Images of Erudite Femininity: Capturing the learned/knowledgeable woman in 19th-century visual arts (part 2: Pre-Raphaelite artists' female perspective)

This article is based on a paper given at a conference entitled "Women and Knowledge in 19th century Britain", organised by Virginie Thomas at Lycée Champollion (Grenoble) on the 24th of May 2023. Other presentations included:

-

A voice and a place of one’s own: women, knowledge and empowerment in Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre (Christine Vandamme)

-

“Captives of ignorance” ? Women, education and knowledge in the Victorian period (Véronique Molinari)

-

Images of Erudite Femininity: Capturing the learned/knowledgeable woman in the 19th-century visual arts (part 1: Pre-Raphaelite artists' male perspective) (Virginie Thomas)

Introduction

The representation of cultured women by 19th-century female artists slightly differs from the productions of male painters which Virginie Thomas examined in the first part of this paper. In my own part, I will try to underline the similarities between these representations by male and female painters but also highlight the differences that exist in the vision of cultured women that are taken from men’s paintings and reused in works by women artists. Two major points have to be taken into account when it comes to the way female artists represented learned women. Firstly, women artists knew the paintings of their male counterparts and necessarily took some of their ideas from this iconography of sorceresses and evil women in order to create their own fictive representation of knowledgeable women. Secondly, female artists were differently concerned by the theme of knowledgeable women because when they were painting learned women, they were also to a certain extent representing themselves. Indeed, female artists ‘owned’ a sort of knowledge, namely the artistic skills that enabled them to create works in which they chose to represent learned women. Therefore, female artists were necessarily involved in the iconography of erudite women, for their works could be interpreted as a metaphorical depiction of their own possession of knowledge.

This article will focus on three ways in which learned women were represented and will suggest echoes with a number of paintings which have already been explored in the previous part. The first form of representation is that of cultured women as they go about their everyday lives, this form illustrates the types of knowledge women had the right to claim in Victorian society. The second group includes paintings that show the way in which feminine knowledge was / became associated first with power, and then with madness. Any woman in possession of knowledge had to be frightening because she exceeded ‘female nature’ or what was perceived as her ‘essence’ as a fragile and naïve creature. The final type is significantly less widespread, mainly because male artists never showed learned women this way: it is the representation of women as professionals in scholarly domains.

1. The knowledge women had the right to access

Female representations of the knowledge to which women had access are quite different from those made by men. Instead of representing accomplished women as wives and mothers, as embodied by the Angel in the House ((The Angel in the House is the archetype of the Victorian feminine ideal. The expression is taken from the title of a poem written by Coventry Patmore in 1854. The poet evokes his courtship of his wife, Emily Augusta Andrews, whom he claims is the ideal woman. That is to say, she has all the qualities to become a great wife and mother: submissive to her husband and selflessly devoted to their children; cultured yet wary of showing off her knowledge.)), women artists more frequently showed working women as seamstresses, lending them an accent of despair, as musicians with an air of melancholy, or as unmarried (and therefore marginalised) women whose only option to earn a living and to be considered as members of the Victorian society was to work as governesses for ‘ideal’ Victorian families. These forms of representation differ from the well-established and joyful women in Victorian homes that can be seen in many paintings by male artists. Their female counterparts tended to stress the fact that it was not easy to reconcile women and knowledge in Victorian society, in so far as knowledge was viewed as part of the exterior male sphere, whereas women’s influence was limited to the interior, domestic sphere. Therefore, women and knowledge were not supposed to be brought together.

Accomplishments such as playing music, reading, or needle-working were deemed part of the education of any well-bred woman. These skills were appreciated in a married woman, and made the unmarried woman desirable. Kate Elizabeth Bunce’s Melody (Musica), one of the artist’s most famous works, offers an allegorical representation of music through the figure of a half-length woman holding an inlaid lute (Marsh, 1988, 132). The elegance of the woman is shown in the refinement of the ornaments of her dress, her necklace, her lute and her mirror. The metalwork in the painting is evocative of the Arts & Crafts movement, associated among others with the polymath William Morris. The mirror on the top of which “Musica” is written is certainly made from the silver jewel-set created by his sister Myra Bunce. Bunce was also an artist (Marsh, Gerrish Nunn, 1989, 123-124), leading to an interesting mise en abyme of female artistic creation.

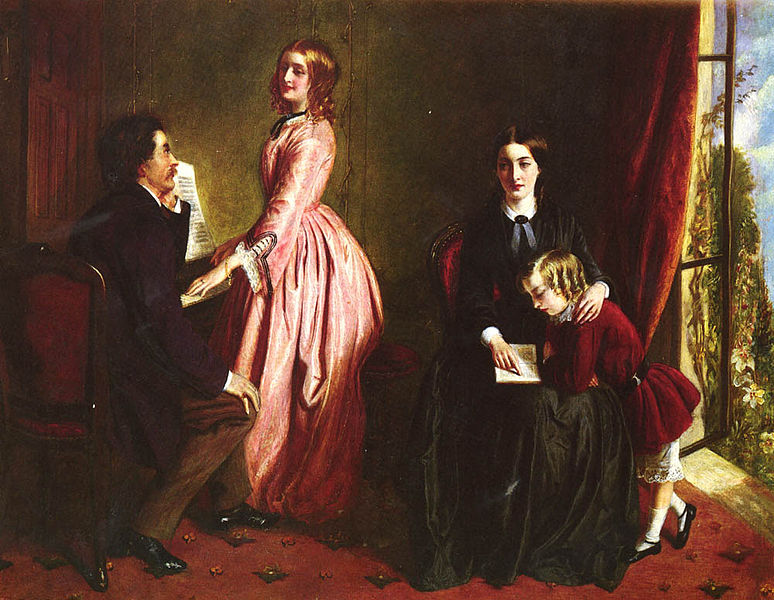

If playing music and reading were skills a suitable wife was supposed to possess, they could also become useful for women who had not found a husband and had to live by themselves. This was the case for governesses. Being a governess was not an enviable place, yet it did enable unmarried women to not be completely marginalised from society. The Governess by Rebecca Solomon, Simeon Solomon's sister, depicts the struggle encountered by governesses. This painting makes a striking contrast between, on the one hand, a girl in pink dress, in the light, rising above all the other characters and, on the other hand, the young woman in a black dress, seated in semi-shade, teaching the young boy, who is glancing with envy at the girl in pink, how to read. The governess figure is nearly the same age as the girl in pink, yet she has a totally different fate. The ornaments of the room indicate the bourgeois social background of this family: the velvet burgundy curtain, the dark red flowered carpet, the matching chairs and stool behind the girl. One can also notice the interior design, with a sort of golden serpentine line entwined around a straight line, which recalls the climbing plant at the window. These ornaments chime harmoniously with the physical characteristics of the blonde girl, who wears a golden bracelet and ring, and an embroidered dress with lace sleeves and neckline. Contrarily, the governess is shown with a simpler dress and hairstyle. Even though she is the eponymous character and therefore supposed to be the main subject of the painting, she is not located at the summit of the composition, but lays in the shade, almost drowned in the burgundy ornaments. The message could not be clearer: the governess is a second-class citizen in Victorian society.

The knowledge to which women and girls had access in Victorian society thus appears to transform them into either idealised creatures, like Bunce’s allegorical feminine figure, or marginalised persons in so far as they needed to work to make a living and as such did not fit into the standard created by men of the idle Victorian woman. They were forced to offer their services to the more fortunate in order to survive, and as a result only existed on the fringes of Victorian society.

2. The frightening prospect of women possessing knowledge

Other illustrations of learned women are less realistic than the ones we have already considered, as female artists also created more imaginary feminine figures associated with knowledge. Given that they could not exist in Victorian society because of all the social rules that restricted women’s lives, these figures were usually drawn from mythology. The theme of Pandora was common to both men and women artists for its universal reach, while numerous sorceress characters were appreciated by 19th-century artists, men and women alike. However, women artists enlarged the scope of these knowledgeable female figures by including mythical warriors.

Sorceresses are a recurrent figure of 19th-century works of art, in part for the ambiguity they embody. Indeed, the sorceress is closely linked to the nature of womanhood, often becoming the incarnation of a masculine fear of women. According to common thinking, if women came to free themselves from male coercion, then they were all bound to become sorceresses! To male artists, a sorceress was both a beautiful enchantress with magical powers and diabolic knowledge linking her to Evil, and a woman who knowingly used her sensual charms to manipulate men’s passions. As a figure of castration - the most frightening personification - she therefore had to be shown as a terrifying figure through her expression, her accessories and her attitude. Women artists seized on this iconography and theme instituted by men and slightly displaced the perspective in order to treat these sorceress figures with greater compassion. To understand the changes women artists applied to the theme of sorceresses, we may focus on two paintings by Evelyn De Morgan, both of which deal with sorceress figures. Medea and Cassandra, who have already been evoked in the first part of this article, are powerful, knowledgeable women drawn from Greek myths who endured tragic fates. While Frederick Sandys painted them with unsympathetic traits, De Morgan used a similar format (a single standing figure) but gave them all the importance of significant individuals.

To begin with Medea, painted in 1889, De Morgan distanced herself from the murderous aspect of the character who killed, among others, her brother, her lover Jason and her two children. She embodies the cruellest woman of Greek mythology because she is considered to be lacking the ‘natural’ and inborn qualities of motherhood. Both of these distorted, abnormal characteristics are linked to the fact that Medea has magical powers and is a priestess of the goddess of witchcraft, Hecate. Such unnatural knowledge drove her mad and made her an evil character, particularly when depicted from the perspective of male artists. Instead of rendering this monstrous aspect in her canvas, De Morgan insists on Medea’s royal status, her dignity and her femininity. Male artists and authors generally underlined her barbarian origins - she is not a Greek princess as she is from Colchis - by depicting her with wild loose hair, a tempestuous personality and uncontrollable temper. Here, her sophisticated hairdressing and robe imply very clearly that she is a cultured and honourable princess. She wears pearls and braids in her hair, and the fabric of her dress is shiny and soft like silk. The setting in which she is depicted is also sumptuous, entirely covered with marble, with an enamelled ceiling, decorated with bronze sculptures, while the stairs are richly ornamented with detailed metal foliage.

Yet in spite of the magnificence of her environment, Medea seems to be imprisoned within it. The checker-board floor suggests that she cannot escape from her murderous fate, just as she cannot break free from the overwhelming architectural framework. This would tend to infer that her evil actions are not only and exclusively her fault. It is nonetheless assumed that she is still responsible, and De Morgan does not entirely absolve Medea of her faults; indeed, the painter highlights that she acted under the decision of gods and the love she had for Jason, as symbolised by the doves and red roses, attributes of Aphrodite, the goddess of love. Her attitude when she faces her destiny is calm, dignified and sorrowful, contrary to the mad behaviour in which Sandys and others depicted her. The viewer sees Medea accepting her fate because she is aware that it is unavoidable, yet she appears not to entirely acknowledge what she is about to do. Although we cannot clearly define which one of her crimes De Morgan is referring to in this painting, the poison vial she holds is reminiscent of the poisoning of the dress of the Corinthian princess who was her rival for Jason’s affections. The way Medea is trying to distance herself from the poison implies her inner disapproval of what the gods forced her to do, but the similar burgundy colour of the poison and of her dress reminds us that she cannot elude responsibility for the murders (Smith, 2002, 100-103; Frederick, 2022).

Doc 3: Medea, Evelyn De Morgan, 1889. Oil on canvas, 148 cm x 88 cm. Williamson Art Gallery and Museum, Birkenhead. Source: The Williamson Art Gallery and Museum.

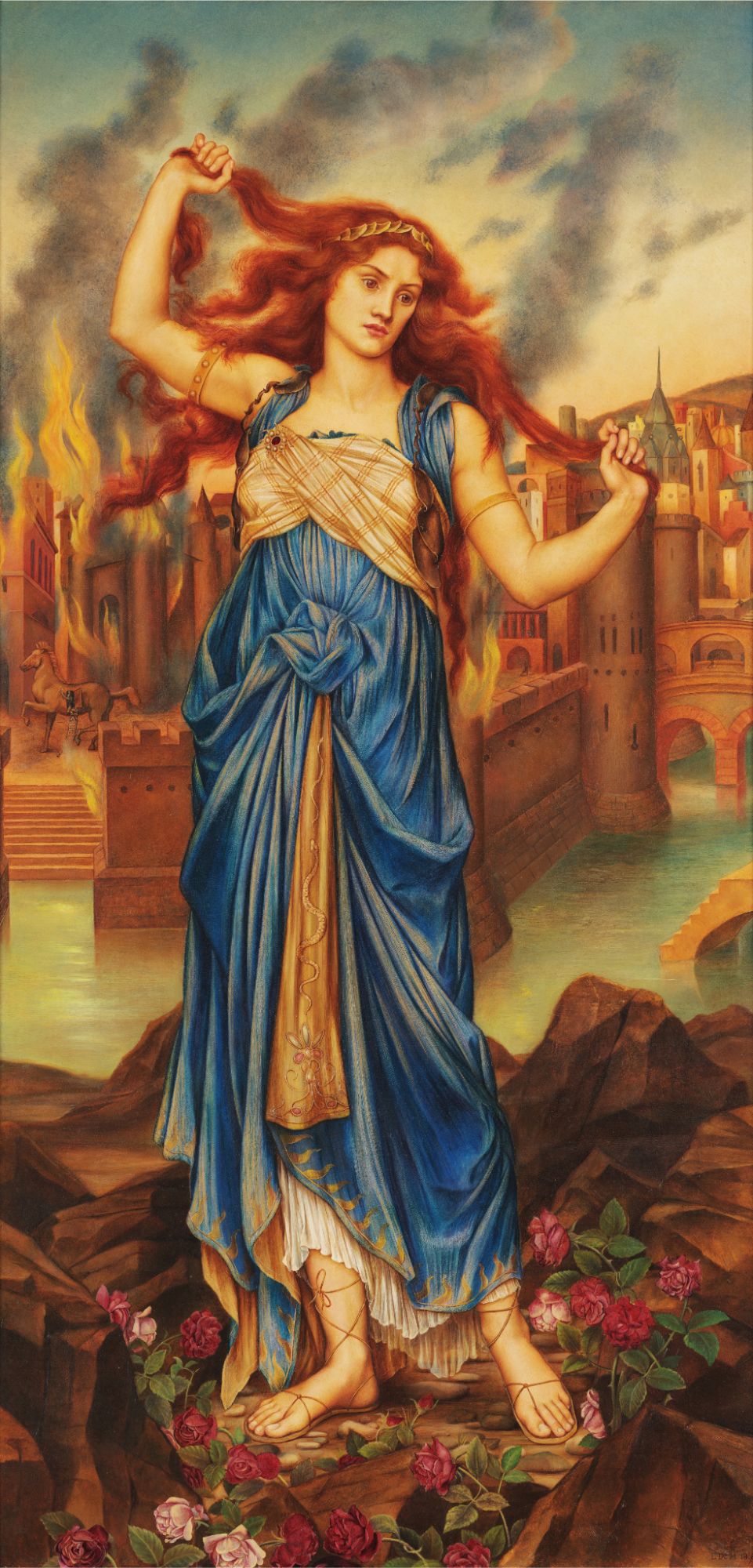

De Morgan also treated her Cassandra with sympathy rather than fear and rejection. Cassandra is a Trojan princess who can predict the future, but she has been cursed by Apollo to be ignored by her peers because she refused to renounce her virginity. Both aspects of her story are depicted in De Morgan’s painting. The stylised gold flames of her dress are redolent of the fire which burns the buildings of Troy, seen in the background behind her. Cassandra did indeed warn the Trojans that the Greeks would invade the city, hidden in a wooden horse, but they did not listen to her. De Morgan pictures the moment not of prophecy, but of invasion: the wooden horse stands in the city of Troy, to the right of Cassandra. Her power of foresight and her virginity are represented by the colour of her gown, a deep blue, which is the colour of the Virgin Mary in Christian iconography, as well as that of spirit and intellect. Therefore, the colour blue references that very purity which led to her being cursed. De Morgan gives a more profound significance to her painting by mixing Greek and Christian references. Cassandra appears powerless, witnessing the destruction of Troy without being able to prevent it. Her despair is depicted through the gesture of pulling her hair, which suggests lamentation in classical iconography. Yet, the rather frightening gesture is compensated by her expressionless face and static pose which provide a striking contrast with the madness we see in the scream shown by Sandys. In this attitude, Cassandra embodies an icon of tragedy because her posture mimics the ambiguity of her character: she is a powerful seer rendered powerless by her curse. This is the reason why she is fixed in place: even though she possesses great power and intelligence, she is silenced by events over which she has no control. It is in this respect that Cassandra can be read as an allegory of the Victorian woman. In fact, Florence Nightingale entitled her 1852 essay about Victorian women Cassandra, implying that the mythological figure is representative of all the potential that such women had but were not given the opportunity to use (Smith, 2002, 92-95).

Sorceress figures were therefore borrowed by women artists from their male counterparts. Yet these female painters also had their own way of representing learned women who were largely ignored by male artists, partly because they did not conform to canonical Victorian beauty. For instance, female warrior figures were an almost exclusively feminine theme. The only example of this type of representation made by men is the character of Joan of Arc, whose portrait was painted by Rossetti in 1882. Although Joan of Arc is usually painted for her holiness rather than for her womanhood, she still is a learned female insofar as she knows the art of fighting. The same goes for a Greek mythical figure named Hippolyta, a heroine known especially in Theseus’ adventures and through the ninth Labour of Heracles. She is represented in the middle of the three-leaf screen created by Jane Morris and her sister, Elizabeth Burden, around 1880, featuring embroidered panels depicting heroines. This embroidered screen was created to decorate the walls of the Red House with images of ‘Illustrious Women’, as a means of paying homage to the poets Chaucer and Tennyson (via a depiction of their iconic heroines). Here Hippolyta appears as the main character, and as such is placed at the centre of the composition. She is fittingly characterised by her strength, as the daughter of two prominent warrior characters of Greek mythology: Ares, the god of war, and Otrera, the queen of the Amazons. She derived her power from the war belt she inherited from her father, and the ninth Labour of Heracles consisted in taking the belt off Hippolyta. This belt is represented by the red string around her waist on the embroidery. The war-like aspect of the character is recalled here through her depiction as a medieval warrior-maiden bearing a sword, a spear, and pieces of armour beneath her tapestried-like dress. She is not presented in what we can call a ‘feminine’ attitude; on the contrary, she holds her weapons as a male soldier would.

Morris and Burden thus create a contrast with the commonly-received idea of the passive medieval damsel (Marsh, 1988, 103). In many representations of women as warriors, the woman is a threat for men because she shows she does not necessarily need them to save and protect her. This could be one of the reasons why male artists were reluctant to paint them as this type of figure. It should be noted however that this embroidered work is sometimes attributed to William Morris instead of his wife and her sister, Elizabeth Burden, thus further begging the question of the recognition of women in craftsmanship. These were skills that they could learn and practice, but which the history of art sometimes subsequently took away from them.

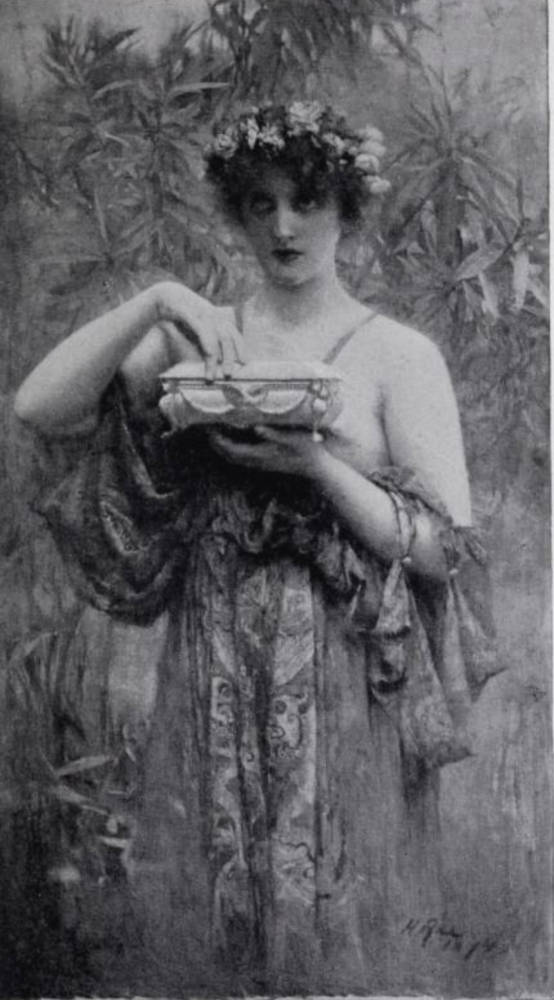

If we consider a final example of so-called ‘unnatural’ associations between women and knowledge in the iconography of 19th-century visual arts, the figure of Pandora is a case in point. Indeed, the myth of Pandora’s box is the original justification for the incompatibility between women and knowledge. In this myth, all of the evil in the world and the pain of humankind is caused by the encounter of Pandora, the embodiment of every woman, with knowledge. The inborn yet ostensibly irrational thirst for knowledge felt by women is therefore considered to be at the origin of all humanity’s sins. In Henrietta Rae’s Pandora, the female figure has not yet opened the box. She still appears as a naïve young woman, shown in all her femininity and sensuality thanks to a robe which does not cover her shoulders and falls on her arms. The delicacy of femininity is likewise depicted through the movement of her fingers. The Pandora figures in works by Rossetti (1871, Private collection) and Waterhouse (1896, Private collection) have already half-opened the box, from which a red or grey fog can be seen escaping, announcing the evil that is to be released. Rae shows the moment just before this, when the woman is still innocent and not guilty of all the evils of the world.

All these mythological feminine figures embody a similar message to the one male artists chose to convey, except that female artists tended to be more understanding than their male counterparts. Female artists also expressed the mitigating circumstances and motivations of the women they painted, so that they could be judged less harshly and treated more sympathetically.

3. The under-representation of scholarly women

Women artists were generally kinder with the figures of learned women because they were, in a way, a representation of their own selves. That also explains why female artists were more likely than their male colleagues to show women as professionals in scholarly domains. Nevertheless, the representations of intellectually active women were almost non-existent in 19th-century British visual arts. This can be largely justified by the reticence of men to paint erudite women, since women were not expected to earn their living thanks to their intellect: they were to be embodiments of beauty, not the mind. Female artists tried to distort this prejudiced vision: they showed women as allegories of Wisdom, while also representing female scientist figures. However, such individuals were already known and accepted by the public, so to this extent were still ‘mythical’ characters.

One depiction of a woman as an allegory of wisdom can be found in a 1912 tapestry by Marianne Stokes entitled Ehret die Frauen (“homage to women”). The sentence stitched at the top of the tapestry is taken from Friedrich von Schiller’s 1796 work Würde der Frauen, which means “Woman’s Worth”. Schiller’s text reads: “Ehret die Frauen sie flechten und weben. / Himmlische Rosen ins irdische Leben” which can be translated as “Honour to the women, who braid and weave heavenly roses into earthly life”. Stokes represents five allegories: from left to right, we can see Courage, Caring or Faith, Love or Madonna, Wisdom and Fidelity. Both Courage and Fidelity are pictured as androgynous male figures, while the three others are clearly feminine characters. It is the fourth one which most retains our attention. The symbols around her express her allegorical significance: she carries a lamp, which symbolises wisdom because it enlightens the darkness of ignorance. The owl behind her back is an attribute of Athena, the Greek goddess of Wisdom, and the book she holds seems to be a primer as one can read the letters “ABC” on the front page (Evans, 2009, 126).

Another allegory of wisdom was depicted by Marie Spartali Stillman in her 1867 painting The Lady Prays - Desire. This portrait is drawn from the character of an epic poem by Edmund Spenser but Spartali chose to modify several of the attributes of this woman whose very name expresses her ambition for glory. In Spenser’s text, the lady holds a poplar branch, but here a book evokes erudition and literacy instead. The laurel leaves she wears in her hair - a classical emblem of Apollo – are a nod to glory in the arts, as well as to the laurel crowns given to victors in poetic competitions in Ancient Greece. To reinforce the prevalence of wisdom over beauty, Spartali added a shield-shaped cartouche in the top left-hand corner of the painting in which we can see an owl holding in its claws a branch with yellow flowers. Under the owl, a gold scroll is visible, bearing a motto written in Greek which could be translated as “Wisdom holds the Spartium”. This underlines the idea of erudition and can be interpreted as a play on the name of the painter, Spartali-Spartium (Gustin, 2020, 11-16).

Doc 8. The Lady Prays - Desire, Marie Spartali Stillman, 1867. Watercolour with gold paint on paper, 41.9 cm x 30.5 cm. Lord Lloyd-Webber’s collection. Source: Meisterdrucke, courtesy of Bridgeman Images France.

The photographer Julia Margaret Cameron went one step further when she chose to embody the savant woman, picturing a woman who was not only a fictional allegory of wisdom but also a thinker and scientist. She took a photograph of Spartali in the guise of Hypatia, an Egyptian philosopher and scientist who taught Neo-platonic philosophy, astronomy and mathematics in 4th-century Alexandria. Her story was brought back to light during the 19th century because of the Neo-Hellenistic movement. Cameron’s photograph was inspired by Hypatia’s life and achievements, but also by a famous novel written by Charles Kingsley and published in 1853: Hypatia; Or, New Foes with an Old Face. Kingsley gave an ambivalent insight into the woman in his work. Indeed, the writer emphasised the anti-Catholic personality of the antique character and presented Hypatia as a beautiful woman in distress, but also with a strong personality and mind. Both of these aspects can be found in Cameron’s work: the beauty and femininity of the long wavy hair falling around her pale face is balanced by her determination, enhanced by the books behind her and the thoughtful glance she casts at something off-camera, which eludes the viewer.

Doc 9. Hypatia, Julia Margaret Cameron, 1868. Photograph, 30 cm x 34.5 cm. Musée d’Orsay, Paris. Source: Site officiel du Musée d'Orsay.

These examples can be considered as the exceptions that prove the rule according to which there are few 19th-century paintings of scholarly learned women. The near absence of representations of women as professionals of knowledge is significant for the period. Indeed, most of the paintings of women we know were produced by men who were reluctant to paint erudite women. Therefore, the few representations that exist were created by women artists. Women were less averse to representing erudite women because they were to a large extent depicting themselves: they owned an artistic technique which they had learned, and they sold the images produced thanks to this knowledge.

Conclusion

Similarities between the representation of learned women made by male and female artists are in fact numerous. They took their inspiration from the same references, images and stories that were prevalent during the same period. Nonetheless, they did not engage identically with the subject of the erudite woman. Men frequently tried to show the incompatibility of women and knowledge and the disastrous consequences such an encounter could create. Women artists had a different approach to the theme: on the one hand, they assimilated these representations but on the other hand, they could not entirely agree with this idea in so far as they themselves were counterexamples of the so-called incompatibility between females and knowledge. A woman artist is by definition a cultured, learned, erudite woman.

This contradiction in the iconography of learned women by female artists is not specific to British visual arts. The entire representation of women and knowledge in 19th-century Western visual arts reveals the same tension. One can think of Marie Bashkirtseff’s 1881 work In the Studio, in which a female group is shown in the Académie Julian in Paris, painting an almost nude model. This painting raises one of the main questions faced by artistic academies in the 19th century. As soon as these schools accepted female students in their classes, they were forced to wonder about the limits of the knowledge accessible to women in their artistic education. Indeed, a great part of the artistic training relied on anatomy lessons and classes during which students drew nude models. There were polemics about the permission or not to allow female students to attend these nude classes. The nearly nude model of Bashkirtseff’s painting is expressing this prohibition female students faced during their artistic training. The debate therefore focused on how to reconcile female artistic education and social respectability.

Notes

Works Cited

Paintings

BASHKIRTSEFF, Marie. 1881. In the Studio. Oil on canvas, 154 cm x 186,1 cm, Dnipropetrovsk Museum of Fine Arts, Dnipro, Ukraine.

BUNCE, Kate Elizabeth. 1895-1897. Melody (Musica). Oil on canvas, 76,3 cm x 50,9 cm, Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery, Birmingham.

CAMERON, Julia Margaret. 1868. Hypatia. Photograph, 30 cm x 34,5 cm, Musée d’Orsay, Paris.

DE MORGAN, Evelyn. 1889. Medea. Oil on canvas, 148 cm x 88 cm, Williamson Art Gallery and Museum, Birkenhead.

---. 1898. Cassandra. Oil on canvas, 124 cm x 73,8 cm, De Morgan Collection, Barnsley.

MORRIS, Jane and BURDEN, Elizabeth. c.1880. Three-fold screen with embroidered panels depicting heroines. Woollen ground embroidered with wool and silk, wooden surround, each panel 135 cm x 71 cm, Castle Howard Collection, York.

RAE, Henrietta. 1894. Pandora. Oil on canvas, size unknown, location unknown.

SOLOMON, Rebecca. 1854. The Governess. Oil on canvas, 66 cm x 86,4 cm, private collection.

SPARTALI STILLMAN, Marie. 1867. The Lady Prays-Desire. Watercolour with gold paint on paper, 41,9 cm x 30,5 cm, Lord Lloyd-Webber’s collection.

STOKES Marianne. 1912. Ehret die Frauen (Homage to Women). Tapestry, 174 cm x 256 cm, Whitworth Art Gallery, Manchester.

Books

CHERRY, Deborah. 2000. « Women, power, knowledge: the image of the learned woman in the 1860s », in Deborah Cherry (ed), Beyond the Frame: Feminism and Visual Culture, Britain 1850-1900. London: Routledge, pp.178-196.

EVANS, Magdalen. 2009. Utmost Fidelity: the painting lives of Marianne and Adrian Stokes. Bristol: Sansom & Company.

FREDERICK, Margaretta S. 2022. Evelyn and William De Morgan. A Marriage of Arts and Crafts, cat. exp. [Wilmington: Delaware Art Museum, 22 October 2022-29 January 2023; California: Crocker Art Museum, 17 September 2023-7 January 2024; Saint-Petersburg: Musée des Beaux-Arts, January-May 2024]. New Haven Conn., London: Yale University Press.

GUSTIN, Melissa L. 14 October 2020. « Wisdom Holds the Spartium: A Closer Look at The Lady Prays-Desire », in Aspectus, University of York, pp.11-16.

MARSH, Jan. 1988. Pre-Raphaelite Women: Images of Femininity. New York: Harmony Books.

MARSH, Jan, and GERRISH NUNN, Pamela. 1989. Women artists and the Pre-Raphaelite movement, London: Virago.

SMITH, Elise Lawton. 2002. Evelyn Pickering De Morgan and the Allegorical Body. Madison, New Jersey: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press.

TAYLOR, Helena Nina. Winter 2011-2012. « “Too individual an artist to be a mere echo”: Female Pre-Raphaelite artists as independent professionals », British Art Journal, vol.12, n°3, pp.52-59.

Pour citer cette ressource :

Agathe Viffray, Images of Erudite Femininity: Capturing the learned/knowledgeable woman in 19th-century visual arts (part 2: Pre-Raphaelite artists' female perspective), La Clé des Langues [en ligne], Lyon, ENS de LYON/DGESCO (ISSN 2107-7029), décembre 2023. Consulté le 08/02/2026. URL: https://cle.ens-lyon.fr/anglais/arts/peinture/images-of-erudite-femininity-part-2

Activer le mode zen

Activer le mode zen