Colonization and koinéization: On the emergence of North American English

Introduction

The following hypotheses, adapted from Trudgill (2004), are often put forward to account for the specificities of North American English, as opposed to English spoken in the British Isles:

- North American English has adapted to its topographical setting, namely to describe new elements of fauna and flora.

- North American English developed thanks to language contact with indigenous languages and non-Indo-European languages (Native American languages, African and Caribbean languages, etc.).

- North American English developed thanks to language contact with other European languages (French, Italian, Dutch, Yiddish, etc.).

- Some linguistic changes occurred in Britain and not in North America (ex: loss of rhoticity, t-glottalization, explained below in 2.1), leading to increased differences between British and North American forms of English.

- Some linguistic changes occurred in North America and not in Britain (ex: t-tapping, the COT-CAUGHT merger, explained below in 3.2), leading to increased differences between British and North American forms of English.

- North America was the stage for dialect ((I will be using the term “dialect” extensively in this paper, especially when referring to the processes of dialect contact and dialect mixture. Dialect is not to be understood as meaning inferior or simplified forms of speech (as is commonly understood outside of the field of linguistics); rather, the term refers to a given linguistic variety that differs from other varieties phonologically, grammatically, morpho-syntactically, and lexically. Dialect should thus be understood as a synonym of “linguistic variety”.)) contact between different varieties of English, leading to forms of dialect mixture.

1. Language contact

1.1 The colonial context

In order to understand the process by which North American English developed, it is important to keep in mind the following historical and geographical landmarks:

- 1565 – Founding of St. Augustine by the Spanish in what is now Florida, the first permanent European settlement in North America ((This, of course, excludes the sporadic Viking settlements of the Middle Ages.)).

- 1607 – After a number of previous failed attempts, the first permanent English colony, Jamestown (Virginia), is founded. This is followed by the foundation of other English settlements on the Atlantic seaboard, such as those of Plymouth (1620), the Massachusetts Bay Colony (1630), Maryland (1634), Rhode Island (1636), Providence (1636), and Connecticut (1636).

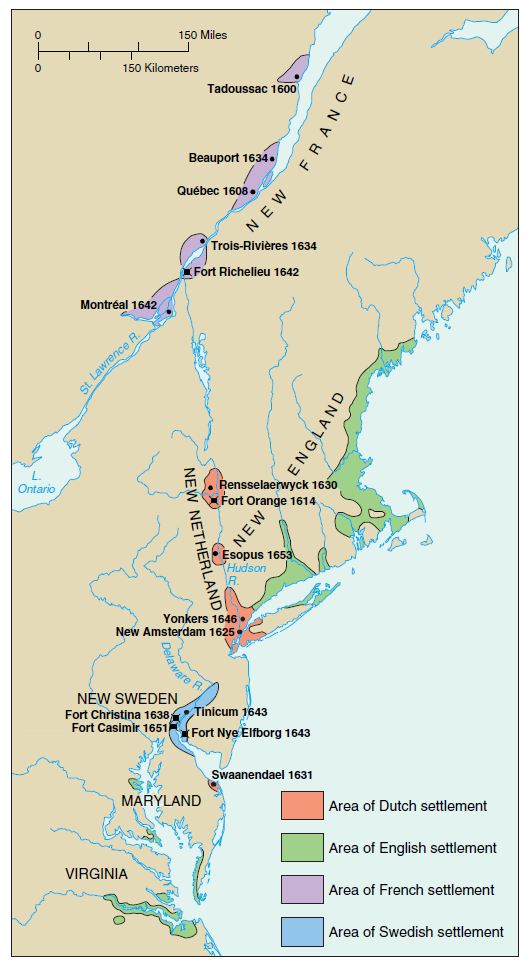

- 1650s – European powers (Spain, England, France, the Netherlands, Sweden) gradually increase their foothold on the north of the Atlantic seaboard (fig. 1.1).

- 1664 – English forces annex the Dutch colony of New Netherland, now New York State.

- 1700 – The population in English-speaking colonies (excluding Native Americans and enslaved populations) is estimated at 260,000 (Calloway, 2013). That number would double in less than 30 years.

- 1703 – The English and their Native American allies destroy the Spanish missionary system in northern Florida, virtually ending Spanish holds on the North-Atlantic seaboard.

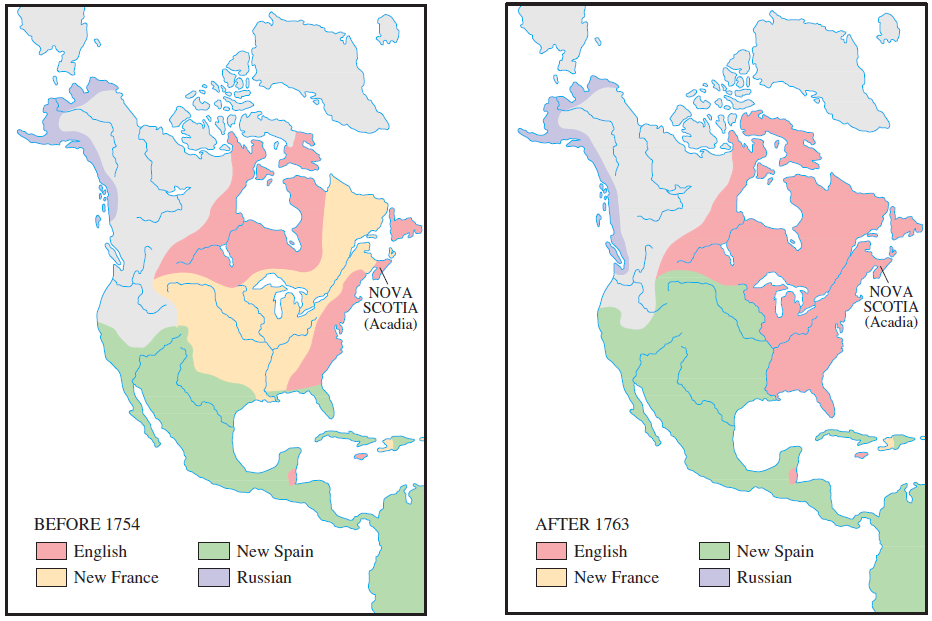

- 1713 – End of Queen Ann’s War (1702-1713). France cedes to Britain the Hudson Bay, Acadia, and Newfoundland; Britain strengthens its hold on the North-Atlantic seaboard.

- 1763 – End of the Seven Years’ War (1756-1753). Britain obtains most French territorial claims west of the Appalachians (fig. 1.2).

- 1783 – Foundation of the United States of America, following the Treaty of Paris.

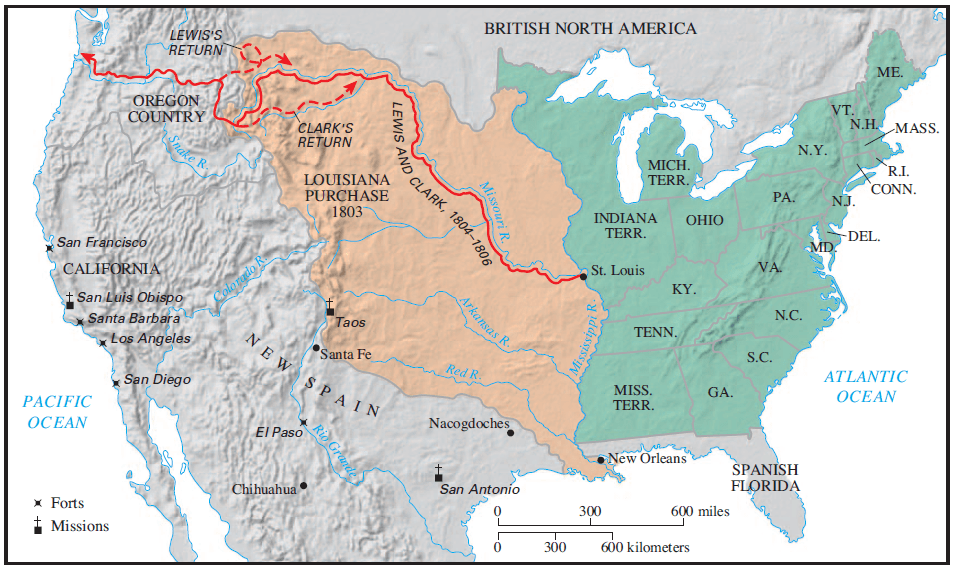

- 1803 – Acquisition of the French territory of Louisiana (the Louisiana Purchase) by the United States government, effectively doubling the area of the young republic (fig 1.3).

- 1830-1850 – Trail of tears: approx. 60,000 Native Americans are forcibly displaced from US states to make way for more settlements inland. This event crystalizes a lengthy tradition of segregation, dispossession, and genocidal massacre of Native Americans by European colonists in North America.

- 1865 – End of the American Civil War. In the wake of the conflict, the former enslaved population is estimated at approx. 3.6 million people, which represents roughly 10% of the total US population (Hacker, 2020).

- 1890 – Declaration of the closure of the American Frontier by the US Census Bureau after decades of territorial expansion. Officially, no tract of land in the US is without settlers.

Despite a strong initial competition between European powers vying for control, and in spite of continuous resistance by Native American populations, England (later Britain) gained control of the North Atlantic seaboard in less than 150 years. These four centuries – and especially the first three – were characterized by the slow political and territorial expansion of English rule, culminating in the complete hegemony of the Atlantic seaboard by the middle of the 18th century (Norton et al., 2008). By the early 18th century, Spain, Sweden, and the Netherlands had been driven out, and by the middle of the century, Britain had a virtually unchallenged hold on that part of the continent. This political dominance was coupled with a strong demographic growth, as half a million colonists could be found in English-speaking colonies by the mid-18th century (Calloway, 2013). The 17th and 18th centuries thus show the consolidation of an English hegemony – meant both as hegemony of the English and hegemony of the English language. The following century shows another major historical feature: the gradual westward expansion of European settlement on the North American continent. Colonists progressively went from the densely-populated Atlantic coast and ventured into the “empty” hinterlands. After centuries of bloody repression of Native American resistance, the initial English-speaking settlements reached the Pacific coast by the end of the 19th century.

The process of colonial expansion, especially in its early stage, was driven by a variety of motives – amongst them economic, political, military, and religious ones (Norton et al., 2008; Mufwene, 2001; Schneider, 2003a). Colonization was propelled by different agents, such as states, business companies, religious communities, missionary and colonization societies, as well as individuals. In particular, the settlement patterns of English-speaking colonies can be summed up into three large types (Norton et al., 2008):

- Northern colonies (Massachusetts, Connecticut, Maine, Rhode Island, etc.): these colonies, often referred to as forming “New England”, consisted initially of a variety of religious communities, especially Puritan (Protestant) colonization societies, which settled in the “New World” ((The expression “New World” corresponds to the Americas from the colonial perspective of European powers: the continent was regarded as a blank slate, as opposed to the “Old World”, free of any past, and fit for European desires of exploitation, colonization, and settlement.)) in the hope of founding religious havens. The harsh climate did not allow for large-scale agriculture. Instead, these colonies consisted of networks of small farms (with indentured slaves), and relied mostly on timber and fishing.

- Middle colonies (New York, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Delaware): these colonies were driven much more by profit, and relied on fishing and trade on a much larger scale, as well as on agriculture. In particular, large coastal cities boomed as trading posts.

- Southern colonies (Maryland, Virginia, North and South Carolina, Georgia): these too were profit-driven, and the warmer climate allowed for the growth of cash crops (cotton, tobacco, and later sugar). The economic structure of these colonies quickly revolved around the slave trade and the development of coastal towns into trading ports.

Such a complex colonization history – especially with so many different protagonists – would seem to suggest that North America witnessed many instances of language mixture or hybridity. In particular, the eastern coast was the stage for language contact

- between European colonists and indigenous populations,

- between European colonists and enslaved populations,

- between different European colonists.

However, in order to understand the outcome of the language contact that occurred in North America, we need to firstly analyze the way in which colonization occurred; that is, the conditions of settlement and the development of English-speaking colonies.

1.2. Indigenous languages and African languages

Mufwene (2001) argues that colonization styles – the particular ways in which new land is colonized – largely define the way language mixture occurs. More specifically, the way colonists settle a land, and the social and political structures that emerge in a colony, determine the interactions between different peoples, and thus define the way different languages combine. Mufwene distinguishes three major types of colonies: trade colonies, exploitation colonies, and settlement colonies. English-speaking colonies in America correspond to settlement colonies. Whereas the first two types are meant to be temporary, settlement colonies are “intended as new, permanent and better, homes than what was left behind in Europe” (Mufwene, 2001, 209) ((Trade colonies are built with the purpose of establishing small trade outposts. Contact with the indigenous populations is limited to rudimentary trade of goods. Exploitation colonies are built solely for the extraction of some natural resources: colonists do not intend to remain and have little interest in developing local roots (Mufwene, 2001).)). Settlers moved to the “New World” due to a variety of pull factors, but mostly in the hope of having a better economic future or in the hope of founding ideal religious communities. Additionally, the cost and the duration of the voyage across the Atlantic meant that going back to Europe was seldom an option.

Settlement colonies – such as the English-speaking colonies – initially saw close interactions with the local population; colonists relied on contact with indigenous peoples for trade and resources, sparking the need to learn some form of local speech. However, given that colonists planned to remain, they were intent on keeping their mother tongues rather than switching to indigenous languages (Mufwene, 2001). Moreover, although settlement colonies favored dialogue with non-Europeans in the early stages, they quickly involved forms of segregation combined with power stratification. Native Americans were continuously pushed back and excluded from the colonial populations, despite some trade and various negotiations with them (Mufwene, 2001). In particular, the local, non-European population, was expected to learn the European language if they wished to be integrated in the colonies. As Mufwene points out, “Europeans had more commitment to seeing their languages prevail as vernaculars (local languages), rather than simply as lingua francas, despite the institution of segregation. Therefore they used them also in communicating with the dominated populations” (Mufwene 2001, 209).

As such, the linguistic influence of Native American languages – in spite of four centuries of contact with European settlers – is minimal, due to particular colonial situations. Native American influence on English is limited to loanwords, which were adopted by European settlers (Mufwene, 2001, Schneider, 2003a; Romaine, 2001; Trudgill, 2004). These typically refer to specifically North American fauna (ex: raccoon, caribou, chipmunk, opossum), flora (ex: pecan, bayou, hickory), cultural elements (ex: tomahawk, squaw, moccasin, potlach) and place names. In particular, one notes a significant number of loanwords from Native American languages to refer to rivers (ex: Mississippi, Ohio), and ironically to place names – given that Native Americans had been forcibly removed – as, for instance, 26 of the US State names are Native American loanwords (ex: Massachusetts, Connecticut, Delaware, Idaho).

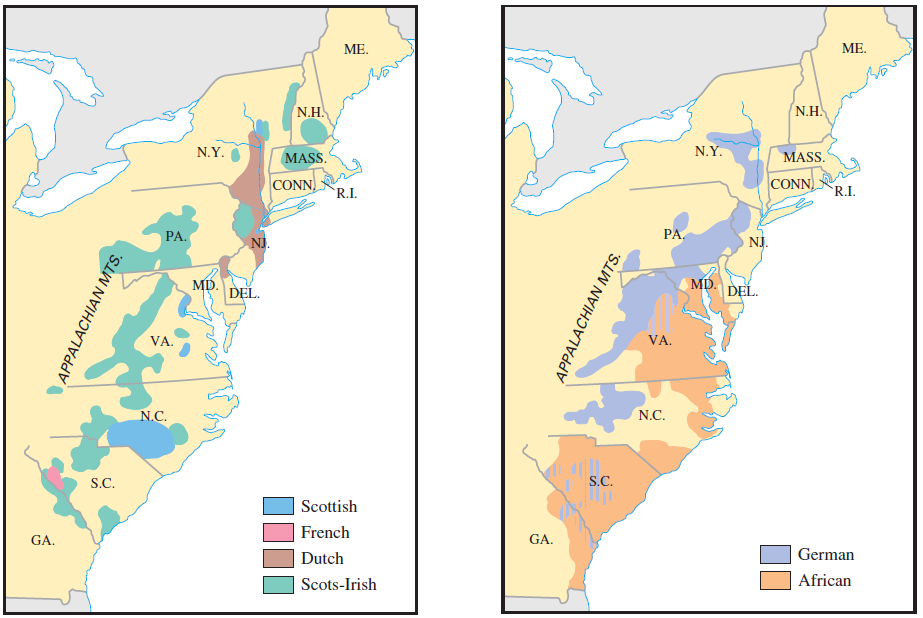

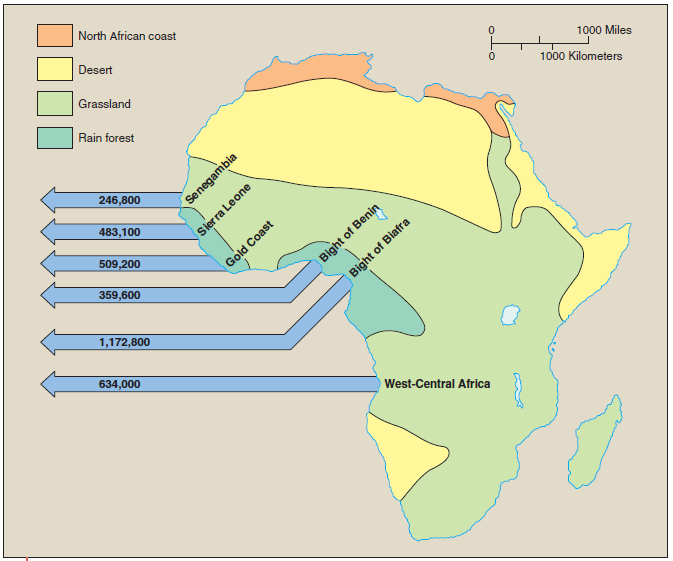

For much of the same reasons, the influence of African languages on North American English is limited to lexical elements – words such as gumbo, bogus, voodoo, banana, or yam (Romaine, 2001; Mufwene, 2001; Trudgill, 2004). The social structure and the power balance at hand greatly conditioned the sociolinguistic interactions between enslaved populations on the one hand, and European colonists on the other. Although many people were forcibly brought from West Africa and the Caribbean as slaves, they were mostly clustered in the colonies that relied on a large-scale plantation economy, hence Southern colonies (figure 1.4). The potential influence of these languages on European languages is thus inexistent in Middle or Northern colonies. In Southern colonies, language contact mostly took the form of a one-way convergence (Giles and Smith, 1979): the enslaved population was expected to adopt the language of the group in power, and not the other way round (Mufwene, 2001).

Additionally, enslaved plantation workers came from many different regions of the west coast of Africa (figure 1.5), and thus often spoke mutually unintelligible dialects or languages (Mufwene, 2001). In such situations, English – the language of masters – became the de facto lingua franca. There was thus very little interest for slaves to keep on speaking a specific African language, since a) they could not communicate with their masters, b) they could not communicate amongst themselves, c) this brought no advancement socially. There thus was an important adaptive advantage to speak the language of masters and African languages virtually disappeared in the next generations (Mufwene, 2001).

There are, however, a few instances of language contact or creolization in the South. In particular, slaves sometimes were used as nannies for the children of wealthy plantation owners, and often spoke to them in their native languages. For instance, in Charleston (South Carolina) the speech of White upper-class speakers shows some phonetic influence from Gullah, a West African language (Baranowski, 2007).

1.3 European languages

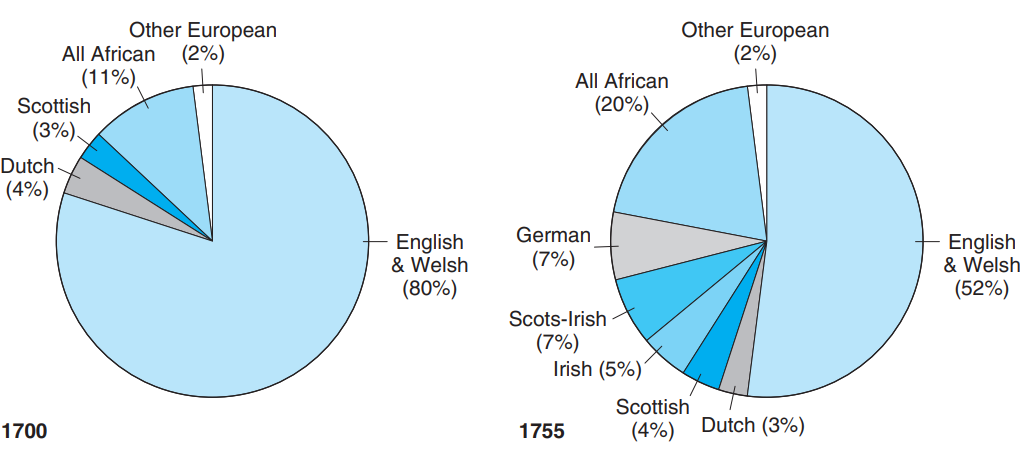

During the early phases of colonization, North America was the stage of a variety of European languages. Between 1630 and 1700, approximately two thousand English settlers arrived in the English-speaking colonies annually, which represented 90% of all European immigrants (Boyer et al., 2011). During the same period, roughly 125,000 German settlers and 100,000 Irish settlers came to these colonies. However, in spite of a large diversity of ethno-linguistic groups (figure 1.4), there were no large-scale instances of creolization (mixture) of English and other European languages. English political hegemony in North America went hand in hand with hegemony of the English language. Apart from the fact that the larger proportion of settlers were initially English speakers, settlement conditions largely determined language contact: these colonies were under English (and later British) rule, meaning that all local political and economic authority was conducted in English.

The territorial and political growth of English colonies coincides with increased contact with other languages. The expansion of English colonies led to the arrival of other ethno-linguistic groups – colonists from annexed colonies, who were integrated as new members of the population. Immigration from non-English-speaking countries continued even when virtually all of eastern North America was under British rule. Additionally, the proportion of African inhabitants – enslaved or formerly enslaved – doubled in fifty years. Figure 1.6 shows the ethno-linguistic groups in English (later British) colonies, between 1700 and 1755. With this situation of increased language contact, many English-speaking colonists were particularly determined to impose English as the language used in the public sphere, especially to conduct political affairs. The French language had some form of prestige, especially in Northern colonies, as it was the language in which Protestant theologian Jean Calvin had written (Romaine, 2001). However, with the arrival of large groups of non-English settlers, colonists were afraid that this could change proportional representations in local governments. As Romaine points out,

the admission of new counties with predominantly French populations changed the representational proportion in the Assembly, some Englishmen asked whether “the Frenchmen who cannot speak our language should make our laws”. (2001, 177)

Similarly, Benjamin Franklin was worried about the influx of German-speaking colonists, and wrote “why should Pennsylvania, founded by the English, become a colony of aliens, who will shortly be so numerous as to germanicize us instead of our anglifying them?” (quoted in Romaine, 2001, 177).

The ethno-linguistic composition of English-speaking colonies shown in figure 1.5 reveals that English speakers initially represented an overwhelming majority of the population. Successive waves of immigration, in spite of eventually outnumbering the original settlers and their descendants, did not modify the local language. This is due to what is known as the founder’s effect (Mufwene, 2001): “the characteristics of the vernaculars of the earliest populations in an emerging colony predetermine the structural features of the resulting variety to a strong extent” (Schneider, 2003a, 241). In other words, the language spoken by founding colonists will remain the dominant language, unless there is a major change in power (conquest, annexation, etc.).

Trudgill (2004) observes that there are more people in the USA today who are descendants of German speakers than there are people who are descendants of English speakers. This has, however, not led to German becoming the language of the colonies, or to German influencing North American English in any considerable way. Likewise, major waves of immigration – from Germany and Ireland between ca 1800 to ca 1870, and from the south of Europe and Slavic countries from the 1890s onwards (Romaine, 2001) – despite “diluting” the original pool of English-speaking settlers, have not affected in any substantial way the original speech of these English-speaking founders, and have certainly not led to a change in dominant language.

Contact with non-English speakers thus did not yield any significant form of language mixture, as the political conditions at hand led to a one-way convergence – non-English-speaking settlers adapting to local social structure and thus adopting the local language. North American English thus corresponds to a variety with an English “core”, from grammatical, morpho-syntactic, phonological, and lexical perspectives. Language contact did, however, lead to the inclusion of several lexical substrates (lexicon). In particular, North American English includes the following lexical substrates that developed in the colonial context:

- Dutch substrate: Santa Claus, biscuit, cookie, boss, Yankee, etc.

- French substrate: lodge, bureau, prairie, chowder, etc.

- German substrate: check, delicatessen, sauerkraut, hex, noodle, etc.

The composition of North American English – and especially its English “core” – raises several questions, since English at the time was not without its own variation and was (and still is nowadays) far from homogeneous.

2. Dialect contact and koinéization

2.1. Language change and variation in Britain

It is not so much language contact as the varieties of English that were brought by colonists that explain North American English specificities. The fourth hypothesis presented in the introduction ((Some linguistic changes occurred in Britain and not in North America, perhaps leading to increased differences between British and North American forms of English.)) is of particular importance, as most features that distinguish British English – and which are thus absent from Northern America – developed before or concurrently with the settlement of North America, and were partially exported to the colonies. Thus, some key “British” linguistic features did not spread, or spread only partially to North America. This means that North American English is not a mere transplantation of English to the “New World” but corresponds, to a certain degree, to a singular configuration of “British” linguistic features.

North America was not settled by colonists coming from a single location: early on, the English colonies welcomed settlers from a wide range of geographical and socio-economic backgrounds. In particular, during the settlement of North America, language in the home colony (England, and to a larger extent Britain) was witnessing profound changes. These changes were not found everywhere, and were not exhibited by all social groups, leading to considerable degrees of geographical and social variation. In particular, the British Isles at the time were undergoing the following changes:

- Loss of rhoticity: the letter “r” is no longer pronounced at the end of words (ex: car) or before a consonant (ex: cart). In dialects that have undergone the change, father and farther are thus now homophones.

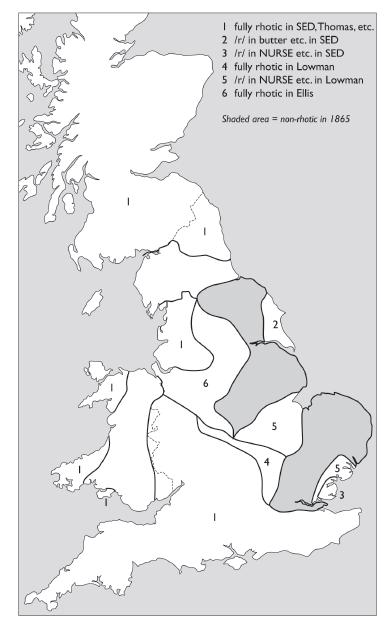

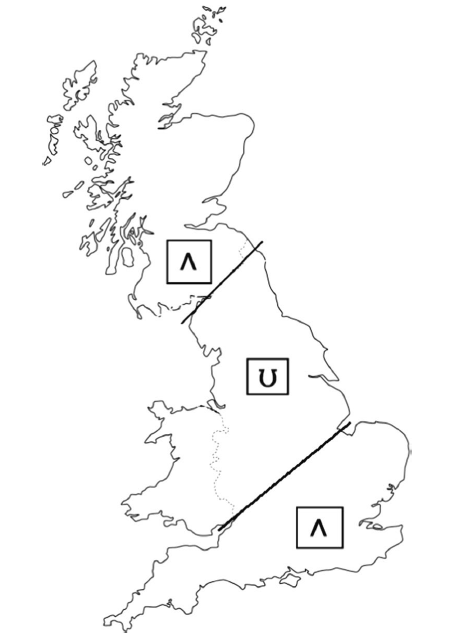

The feature emerged in the southeast of England between the end of the 17th century and the mid-18th century (Trudgill, 2004; Wells, 1982). Loss of rhoticity is now part of standard British English, but persists in many regional dialects, in particular those of Scotland, Ireland, and northern England. Figure 2.1 shows the geographical distribution of rhoticity in Britain.

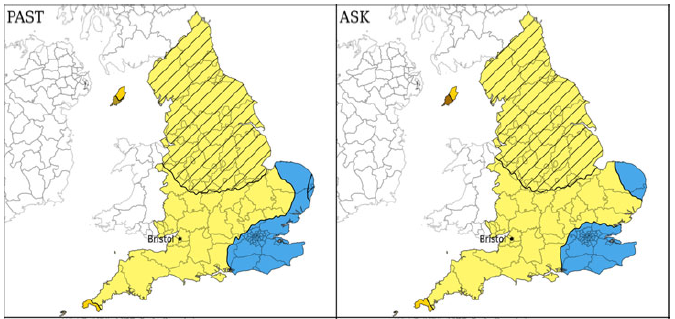

- the TRAP-BATH ((Capital letters refer to lexical sets, which correspond to “set[s] of key words, each of which stands for a large number of words which behave in the same way in respect of the incidence of vowels in different accents” (Wells, 1982, 120). Lexical sets thus consist of words that are realized by speakers with the same vowel sound (which rhyme). For instance, the TRAP set includes the words trap, cat, bat, batter, hat, etc.)) split: words that contain a stressed <a> followed by a voiceless fricative (ex: bath, ass, staff, laugh), a voiceless fricative and voiceless occlusive (ex: wasp, mast, daft), or a nasal and a voiceless fricative (ex: dance, branch, chance) are pronounced with [ɑ:] (and thus have the same vowel sound as in father). In dialects that have undergone the change, these words no longer rhyme with trap.

The feature emerged in the southeast of England in the 18th century and spread to neighboring regions (Wells, 1982; Trudgill, 2004). Figure 2.1 shows the geographical distribution of the split; data are from the 1970s. Blue areas represent the geographical epicenter of the split; yellow areas are where both trap and bath still rhyme. The TRAP-BATH split is now part of standard British English, but spread only partially to the rest of the British Isles, and is to this day notably absent in regional dialects of Scotland, Ireland, and of the north of England.

- the FOOT-STRUT split: words such as cut, bus, strut are realized with a separate vowel (i.e., [ʌ]) and no longer rhyme with foot, bush, book, look. In dialects that have not undergone the change, all of these words rhyme.

The FOOT-STRUT split developed in the south of England in the mid-17th century (Hickey, 2020; Trudgill, 2004; Wells, 1982). Figure 2.2 shows the geographical distribution of the feature in contemporary Britain (/ʌ/ indicates a split of the FOOT-STRUT lexical sets; /ʊ/ indicates an absence of the split). The split is found in the South of England and in Scotland, and is now part of standard British English; it is notably absent in the north of England.

- the Hw-w merger: the word initial digraph wh- (such as in what) is pronounced [w] instead of [hw] (as was historically the case). In dialects that have undergone the change, whine and wine are homophones. The merger developed in the south of England in Middle English (ca 10th-14th centuries) and had become widespread in almost all of England by 1800 (Trudgill, 2004). The merger has also started for present-day speakers in North America. Figure 2.4 shows the geographical variation of the hw-w merger in Britain.

- T-glottalization: the realization of /t/ as the glottal stop [ʔ], intervocalically after stressed vowels (as in better), or word-finally (as in bet) (Wells, 1982). T-glottalization developed in the south of England and in Scotland at the end of the 19th century (Trudgill, 2004). The feature has spread to most areas of the British Isles and is common in casual speech, especially amongst younger generations; it is however still subject to social variation and is often avoided by speakers in formal speech (Badia Barrera, 2015).

2.2. Koinéization

Due to the diverse geographical origins of early settlers, the English-speaking colonies consisted of a mosaic of linguistic features, with the different stages of each sound change. As a result of the linguistic diversity in the British Isles, North America was early on the locus of the process of dialect mixture or koinéization.

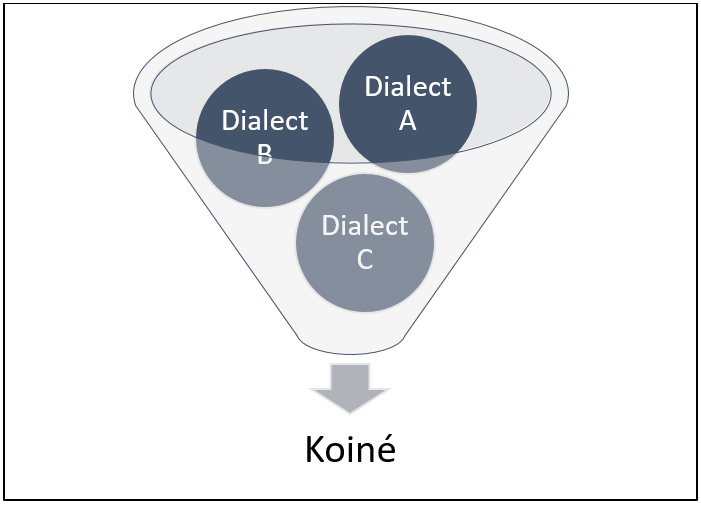

Koinéization consists in the development of an intermediate variety (i.e., a koiné) that arises in a contact situation between speakers of mutually intelligible dialects of a language (Britain, 2012; Mufwene, 2001; Schneider, 2003a; Trudgill, 1986). During the development of colonies, the constant interaction between different English speakers produced routinized forms of accommodation (Giles and Smith, 1979) – speakers unconsciously adapting their speech patterns to match those of their interlocutors. In a couple of generations, this contact setting and confrontation of different features led to a restructuring of English, in the form of a novel configuration of pre-existing linguistic features (Trudgill, 2004). In other words, with the process of koinéization, different mutually intelligible dialects of a language a) gradually become more similar, and b) eventually coalesce into one large encompassing variety, which consists of a unique arrangement of linguistic features. Figure 2.5 shows a schematic representation of koinéization.

It should be noted that this phenomenon occurs specifically in tabula rasa situations (Trudgill, 2004) – that is to say, in settings where there is no prior existing population speaking the language in question. Koinéization is thus typically at hand in colonial contexts (ex: Australia, New Zealand). The fact that this does not occur in already settled areas is due to what is called the founder’s effect (Mufwene, 2001): once a stabilized koiné has developed, successive waves of settlers have a much more limited influence on local speech. In most cases, there is mostly a one-way form of convergence, as subsequent newcomers have to adapt and adopt local speech patterns. Additionally, koinéization only takes place with mutually intelligible dialects; the process did not occur between, say, French and English-speaking colonists.

Dialect contact situations typically consist of a large pool of variants – different realizations of a single linguistic unit – due to the diversity of origins of settlers. Variants can be:

- Lexical: for instance, both a) pail and b) bucket to refer to the cylindrical object used to carry water

- Grammatical: for instance, both a) he isn’t and b) he ain’t, a) haven’t got and b) don’t have, or a) they see and b) they sees

And of particular importance here

- Phonological/phonetic: for instance,

- realization of /r/ as a) [r] or as b) ø in cart

- realization of BATH words (bath, ask, task, etc.) with either a) [æ], b) [a], or c) [ɑ:]

- realization of STRUT words (bus, cut, must, etc.) with either a) [ʌ] or b) [ʊ]

- realization of word initial wh- as a) [hw] or b) [w], such as in which

In each case, the choice of either variant does not lead to any change in meaning. The high degree of geographical variation of English in the British Isles means that depending on the regional origins of settlers, different variants would be present in different proportions in each colony. Koinéization involves the process of leveling (Britain, 2012; Trudgill, 2004) – i.e., the reduction of the number of variants, so that the emerging koiné only has one variant for each item.

The final product (or koiné) is the result of the specific mixture of specific dialects in specific proportions. The elimination process of competing variants is not the result of any conscious choice by speakers, but is due to purely demographic reasons, that is, to the proportion of speakers who exhibit each variant (Dodsworth, 2017; Trudgill, 2004). In other words, a larger proportion of speakers of dialect A leads to a higher proportion of features of dialect A in the ensuing koiné. All English-speaking colonies saw the leveling out of linguistic differences by the process of elimination of minority variants – in the form of variants exhibited by a minority of the population.

In particular, a majority of settlers were rhotic (loss of rhoticity was geographically confined to the southeast of England while the rest of the British Isles were rhotic). As a result, the koinés that emerged through routinized interaction and convergence were overwhelmingly rhotic as well – with non-rhotic variants weeded out, and lack of rhoticity virtually disappearing in a few of generations. Conversely, the hw-w merger had gone to completion in most of England by that time: settlers who pronounced which with [w] thus outnumbered those who used [hw], meaning that the minority variant was rapidly leveled out in the ensuing koiné.

The phenomenon of koinéization also explains the high degree of geographical uniformity in North America (compared to the British Isles). More specifically, another direct consequence of this dialect contact situation – apart from the novel configuration of diverse dialectal features of English – is the emergence of a uniform variety of English in North America, due to the process of koinéization occurring simultaneously all over the Atlantic seaboard ((The process of koinéization also explains the lower degree of geographical variation in Australia, New Zealand, and even Spanish-speaking Latin-American countries, compared to European countries (Trudgill, 2004).)) (Mufwene, 2001; Trudgill, 2004). Early commentators quickly picked up on this “New World” specificity. In the wake of the American Revolution, an English traveler noted the following about the linguistic situation in the young US:

In England, almost every county is distinguished by a peculiar dialect; even different habits, and different modes of thinking, evidently discriminate inhabitants, whose local situation is not far remote: but in Maryland, and throughout adjacent provinces, it is worthy of observation, that a striking similarity of speech universally prevails; and it is strictly true, that the pronunciation of the generality of the people has an accuracy and elegance, that cannot fail of gratifying the most judicious ear.The colonists are composed of adventurers, not only from every district of Great Britain and Ireland, but from almost every other European government, where the principles of liberty and commerce have operated with spirit and efficacy. Is it not, therefore, reasonable to suppose, that the English language must be greatly corrupted by such a strange intermixture of various nations? The reverse is, however, true. The language of the immediate descendants of such a promiscuous ancestry is perfectly uniform, and unadulterated; nor has it borrowed any provincial, or national accent, from its British or foreign parentage. (Eddis, 1792, 59-60)

The contrast between the mosaic of Britain and the monolith of Northern America from a linguistic perspective is stark. What Eddis describes – the arrival of “colonists […] from every district of Great Britain and Ireland”, and the subsequent fusion and “intermixture” of their different speech patterns into a large linguistic melting pot – perfectly corresponds to the process of koinéization. What is also striking is the paradoxical description of North American English as somehow both an alloy and “unadulterated” in purity. In particular, Eddis attributes this purity to a) the homogeneity of Northern American linguistic patterns, and b) the fact that these are regarded as stripped from regional (“provincial”) peculiarities, and thus, closer to a standard.

Likewise, less than forty years later, James Fennimore Cooper would describe the uniformity of Northern American English – something he attributes to the alleged high moral character of Americans, and to their conquering spirit:

If the people of this country were like the people of any other country on earth, we should be speaking at this moment a great variety of nearly unintelligible patois […]. When one reflects on the immense surface of country that we occupy, the general accuracy, in pronunciation and in the use of words, is quite astonishing. This resemblance in speech can only be ascribed to the great diffusion of intelligence, and to the inexhaustible activity of the population, which, in a manner, destroys space. (Cooper, 1828, 125-126)

2.3. Regional patterns

In spite of these descriptions, some forms of regional variation developed, largely due to different forms of koinéization. The process of koinéization is contingent on the particular “blends” of settlers that are present. More specifically, the different proportions of variants – in the form of different pools of colonists – led to different configurations of features, and account for regional variation in the eastern US. In particular, North American colonies saw the arrival of the following settlers in its early stages (Mufwene, 2001; Schneider, 2003a):

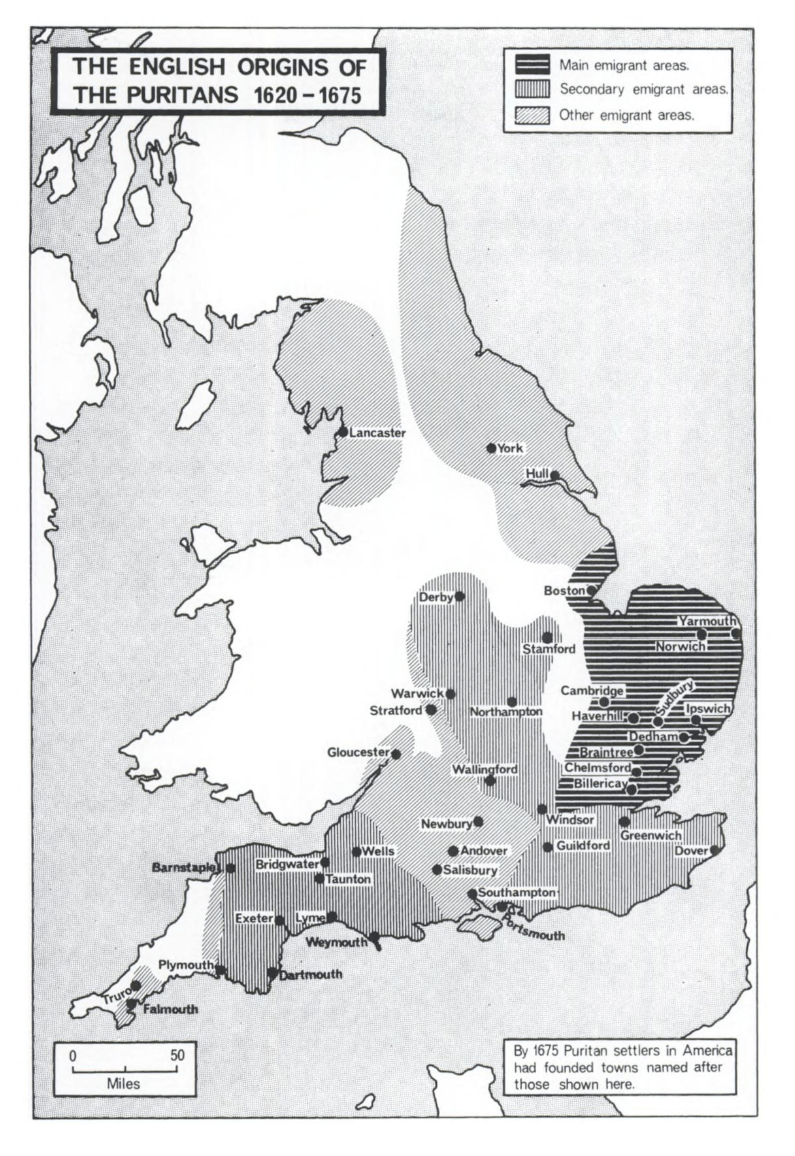

- New England colonies: overwhelming majority of puritan farmers from East Anglia, as well as from the southwest of England.

- Middle colonies: colonists from southern England, northern England, and Scotland.

- Southern colonies: landed aristocracy from southern England, colonists from northern England, Scotland, Ulster, and a significant enslaved population from West Africa and the Caribbean.

These settlement patterns describe a north-south continuum, ranging from most to least homogeneous pools of settlers. New England emerges as strikingly monolithic socially. In particular, New England colonists mostly migrated in family units and “continued to interact among themselves in much the same way as they had in the metropole” (Mufwene, 2001, 159). Although farmers relied on indentured servants from other parts of England, they mostly spoke with each other. Such a social organization produced lower levels of dialect contact (hence less intense forms of koinéization), so that the speech in New England remained much closer to speech in the home colony (Mufwene, 2001). Figure 2.6 shows the geographical origin of puritan colonists in the early stages of settlement. The colonists overwhelmingly came from non-rhotic regions of England – London and its surroundings, and East Anglia. As such, non-rhotic speakers outnumbered rhotic ones. This pool of early settlers explains why lack of rhoticity gained a foothold in New England, rode out the process of koinéization, and is still a predominant feature in contemporary New England dialects (Labov et al., 2006).

Conversely, the South was the stage for much more complex forms of dialect contact. The koiné that developed in the Southern states is a testament to the complex settlement history of this part of the continent, and preserves many elements from different regional dialects. Traditional Southern linguistic features (until roughly the mid-20th century) included the following features (Schneider, 2003b):

- the FOOT-STRUT split (from southern English dialects);

- plural verb –s (for instance they sees) (from northern English dialects);

- double modals (ex: he might could) (from Ulster Scots dialects);

- specific lexicon (ex: biddable for “docile”, barefooted for “undiluted”, etc.) (from Ulster Scots dialects);

- specific lexicon (ex: jazz, jive, voodoo, banjo, hip, etc.) (from West African and African American dialects);

- partial loss of rhoticity (from southeastern English dialects).

The last point is of particular importance as loss of rhoticity was brought by the landed aristocracy that came from the southeast of England. This means that the pronunciation of /r/ also had a specific social form of variation: loss of rhoticity was exhibited by higher social strata (large plantation owners, etc.), and rhoticity by intermediate or lower social strata. In such configurations, koinéization often led to a form of reallocation, rather than leveling: competing linguistic variants are converted to illustrate a new opposition (see Britain, 2012; Dodsworth, 2017; Trudgill, 2004). In the South, rhoticity (or lack thereof) was interpreted by the population as indicating a particular social class. Loss of rhoticity thus became a prestige feature, due to being associated to high status speakers (Baranowski, 2007).

3. The West and General American

3.1. Westerning

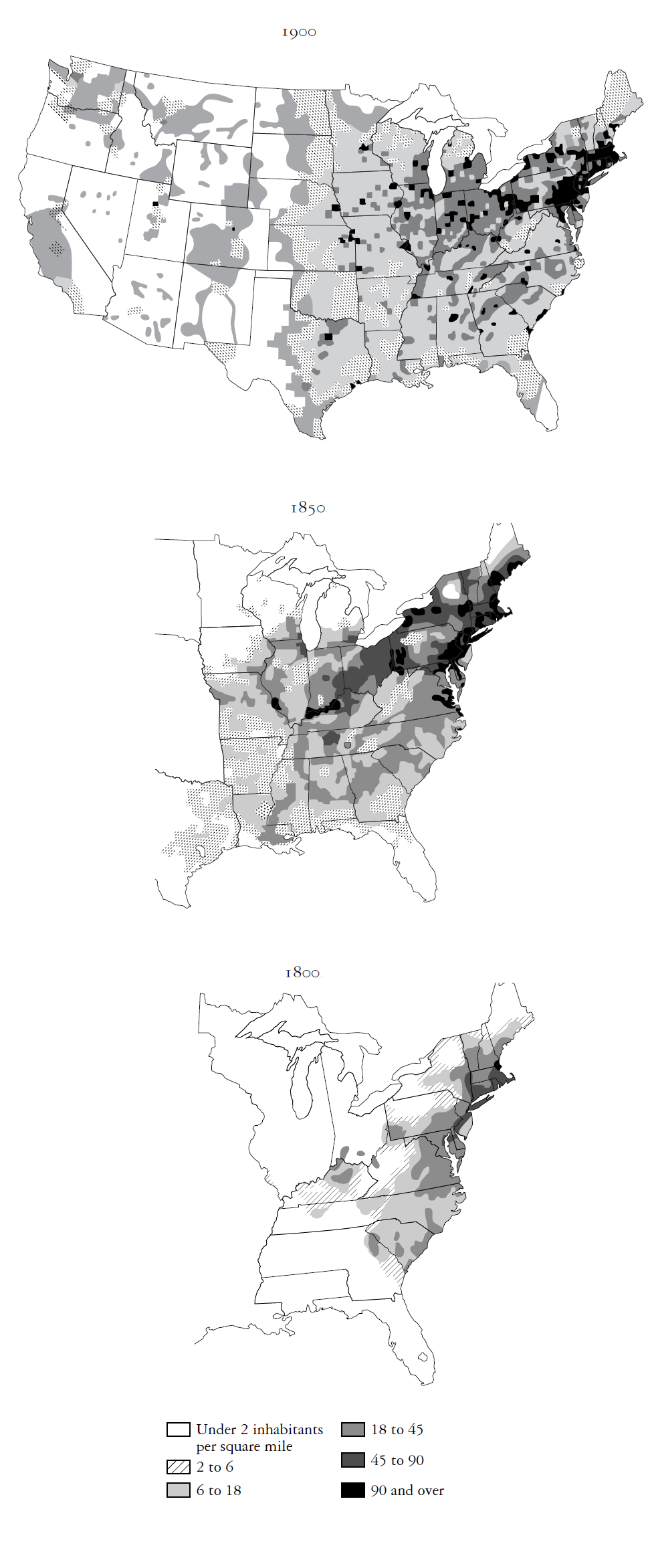

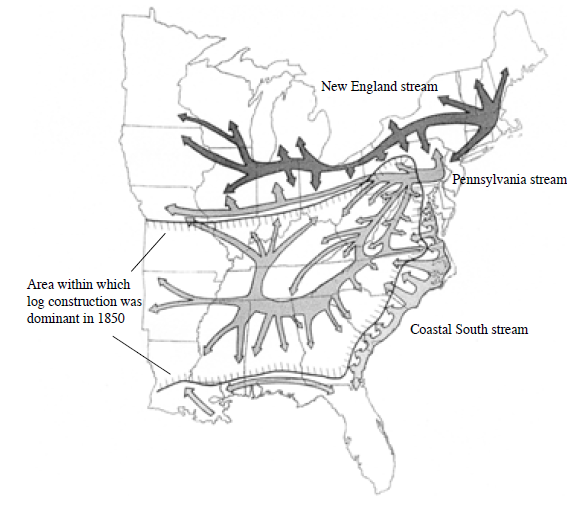

Dialect contact and dialect mixture continued to occur in North America well after the establishment and development of colonies on the coast. Settlers spread from the densely populated east and slowly pushed their way in the North American mainland. This development led to the establishment of inland settlements, and was achieved through the routine exclusion and forced dispossession of the Native American population (Norton et al., 2008). In particular, the 19th century saw the exponential acceleration of westward expansion (figure 2.7). At the beginning of the 1800s, most of the population was clustered around the eastern coast, where colonies initially developed and prospered. A hundred years later, approximately half of the North American continent was firmly settled, in addition to the south of the Pacific coast.

The area west of the Mississippi river – often referred to as the Midwest – was the stage for considerable dialect contact and dialect mixture in the 19th century, as settlers from diverse parts of the Atlantic coast went west to build new settlements. Namely, the Midwest saw the arrival of speakers from the North (formerly Northern colonies/New England), the Midlands (formerly Middle colonies) and the South (formerly Southern colonies) (figure 2.8). This led to processes of koinéization, as these groups of speakers a) spoke different albeit mutually intelligible dialects (of English), and b) found themselves in tabula rasa situations, as there was no prior existing population speaking the language in question. In particular, the process of koinéization manifested itself in the Midwest in the following phenomena:

- leveling – i.e., the reduction in the number of variants (semantically equivalent forms).

For instance, speakers in the upper Midwest initially had two variants to refer to a frying pan, a) spider, from the Northern dialect, and b) skillet, from the Midland dialect. There, the rarer variant (i.e., spoken by a smaller proportion of speakers) spider was gradually leveled out, so that the population eventually only used skillet (Romaine, 2001).

- simplification – i.e., the koiné becomes grammatically more regular, with fewer exceptions.

For instance, preterit irregular forms burnt and dreamt were progressively replaced by burned and dreamed.

- reallocation – i.e., different variants are repurposed by the population to illustrate a new difference.

Dodsworth (2017) provides the example of two variants used to refer to the object used to carry water, a) a pail, from the Northern dialect, and b) a bucket, from the Midland dialect. As a result of reallocation, in the upper Midwest, pail eventually was used to refer to the object when it is made of wood, and bucket when it is made of metal. In other words, both variants, have survived, but only because the population understand them as no longer being semantically equivalent. Likewise, Romaine (2001) gives the example of the verbs creep and crawl – respectively from the Northern and Midland dialects – which underwent reallocation: creep was eventually used to describe infants when they move on their belly, and crawl when they move on all fours.

Additionally, these processes were reiterated with each new settlement on the Frontier, producing remarkable levels of linguistic homogeneity in the Midwest. In fact, the 19th century corresponds to an almost continuous process of koinéization, occurring parallel to westward expansion, as each new settlement represented an opportunity for dialect mixture to occur. As the Frontier progressed further west, new settlements emerged, leading to renewed interaction between different settlers, and producing even more homogeneous speech (Labov et al., 2006; Mufwene, 2001). This phenomenon – the direct consequence of the westward settlement pattern of North America – is known as westerning, understood as the fact that “the further west one goes, the more dialect mixture one encounters” (Davis and Houck, 1996, 60). Language variation in North America consists of an east-west linguistic continuum: geographical variation is at its peak in the east, and gradually dwindle as one goes further west. This is still the case in contemporary North American English, with dialect areas being more sharply defined in the eastern half of North America (Labov et al., 2006).

3.2. Contemporary North American sound changes

That is not to say that North American English is solely determined by its past. In addition to the lengthy process of dialect mixture, English in North America also underwent a significant number of major language changes, resulting in even greater differences between English varieties on both sides of the Atlantic. The following changes became widespread in the 20th century, and are now part of the national standard:

The COT-CAUGHT merger ((This phenomenon is also referred to as the THOUGHT-LOT merger or the low-back merger in the literature.)): words in <auC> ((“C” stands for “consonant”.)) (daughter, caught), <aw> (saw, law, raw), and some words in <ough> (thought, sought, bought) rhyme with lot. In dialects that haven’t undergone the change (such as the British standard, RP), these words are still pronounced with a distinct vowel (/ɔ:/) and rhyme with door.

The feature is an ongoing sound change that has spread to most regions of the US (Labov et al., 2006). A few regional dialects, particularly in the South and in the North, retain a distinction between COT and CAUGHT lexical sets: for most speakers of these varieties, words of these two lexical sets are pronounced with distinct vowels.

Yod-dropping: the [j] sound in the vowel /ju:/ disappears when it is preceded by an alveolar consonant (i.e., /t,d,s,z,n,l/), such as in tune, dune, suit, resume, newt, or lewd. Tune and toon thus become homophones. The feature is an ongoing sound change that is found in most regional varieties of US English (Labov et al., 2006).

T-tapping: intervocalic /t/ is realized with a flap (which is acoustically similar to /d/) when it is preceded by a stressed vowel. Thus, latter and ladder are homophones. The feature is an ongoing sound change that is found in virtually all regional varieties of US English (Labov et al., 2006).

The MERRY-MARY-MARRY merger: the vowels /ɛ/ (ex: very), /æ/ (ex: carry), and historic /eɪ/ (ex: Mary) become [ɛ] before intervocalic /r/. As a result, the words merry, Mary, and marry are perfectly homophonous, and rhyme with cherry. In dialects that have not undergone the merger (for instance in RP), these words are still realized with distinct vowels. The merger is widespread in most of North America, but some regional dialects – in particular on the east coast – preserve the distinction (Labov et al., 2006).

Table 1 sums up the major phonological features of the contemporary British and North American standards. The estimated period when these changes emerged are indicated within parentheses; “ongoing” means the change is recent, and is still subject to high levels of geographical and/or social variation. The table shows that whilst some features of British English have remained in North American English (ex: the FOOT-STRUT split), others have been leveled out (ex: the TRAP-BATH split). Some of these features, such as loss of rhoticity, developed when North America was being settled, and thus spread partially in North America. They were, however, eventually leveled out, but remain in some regional dialects (ex: loss of rhoticity in New England varieties). Moreover, both varieties have since kept undergoing language change, which explains the differences between British and American linguistic patterns.

| British standard (RP) | North American standard (GA) |

|---|---|

| Hw-w merger (10th-14th) | Hw-w merger (ongoing) |

| FOOT-STRUT split (mid-17th) | FOOT-STRUT split |

| Loss of rhoticity (late 17th-18th) | * |

| TRAP-BATH split (18th) | * |

| T-glottalization (ongoing) | * |

| * | COT-CAUGHT merger (ongoing) |

| * | Yod-dropping (ongoing) |

| * | T-tapping (ongoing) |

| * | MERRY-MARY-MARRY merger (ongoing) |

The table shows changes that occurred in the national standard. In addition to these, some sound changes developed in specific regions of the US and Canada, further heightening geographical variation in North America (see Glain, 2015; Labov et al., 2006).

Conclusion

The development of English in North America is contingent on the way this part of the world was colonized, settled, and peopled. Early on, North American colonies saw the exclusion of indigenous and enslaved population, which limited their influence to purely lexical elements. The colonization style, the power balance at hand, and the social structures that developed in these European settlements, conditioned the way linguistic accommodation took place: marginal and socially subordinate groups of speakers were expected or required to speak the dominant language – i.e., the language spoken by the group in power. This linguistic convergence was largely unreciprocated by English (and more broadly European) speakers. The linguistic dominance of English – a direct consequence of English political and territorial hegemony – almost means that other European speakers were expected to adapt to local speech. North American English consists of a noteworthy number of lexical substrates (African, Native American, Dutch, French, etc.), but with very little grammatical or phonological influence from these languages.

The “New World” was, however, the focal point for dialect contact and koinéization. The four centuries of European settlement of this part of the continent coincide with routine processes of a dialect mixture that occurred parallel to the westward push of the Frontier. This koinéization produced a unique configuration of British dialectal features: although each of these features could be heard in the British Isles, their combination with different regional features is what distinguished North America early on. Koinéization also led to the emergence of much more uniform linguistic features in North American colonies. Moreover, North America saw the emergence of endemic sound change – such as the COT-CAUGHT merger. All of these factors – dialect contact, the reconfiguration of linguistic features, the development of North American sound changes, and, to a lesser degree, contact with other languages – account for the specificities of North American English. Hopefully, this article dispelled some long-lasting myths around North American English – that it is either “closer to old English”, or, conversely, more modern than English spoken in the British Isles.

Notes

Bibliography

BADIA BARRERA, Berta. 2015. A sociolinguistic study of T-glottalling in young RP: Accent, class and education. PhD Dissertation, under the supervision of Peter Patrick and David Britain, University of Essex.

BARANOWSKI, Maciej. 2007. Phonological Variation and Change in the Dialect of Charleston, South Carolina. Durham: Duke University Press for the American Dialect Society.

BLAXTER, Tam and COATES, Richard. 2020. “The Trap–Bath Split in Bristol English”, English Language & Linguistics, volume 24, n°2, pp.269-306. URL: https://doi.org/10.1017/S136067431900008X.

BOYER, Paul S, CLIFFORD, E. Clark Jr., HALTTUNEN, Klaren, FETT, Joseph F., SALISBURU, Neil, SITKOFF, Harvard and WOLOCH, Nancy. 2011 (2008). Enduring Vision. A History of the American People. Boston: Wadsworth Publishing.

BRITAIN, David. 2012. “Koineization and Cake Baking: Reflections on Methods in Dialect Contact Research”, in Bernhard Wälchli et al. (eds.), Methods in Contemporary Linguistics. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton, pp.219-38.

CALLOWAY, Colin G. 2013 (1997). New Worlds for All: Indians, Europeans, and the Remaking of Early America. Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press.

COOPER, James Fenimore. 1828. Notions of the Americans. Picked up by a Travelling Bachelor. New York: Stringer & Townsend.

DAVIS, Lawrence M. and HOUCK, Charles L. 1996. “The Comparability of Linguistic Atlas Records: The Case of LANCS and LAGS”, in Edgar W. Schneider (ed.), Focus on the USA. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company, pp.51-62.

DODSWORTH, Robin. 2017. “Migration and Dialect Contact”, Annual Review of Linguistics, volume 3, pp.331-46. URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.1146/annurev-linguistics-011516-034108.

EDDIS, William. 1792. Letters from America, Historical and Descriptive; Comprising Occurences from 1769 to 1777. London: C. Dilly.

GILBERT, Martin. 2013 (1968). The Routledge Atlas of American History. London: Routledge.

GILES, Howard and SMITH, Philip M. 1979. “Accommodation Theory: Optimal Levels of Convergence”, in Howard Giles and Robert N. St Clair (eds.), Language and Social Psychology. Oxford: Blackwell, pp.45-65.

GLAIN, Olivier. 2015. « Variations et innovations phonétiques en anglais américain », La Clé des Langues. URL: https://cle.ens-lyon.fr/anglais/langue/phono-phonetique/variations-et-innovations-phonetiques-en-anglais-americain.

HACKER, J. David. 2020. “From ‘20. and Odd’ to 10 Million: The Growth of the Slave Population in the United States”, Slavery & Abolition, volume 41, n°4, pp.840-55. URL: https://doi.org/doi: 10.1080/0144039x.2020.1755502.

HICKEY, Raymond. 2020. “Re-Examining Codification.” Language Policy, volume 19, n°2, pp.215-34, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10993-019-09523-2.

LABOV, William, ASH, Sharon and BOBERG, Charles. 2006. The Atlas of North American English: Phonetics, Phonology, and Sound Change: A Multimedia Reference Tool. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

MUFWENE, Salikoko S. 2001. The Ecology of Language Evolution. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

NORTON, Mary Beth, SHERIFF, Carol, KATZMAN, David M., BLIGHT, David W., CHUDACOFF, Howard P., LOVEGALL, Fredrik and BAILEY, Beth. 2008. A People and a Nation. A History of the United States. New York: Houghton Mifflin.

PAULLIN, Charles Oscar. 2013 (1932). Atlas of the Historical Geography of the United States, ed. John K. Wright. Washington, D.C.: Carnegie Institution. Digital edition edited by Robert K. Nelson et al.

ROMAINE, Suzanne. 2001. “Contact with Other Languages”, in John Algeo (ed.), The Cambridge History of the English Language, Volume 6: English in North America. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp.154-83.

SCHNEIDER, Edgar W. 2003a. “The Dynamics of New Englishes: From Identity Construction to Dialect Birth”, Language, volume 79, n°2, pp.233.81. URL: https://dx.doi.org/10.1353/lan.2003.0136.

---. 2003b. “Shakespeare in the Coves and Hollows? Toward a History of Southern English”, in Stephen J. Nagle and Sara L. Sanders (eds.), English in the Southern United States. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp.17-35.

TRUDGILL, Peter. 2004. New-Dialect Formation: The Inevitability of Colonial Englishes. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2004.

---. 1986. Dialects in Contact. Oxford: Blackwell.

WELLS, John C. 1982. Accents of English: An Introduction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Pour citer cette ressource :

Marc-Philippe Brunet, Colonization and koinéization: On the emergence of North American English, La Clé des Langues [en ligne], Lyon, ENS de LYON/DGESCO (ISSN 2107-7029), mars 2025. Consulté le 12/02/2026. URL: https://cle.ens-lyon.fr/anglais/langue/langlais-americain/colonization-and-koineization-on-the-emergence-of-north-american-english

Activer le mode zen

Activer le mode zen