushered in the kneeling pose of the model which inspired many of the artist’s paintings.

An obvious link can be drawn between this Pandora and Psyche, which John William Waterhouse painted in 1903, as both pictures stage a woman incapable of resisting the call of curiosity even if, of course, the size of the box is slightly different. This can be explained by the fact that Pandora's box is supposed to contain all of humanity's sins whereas in the case of Psyche, there is a more personal dimension to the story since it is limited to her love for Cupid. As Anthony Hobson summarises:

Psyche shares Pandora's curiosity, but her problems are of a more individual nature. Her name literally means the breath of life, but since she also personifies the soul, finding its immortality after many trials, the psyche itself has been appropriated by modern science as its equivalent. In the legend, she is a maiden so lovely as to arouse the envy of Venus, who sends Cupid to couple with her with the vilest of mortals in revenge for her beauty. Cupid falls in love with her himself, takes her to his palace, and visits her only by night, forbidding her to seek his identity. However, when she disobeys and lights a lamp to gaze on him, a drop of hot oil falls from it and awakens Cupid. He leaves her in anger, the palace vanishes, and in the hope of winning him back she undertakes a series of perilous or apparently impossible tasks set by Venus. One of these is to bring back the box from Proserpine in Hades. (1989, 85)

Clues are added to both paintings to enable the viewer to differentiate Psyche from Pandora. Psyche can be recognised thanks to the lamp placed on the left: the flame symbolises her eternal love for Cupid. The owls carved on the box embody the spirit of sleep, Hypnos, escaping from it. In the case of Pandora, the large size of the box reminds us that it was a present given by Zeus to Pandora when she was supposed to become the bride of Epimetheus, the brother of Prometheus. As Anthony Hobson argues, this box is to be interpreted as both a gift and a curse (1989, 85) and its rich gilded decoration is only to be contrasted with the evils that can be seen escaping on the left. Yet, beyond the differences that can be pinpointed, similarities between the two stagings of female curiosity can be found. In both canvases, the viewer is shown a seductive young lady whose inability to resist the temptation of knowing what is forbidden is anchored in a bodily representation of this unquenched desire. In the two paintings, the half-naked female body reveals a sensual left shoulder. What's more, both scenes are taking place in a gloomy forest as if the painter was trying to foreshadow the terrible consequences that can result from a woman's inability to tame her curiosity, her unconscious (or conscious?) desire to know maybe about desire itself.

3. Women's “unnatural” thirst for knowledge

Female curiosity is regularly presented as the source of deadly consequences not only for women, but, in the case of Pandora, also for mankind in general. Therefore, women's thirst for knowledge, no matter its motivation, is depicted as unnatural, even more so in the case of the representations of prophetesses of all sorts.

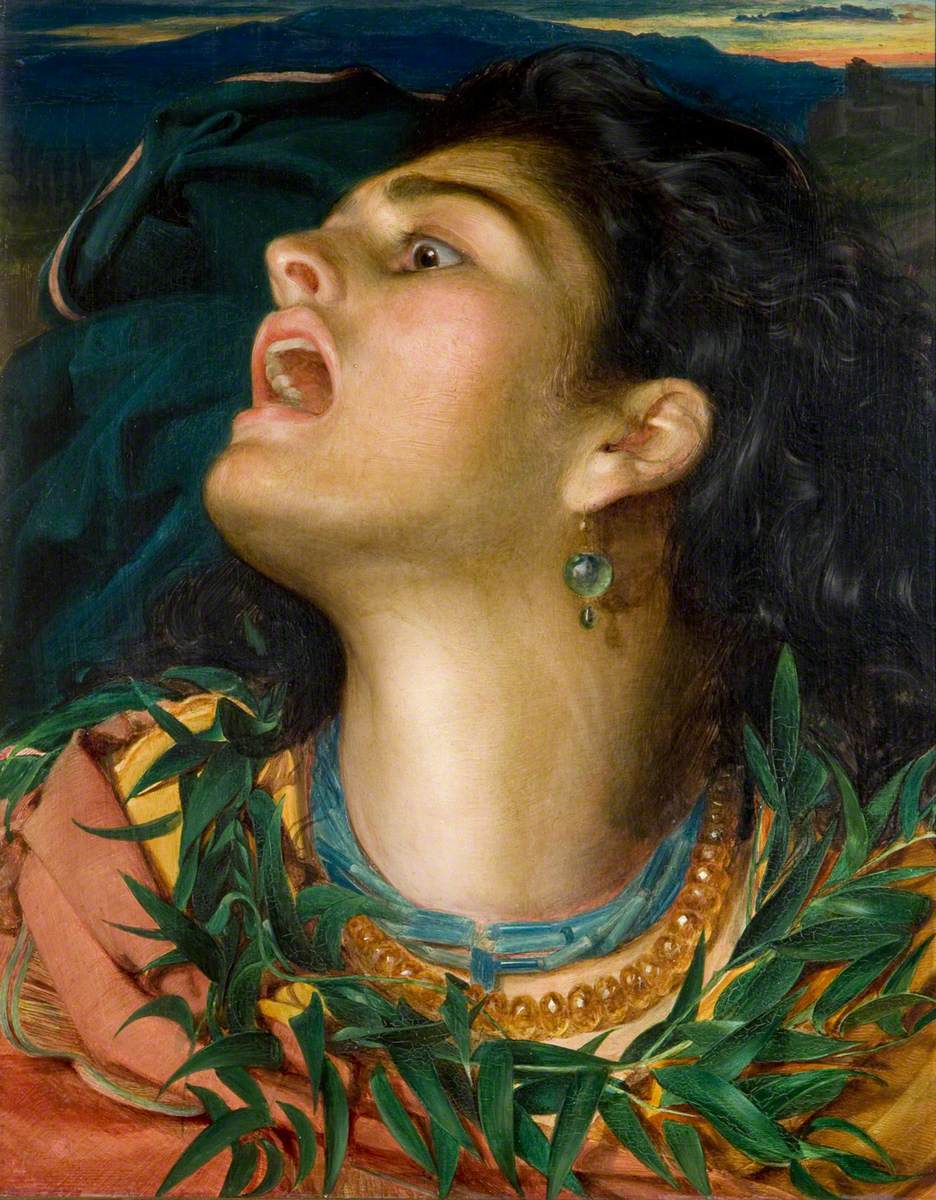

A frightening depiction of women's capacity to foretell the future is shown in Cassandra (1863-64) by Frederick Sandys. Cassandra was the daughter of Priam, the king of Troy: she prophesied the Greek invasion of the city but no one listened to her. After the fall of Troy, she was taken as a slave to Greece, and murdered there. The model used for Cassandra was presumably Keomi, Sandys's lover who drove him to near personal and professional catastrophe by granting or depriving him in turn of inspiration. This oil painting depicts a young brunette whose head is ominously turned to the left. Her eyes and her mouth are wide open like an open wound and suggest the threat that female knowledge might constitute for the prophetess herself. The dismal landscape in the background offers a dark echo to the cry uttered by Cassandra. The suffering and despair linked to her future murder might even be read in the saturated repetition of the tear-shaped drop in her yellow necklace and her blue earring. The superposition of her necklaces and her wreath of leaves, far from crowning her superior knowledge, seems on the contrary to strangle her.

The unnatural dimension of women's thirst and quest for knowledge is also conveyed by representations of the savage nature of the prophetess, often associated with wild beasts. For instance, in The Tiburtine Sibyl (1875) Burne-Jones insists on her link with the sylvan world since this locus on the margin of Tivoli was the place where she was supposed to deliver her oracles.

Her feral dimension is made obvious by her wearing an animal skin. This chalk and pencil drawing is very different from the fresco dedicated to the representation of the Sibyl painted by Michelangelo in the Sistine Chapel – a fresco that Burne Jones admired at length during his third journey in Italy in 1871 – in which the Sibyl is presented as a solid embodiment of civilised knowledge. On the contrary, the gravitas of Burne-Jones's Sibyl reveals how she seems to be plagued by her gift for divination and the unnatural association between female nature and knowledge. She stands in sharp contrast with the meek and humble representation of the Virgin Mary and Jesus Christ on Mary's lap in the background: it seems that the Virgin embodies an unreachable femininity for the Sibyl condemned to live on the margins of society because of her superior knowledge. The same wild identity is ascribed to the prophetess / the sorceress imagined by John William Waterhouse in The Magic Circle (1886): the gypsy-like prophetess is surrounded by crows and the animal dimension of her power seems to slowly contaminate her identity with her jet-black hair recalling the blackness of the feathers of the crows, but also with her dress on which a warrior and, more importantly, a red bird are woven. This scene seems to take place somewhere in inferno with a devilish priestess conjuring up dead spirits in front of the toad added in the right-hand bottom corner of the painting.

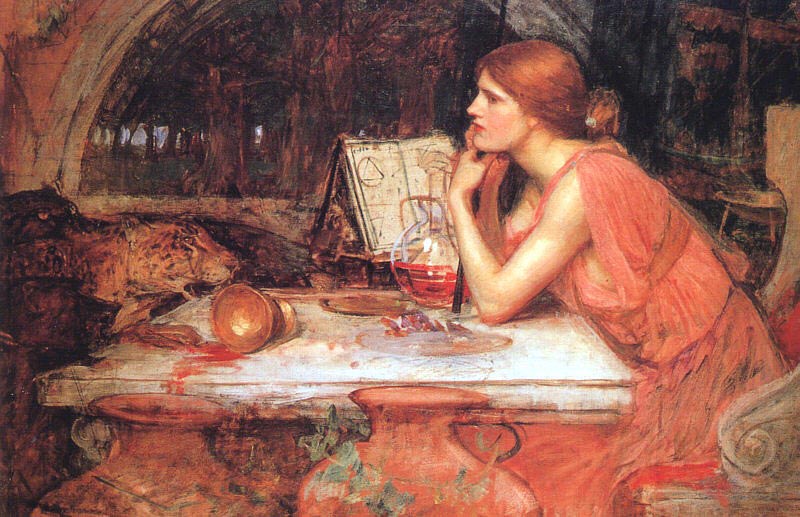

4. Fearing the castrating figure of the sorceress / of female power

The Magic Circle by John William Waterhouse subtly reveals the latent Victorian fear of the castrating figure of the sorceress. In another painting explicitly entitled The Sorceress (1911), Waterhouse created a dual portrait with, on the right, an attractive Femme Fatale offering her venomous beauty to the bewitched eye of the beholder. In a symmetrical disposition, blood-thirsty wild beasts seem to be a mirroring image of the sorceress, revealing the real nature of her tempting flesh. The spell-book in the very heart of the picture acts as the axis of symmetry that turns the woman into a devastating animal spreading blood all over the table. Blood pervades the whole picture thanks to the red colour that emerges from the woman's armchair and dress. The latter, far from hiding her essence, on the contrary lifts the veil on her real devastating capacity.

In Morgan Le Fay (1863-64) by Frederick Sandys the figure of the sorceress is embodied by king Arthur's half-sister, who was given a prominent position with other Arthurian women in the Arthurian Revival that happened in Britain in the 19th century. Morgan is a learned and crafted sorceress who uses her Machiavellian intelligence and knowledge of the dark arts to try to wreak havoc in the kingdom. Once again, Sandys ascribed to this woman an animalistic dimension since she is donning a leopard skin and a yellow dress upon which many cabbalistic symbols (including a snake and a dragon) suggest her beast-like cruelty. Her dark knowledge is also symbolised by the owls that can be spotted directly above her head and on the Egyptian tapestry in the background upon which Horus's and Anubis's heads can be discerned. She is trampling scrolls and books of knowledge displayed in the foreground. She has used ancestral medical transmission to mix this knowledge with her black art, as symbolised by the Hindu chandelier and the fire burning in the brazier in the background, which in turn finds an echo in the setting sun, as well as by the half open cupboard on the left which only suggests the depth of her hidden knowledge instead of revealing it. The fierceness of her gaze crowned by a frowning redolent of Caravaggio's portraits speaks volumes about her cruel determination. Indeed, Morgan has woven a cloak as the loom on the right indicates, a cloak that she intends for king Arthur, her half-brother. She is now adding the final touch to her deadly present as she is poisoning the cloth thanks to a burning instrument once again shaped like an animal. Sandys may suggest here that knowledge can be turned into a deadly burning weapon if it escapes men's wise supervision...

The same interpretation can be made of the revival of another Arthurian character, Vivien, also called Nimue depending on the literary tradition used. The Beguiling of Merlin (1873-74) enabled Edward Burne-Jones to make a triumphant public return to the Grosvenor Gallery in 1877.

The face that was used to represent Vivien was that of Maria Zambaco, Burne-Jones's favourite sitter and lover. Burne-Jones himself identified with Merlin because of the bewitching power that Maria had on him and his artistic creation. Nimue is depicted as a learned woman holding the book of knowledge that she has stolen. Indeed, she seduced Merlin promising the wizard love in exchange of his knowledge and the unfortunate result of this pact is suggested by the position of the two characters: Merlin is languishing in a passive, abandoned horizontal position on the brink of being swallowed by the hawthorn bush that Nimue is going to use to get rid of this cumbersome dotting lover... As for Nimue, she is the one standing in a central and domineering position and the downward gaze that she directs onto Merlin suggests her petrifying sway over the old wizard. Nimue in this canvas is represented as an obvious resurgence of Medusa, the castrating female figure by excellence, as several clues reveal: the mannerist serpent-like shape of her body, the twirling trunks of the hawthorn bush, the drapery of her cloth and finally her serpentine head-dress. Merlin has been deprived of his knowledge and is condemned to eternal sleep as the irises in the foreground foretell – Iris being the messenger of Hypnos in Greek mythology. The moral of the story is therefore double: men should be wary not to fall victim to their desire and should resist female bewitching attraction, and knowledge should be kept out of women's grasp since otherwise it is bound to wreak havoc.

In Medea (1868) by Frederick Sandys, the same reference to Medusa can be found but used in a subtler way. Naomi, Sandys's sitter and lover, embodies the threatening witch who was able to murder her own children when Jason – the conqueror of the Golden fleece that can be spotted in the background of the tapestry – left her for the daughter of the king of Corinth.

In spite of the ironical presence of cranes - the symbols of eternal love in Japan, whose artistic influence can be found in the canvas - Jason's departure is recalled by the ship of the Argonauts leaving on the left and this betrayal accounts for Medea's frowning gaze and fierce determination. The bloody project of this abandoned wife and mother is suggested by the self-mutilating gesture of her hand: she is about to use her knowledge in the occult to destroy her own flesh and blood and thus avenge herself on Jason. Deadly symbols are scattered throughout the painting: all of the instruments of witchcraft are linked by a red thread in the foreground, twisting the traditional Renaissance framing of the gentle Donna alla finestra usually presented behind a parapet. In the background frieze, cobras, Egyptian gods with animal heads, beetles and owls – Lilith's sacred animals – are all echoes of the power of destruction of the dragon – the keeper of the Golden Fleece – crouching behind Medea, both ready to pounce upon their victims. Like in almost all of Sandys's representations of Femmes Fatales, the heroine is wearing a coral necklace that reminds us of a conglomeration of blood-drops. The choice of coral subtly creates an archetypal link with Medea. Indeed, in book four of the Metamorphoses by Ovid, the author says that it is through the contact of Medusa's blood with the sea water that coral was born:

Mean-time, on Shore triumphant Perseus stood,And purg'd his Hands, smear'd with the Monster's Blood:Then in the Windings of a Sandy BedCompos'd Medusa's execrable Head.But to prevent the Roughness, Leafs he threw,And young, green Twigs, which soft in Waters grew,There soft, and full of Sap, but here when lay'd,Touch'd by the Head, that softness soon decay'dThe wonted Flexibility quite gone,The tender Scyons harden'd into Stone.Fresh, juicy Twigs, surpriz'd, the Nereids brought,Fresh, juicy Twigs the same Contagion caught.The Nymphs the petrifying Seeds still keep,And propagate the Wonder thro' the Deep.The pliant Sprays of Coral yet declareTheir stiff'ning Nature, when expos'd to Air. (1727, 129)

Sandys's fascination with threatening, frowning sorceresses can also be explained by his own fascination for the Caravaggio-like representation of Medusa that he drew at least three times. This petrifying figure is a good visual summary of the castrating power that was associated by male artists in Victorian times with learned women / artists who were capable of depriving men of their intellectual domination in order to serve their own unnatural quest for knowledge and thus independence.

The male Pre-Raphaelite artists elaborated a unidimensional representation of the relationship between women and knowledge, condemning learned women to the role of mere castrating witches. It is time to redress the wrong done to Victorian women and shed light on the close link between women and artistic or intellectual creation by focusing on the Pre-Raphaelite sisters, as Jan Marsh invites us to do:

It would be disingenuous to ignore the fact that Pre-Raphaelite art was overwhelmingly made by men in male-dominated studios, or that male artists' reputations, created by male patrons and critics, similarly commanded the historical record. But it is equally mistaken to ignore women's agency and present the female presence as the aesthetic equivalent of the bowl of fruits or flowers. (2019, 8)

SEE PART 2 (Pre-Raphaelite artists' female perspective)

Notes

Works Cited

Paintings

BURNE-JONES, Edward. 1872-1877. The Beguiling of Merlin. Lady Lever Art Gallery, Port Sunlight (GB), oil on canvas, 186 cm x 111 cm.

---. 1862. Fatima, Bluebeard’s Wife. Private collection, pencil, watercolour and bodycolor on paper laid on canvas, 78.7 cm x 26.7 cm.

---. 1875. The Tiburtine Sibyl. Private collection, pencil, black chalk, and coloured pastel, heightened with gold paint on paper, 111.6 cm x 45.3 cm.

CALCOTT HORSLEY, John. 1865. A Pleasant Corner. Royal Academy of Arts, London, oil on canvas, 76.2 x 55.9 cm.

MICHELANGELO. 1508-1512. The Delphic Sibyl. Sistin Chapel, Vatican, fresco.

SANDYS, Frederick. 1863-64. Cassandra. Ulster Museum, Belfast, oil on board, 30.2 cm x 25.4 cm.

---. 1868. Medea. Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery, Birmingham, oil on canvas, 61.2 cm x 45.6 cm.

---. c.1875. Medusa. Victoria and Albert Museum, London, black and red chalks on greenish paper, 72.7 cm x 54.6 cm.

---. 1864. Morgan Le Fay. Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery, Birmingham, oil on wood panel, 61.8 cm x 43.7 cm.

WATERHOUSE, John William. 1886. The Magic Circle. Tate Britain, London, oil on canvas, 183 cm x 127 cm.

---. 1896. Pandora. Private collection, oil on canvas, 152 cm x 91 cm.

---. 1903. Psyche. Private collection, oil on canvas, 117 cm x 74 cm.

---. 1911-1915. The Sorceress. Private collection, oil on canvas, 76 cm x 110.5 cm.

Books

BARRINGER, Tim, ROSENFELD, Jason and SMITH, Alison. 2012. Pre-Raphaelites. Victorian Avant-Garde. London: Tate Publishing.

HOBSON, Anthony. 1989. JW Waterhouse. London: Phaidon Press Limited.

MARSH, Jane. 2019. Pre-Raphaelite Sisters. London: National Portrait Gallery.

OVID. 1727. Translation GARTH, Samuel, DRYDEN John et al. Ovid's Metamorphoses in Fifteen Books. Dublin: S. Powell.

RUSKIN, John. 1919. Sesame and Lilies. London: George Allen and Unwin Ltd.

TENNYSON, Alfred. 1965. “The Princess” in Tennyson’s Poems (vol 1). London: Everyman’s Library.

TENNYSON, Alfred. 1889. “The Snowdrop” in Demeter and other Poems. London, Macmillan.

Pour citer cette ressource :

Virginie Thomas, Images of Erudite Femininity: Capturing the learned/knowledgeable woman in the 19th-century visual arts (part 1: Pre-Raphaelite artists' male perspective), La Clé des Langues [en ligne], Lyon, ENS de LYON/DGESCO (ISSN 2107-7029), novembre 2023. Consulté le 12/02/2026. URL: https://cle.ens-lyon.fr/anglais/arts/peinture/images-of-erudite-femininity-part-1

Activer le mode zen

Activer le mode zen