The Scottish Education System and Scotland’s Languages Policy

In this presentation, I will go over some of the facets of the Scottish education system, and I will also talk about my specialty, which is modern languages. I was a modern languages teacher for twenty-five years: I taught German and a little bit of French. I then began working for Education Scotland, which is the National Agency for Education – we are a branch of the Scottish Government.

1. An Overview of the Scottish Education System

The UK has a population of 65 million; Scotland has a population of just under 5.5 million. Out of the principalities (Scotland, Northern Ireland and Wales), we have the largest population. Northern Ireland is just over a million, and Wales is about 3.5 million. England obviously has most of the population, which is why people often consider England the United Kingdom.

We have just over 4 000 primary schools, which range completely in size. Some of these schools are particularly small, especially in rural areas such as the Highlands area. There might be only one teacher and three pupils. However, some of the schools in Glasgow and Edinburgh can be huge and have up to 400 or 500 pupils. We also have one primary school that has 900 pupils.

In our secondary system, we have 359 secondary schools. Again, those range in size, and we have in the Scottish Highlands what we call “through schools”, which is primary and secondary together. In the Highlands and the rural areas, children may have to stay in a sort of Youth Hostel next to the school, because they live so far away.

We also have 133 special schools in Scotland, which are dotted over the country. But it can be difficult for families with children with special needs, because the schools can be very far away from where they live. And that involves long journeys, because these children would not want to stay overnight.

|

|

What our standing mission is for Education Scotland is bringing together national support and challenge. My job comes under “national support”, and “challenge” comes from the Inspectors. When the inspectors come into a school, they are not inspectors of a subject any more, they are inspectors of pedagogy, of planning, of looking outwards and seeing how the school can self-evaluate and insure improvement. If, when they go to one of those schools, they see that there is a particular difficulty in, for example, languages, the inspector will contact me and I will go and work with that school to see how we can support languages a bit further. The same would happen in Mathematics or in English, or in Art and Design, etc.

One of the defining missions of our Scottish Government is to secure continuous improvement and opportunities for all learners. The Scottish Nationalist Party’s and our First Minister’s mission is to eradicate inequality through education. Nicola Sturgeon has said she will be judged on how well she has provided an education system that can eradicate inequality. As you can see, the SNP is very socialist-leaning.

Structure-wise, between the ages of 0 to 2, you can choose to send your child to a private nursery, costing you a lot of money, or you can employ a nanny or a child-minder. Up until very recently, a lot of our employment policies were not family-friendly at all, and we ended up with people dropping their children off and then rushing to work. We are trying to move policy on so that we can actually support people, especially women, to get back to work. Opening up nurseries a lot earlier in the morning would for instance enable people to drop their children off before going to work.

From the age of 3 onwards, there are currently 600 hours of nursery education provided for free by the state. You don’t have to send your child, but our uptake is about 97%. Most parents want their child to experience preschool or “early years”, as we call it. For the families that are in some level of difficulty, social workers or preschool teachers have determined that it would be good for the children to go to nursery school a bit earlier, from the age of 2. However, this is about to change: the SNP has drawn a national policy which will give Scotland 1 140 hours of preschool. It will allow every child to have a longer preschool education before they start their formal education, which starts with primary school roundabout the age of 4½ or 5. Parents can defer by a year; some of the parents of very young children who are 4 ½ might think that their child is not mature enough and apply to defer for a year. That does not happen very often, but it can happen. Sometimes we have absolutely tiny children in little school uniforms going off to start Primary 1 and their hands are so small they can’t even hold pens. However, the curriculum in that first year is very play-based, and then it moves on to a more formal education.

|

|

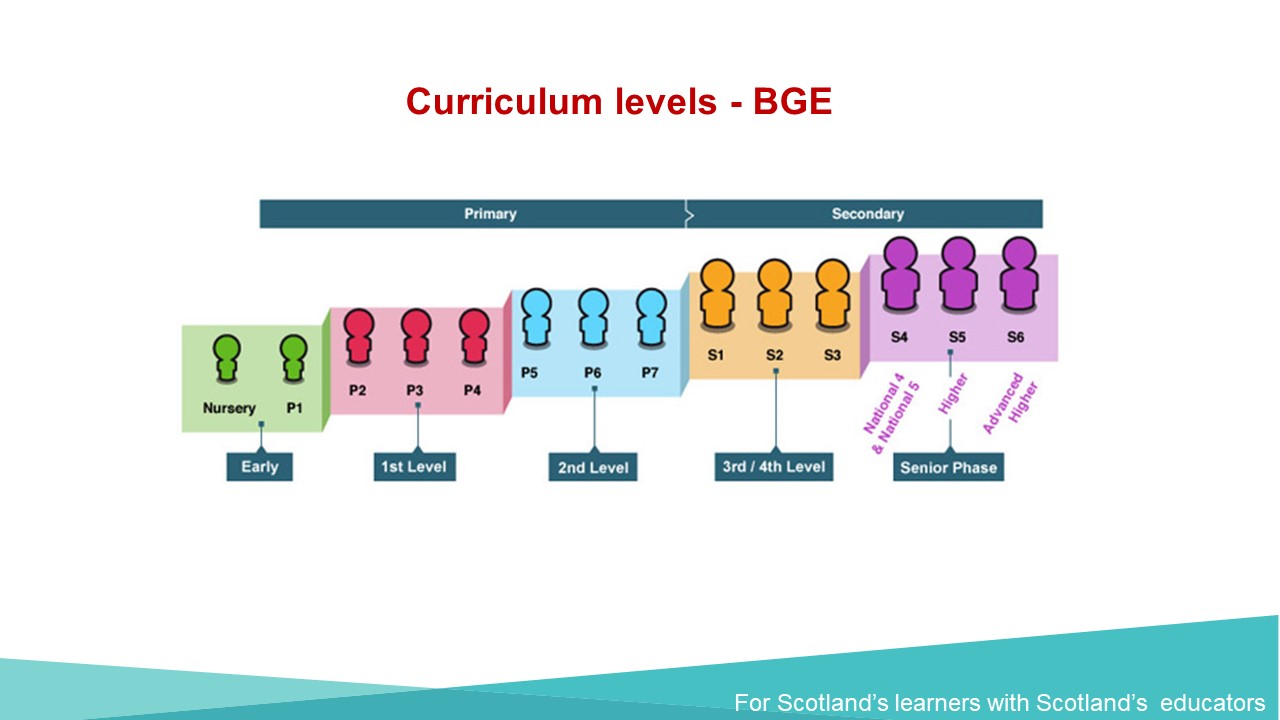

Children have seven years in the primary school. They start Primary 1 at around 5 and finish primary school at roundabout 11½ or 12. They go to secondary school aged 11½ or 12, and secondary school is compulsory until the age of 16, at which point a young person can leave the education system if they have a job or an apprenticeship lined up. Then the nomenclature changes: P1 is for Primary 1, and it goes up to P7. Then we have S for Secondary, which is S1 to S4.

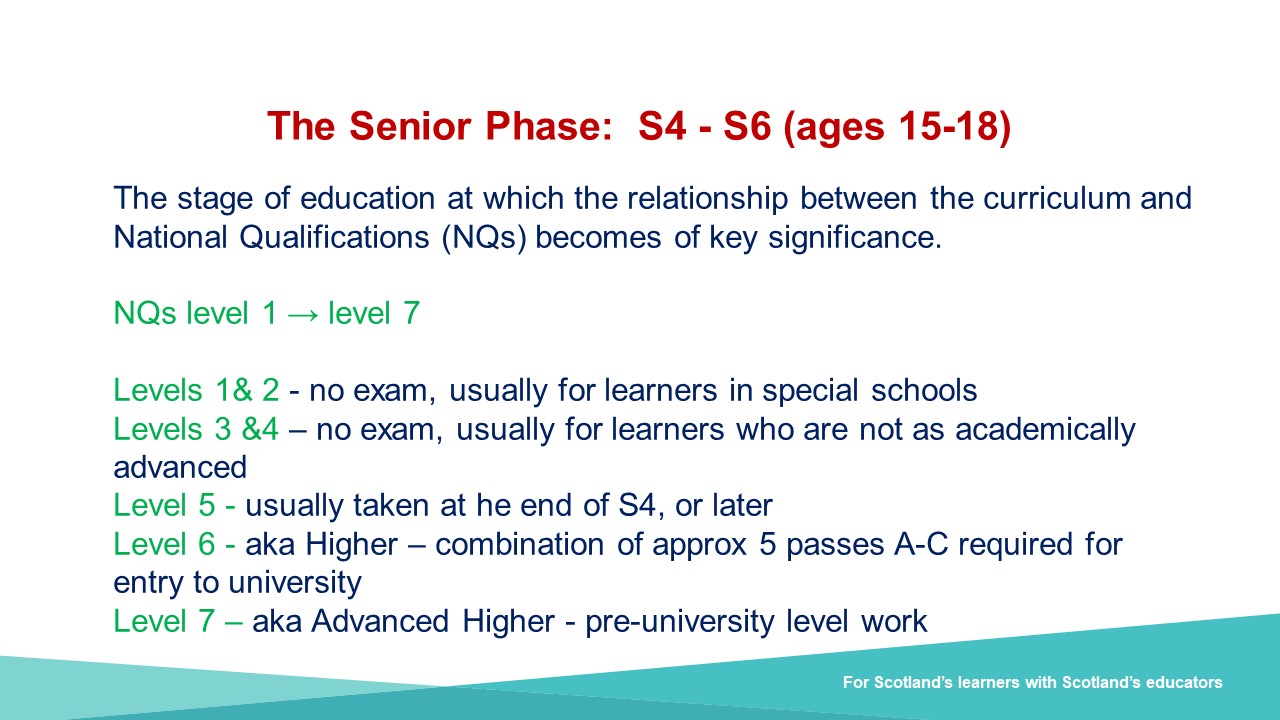

Most young people stay in school after 16. If they finish S4, they move to S5, and then from that they move into S6. If they want to, they can go on to college or they can go into further education. They can’t go to university at the age of 16 because they have not achieved the qualifications required, as a benchmark for university entrance. Therefore, if you leave at 16, you have got fewer pathways. If the pupils stay on for longer, in the 5th year, they have the opportunity to do a group of qualifications called Highers, which are roughly equivalent to the English A-Level. In Scotland, they have to do five to be able to then go on to higher education or university.

That is our system in a very simplistic way: you start at 5, you can finish at 16 but most people stay on until the 5th year and most people stay on again in the 6th year, because it gives them an extra year to take more qualifications and exams.

2. Curriculum for Excellence

Our curriculum is called “Curriculum for Excellence” (CFE). We have thought for a long time about how we could reform our curriculum and we now have had it in place in Scotland for the past ten years. At this point, I should say that Scotland is completely separate from England, Wales and Northern Ireland in terms of the education system, and our exam system is also different. In England, Wales and Northern Ireland, young people will sit A-levels, and in Scotland they will sit Highers. There is a devolved autonomy given to the Scottish Government in terms of education, but also laws for instance. Because children start a year younger than in England, around 4½ or 5, they can go to university at about 16½ or 17, and they will never meet an English equivalent at university of that age. I am not saying that it is a good thing for the Scottish system, but it is different and we are very proud of it.

Our curriculum is called “Curriculum for Excellence” (CFE). We have thought for a long time about how we could reform our curriculum and we now have had it in place in Scotland for the past ten years. At this point, I should say that Scotland is completely separate from England, Wales and Northern Ireland in terms of the education system, and our exam system is also different. In England, Wales and Northern Ireland, young people will sit A-levels, and in Scotland they will sit Highers. There is a devolved autonomy given to the Scottish Government in terms of education, but also laws for instance. Because children start a year younger than in England, around 4½ or 5, they can go to university at about 16½ or 17, and they will never meet an English equivalent at university of that age. I am not saying that it is a good thing for the Scottish system, but it is different and we are very proud of it.

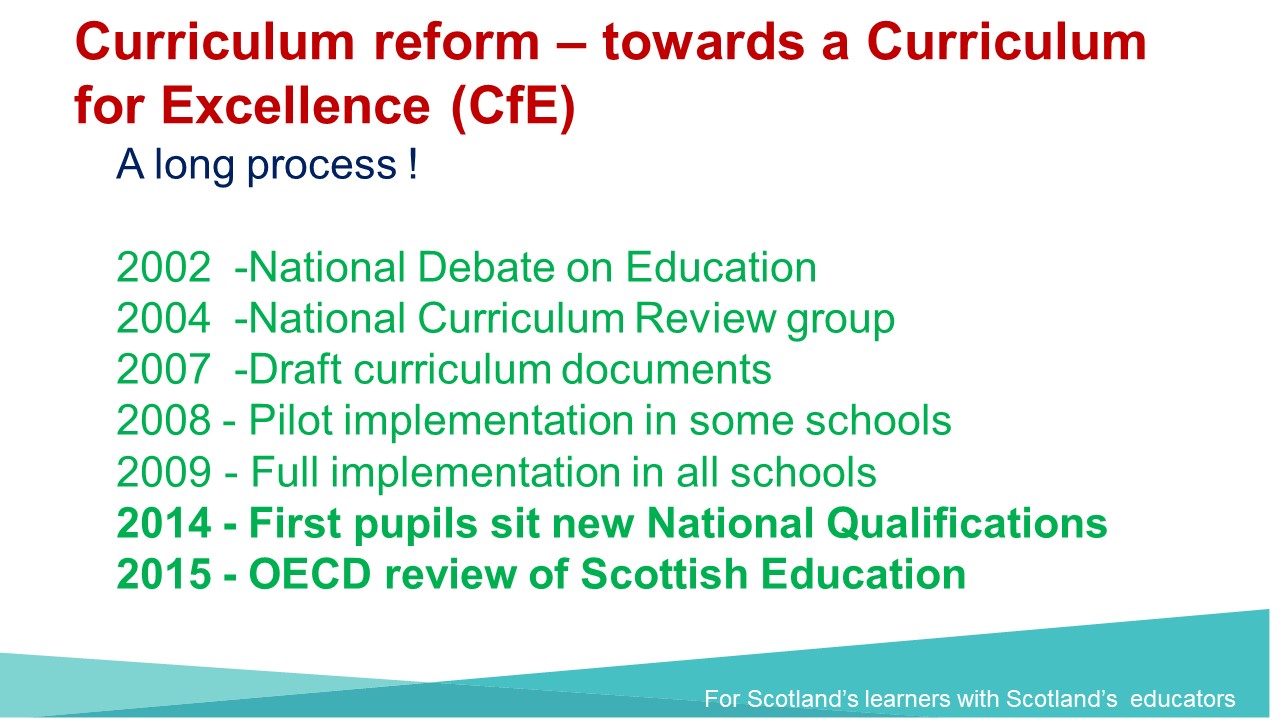

Our curriculum had to be refreshed and reformed. When I was teaching, before Curriculum for Excellence came about, it was almost the same central tenets of the curriculum that I had experienced as a pupil. And yet, society had moved on, hugely. By the time I became a teacher, it was very odd to think that the curriculum was still as rigid as it had been when I was a pupil. A lot of work and research went into this reform and we looked outwards, beyond Scotland, we looked towards Canada, Finland, and other different education systems where we could see they had managed to bring about equality as well as keeping standards high in terms of education. We had a very long process, and I was still a teacher when we had the National Debate on Education in 2002. We are quite a small country and we have enough in way of connectivity to be able to talk to just about every single teacher: the Government and Education Scotland can get in touch with them. We started debates, which at local level were held in the schools at the end of the day, to talk about the new curriculum so that we could feed in as teachers to the Government, to Education Scotland, and say “we think this will work” or “we don’t like this”. The debate took a long time, and not everybody joined in, but quite a large majority of teachers voiced their opinions. We had a first draft of the new curriculum in 2007, then we started piloting in 2008. I remember doing that in one class in my school and looking at how my subject, the modern languages, was about to change.

From 2009 onwards, we implemented this new curriculum, Curriculum for Excellence. The exams also had to change to reflect the changes that had been made to the curriculum: the pupils sat the new qualifications in 2014. In 2015, we got the OECD visit and they reviewed Scottish education: it was a nerve-racking time because it had only been six years since we had implemented the curriculum, so we still had pupils in schools that had not gone through the whole of primary school or secondary school under that new curriculum.

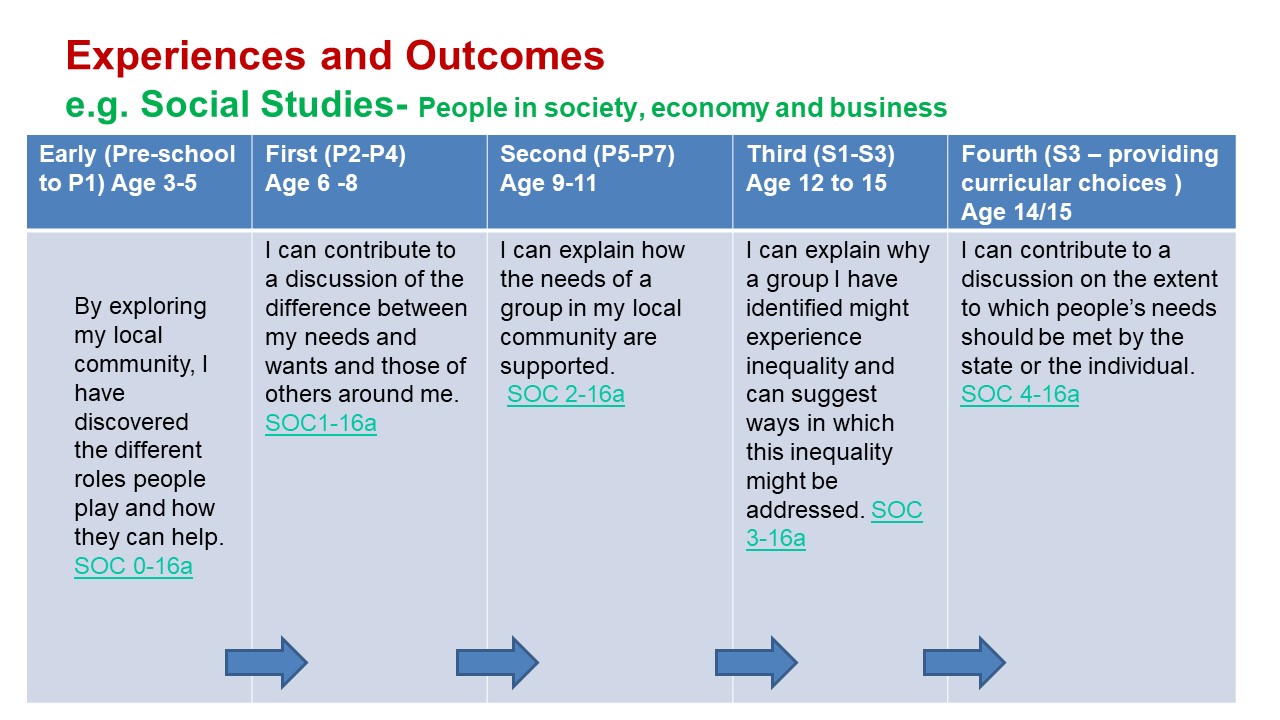

We made the curriculum much more flexible than the previous one, and there was much more autonomy given to schools and to teachers about what they were going to teach within a certain parameter, which is what we call the “experiences” and “outcomes”. But how you want to go about it and how you want to teach these was given to the teachers to decide. It also opened up the contextualisation of learning. For some of our pupils, for instance those in the Highlands, it is very interesting to do a lot of outdoor learning, to be working at a beach on the making of a boat: that way they are covering the experiences and the outcomes of technologies. Depending on the areas, you can look at the history of coal mining and at what happened politically when the coal mines were closed and the impact it had on their areas. We realised that before, we were teaching without looking at anybody’s context and we were giving a general curriculum. As I child in Edinburgh, I was learning for example about what was happening in Essex, in the South of England. And I didn’t care – but I would have cared about the mountains and the Glens and the Lochs and the industries in my own country. It is a very light-touch example, but the new curriculum was about looking at the context for learning and it gave a great push to outdoor learning. In primary schools, we now see a lot more children being outdoors, exploring outdoors, having a look at plants and trees, to really enhance their experience of learning.

Not every teacher in Scotland welcomed the new curriculum with open arms though. A number of teachers were very concerned and very worried about seeing the shifting sands in a curriculum that they had been used to, that they had planned and prepared for. There are some teachers who still want to be told what to teach; but the majority of teachers, I would say, prefer to have this autonomy within parameters.

2.1 The Four Tenets of the Curriculum

These parameters are called “experiences” and “outcomes” and are applied to every subject. There are four central tenets of our curriculum:

- We want our children to be successful learners, meaning that we want them be successful in the classroom but also to learn how to learn. Can they apply their knowledge in a different context? Are they good at learning? Have we taught them how to be learners?

- We also want them to be confident individuals, and we give them more opportunity now in the curriculum to develop their confidence. For instance, we encourage children as young as 5 or 6 to talk to the rest of the class, and by doing a presentation and leading a discussion group when they are a bit older. We didn’t have that when I was young, and I remember being really nervous and shocked when I was asked to take an oral language class at university. To have to stand there and do a presentation was an anathema. At the age of 18, I had not done anything like this in my whole career. There are obviously other ways of building confidence, but we try to have our children know what they are learning, why they are learning it and how to improve. Confidence comes through having those tools.

- We also want our children to become responsible citizens of the 21st century, who know what it is like in their context, but who also know to look outwards, globally, at the world and think: “we need to be responsible”.

- We want our children to grow up to be effective contributors to society who can actually make a difference in the world.

This is very high level, but all those four tenets are achievable, to different degrees, depending on the children and their context. These four tenets come from the heart, if you like. We want to make sure that we are producing young people who are fit and ready for the world, whether that be the world of work, the world of academia, etc.

2.2 Broad General Education (BGE)

|

|

We have two stages in school education […]: we have what we call the broad general education (BGE), from 3 to 15, and then we have the senior phase, which is from S4 to S6. Pupils can choose to leave after S4, if they are 16 by then. Children are exposed to a wide variety of learning opportunities, of contexts for learning. We try to keep it as broad as possible because that has always been a tradition in Scotland that we would have children that could read and write as well as they could do maths and speak a foreign language. We want to have well-rounded citizens in that regard. The broad general education means to develop the knowledge, skills, attributes and capabilities of the four capacities of Curriculum for Excellence.

In this part of the curriculum, we are looking for breadth, as well as depth of learning – we don’t want superficiality in those learnings. That is why this curriculum has been in place for a long time, twelve years in fact. We also need the curriculum to be flexible and adaptable. We are looking, always, with an eye to the future: these are skills that children and young people will need in the future, and that is why we have a particular focus on digital learning, science, technology, engineering, mathematics… We are making sure that we are equipping our young people with enough skills and knowledge that they can take on the world as adults.

During the BGE, the pupils should achieve the highest possible levels of literacy, numeracy and cognitive skills. They will also develop skills for learning, skills for life and skills for work: we are making sure that we have career-ready young people who know what it is like to go into a work environment. We also need to prepare children to understand where they are coming from and what Scotland’s position is. Do they know what Scotland has contributed to the world? Do they know where they stand, where they are economically and historically?

Until Curriculum for Excellence came up, we didn’t have a compulsory section on Scottish History. If you studied History, you could study English History, WWI, WWII, European History, World History, but there was no place for Scottish History. We were not looking at where we had come from to be where we are now. We are now making sure we are opening up channels for young people to understand Scotland’s place in the world, where they are and how they can improve themselves and contribute further to society.

We also want young people to experience challenge and success so that they can develop well-informed views. We call this area “Raising the bar”: young people need to learn to challenge themselves to do better.

|

|

The first section is our BGE. The second section is called the Senior Phase (S4 to S6), where children have decided to stay on at school after 16.

Teaching in Gaelic in Scotland

Gaelic is widely spoken in the Western Isles and part of the Highlands, so we have Gaelic medium education, where every facet of the curriculum is taught in Gaelic (the only subjects not delivered in Gaelic would obviously be English and foreign languages). We also have Gaelic medium schools in the Lowlands of Scotland, because many parents are really interested in having their child brought up bilingual. There are two Gaelic schools in Glasgow and there is a large primary Gaelic medium school in Edinburgh. I believe there are plans to build another one in Sterling. The Gaelic Language Act protects the Gaelic language because we nearly lost it: now, any parent who wants their child to have a Gaelic medium education has the right to do so. What is interesting is that when you look at national exam results, the children at the Gaelic medium schools always do very well in their exams because they operate in two languages. The majority of these children actually do not come from families where Gaelic is spoken at home.

2.3 Curriculum Areas

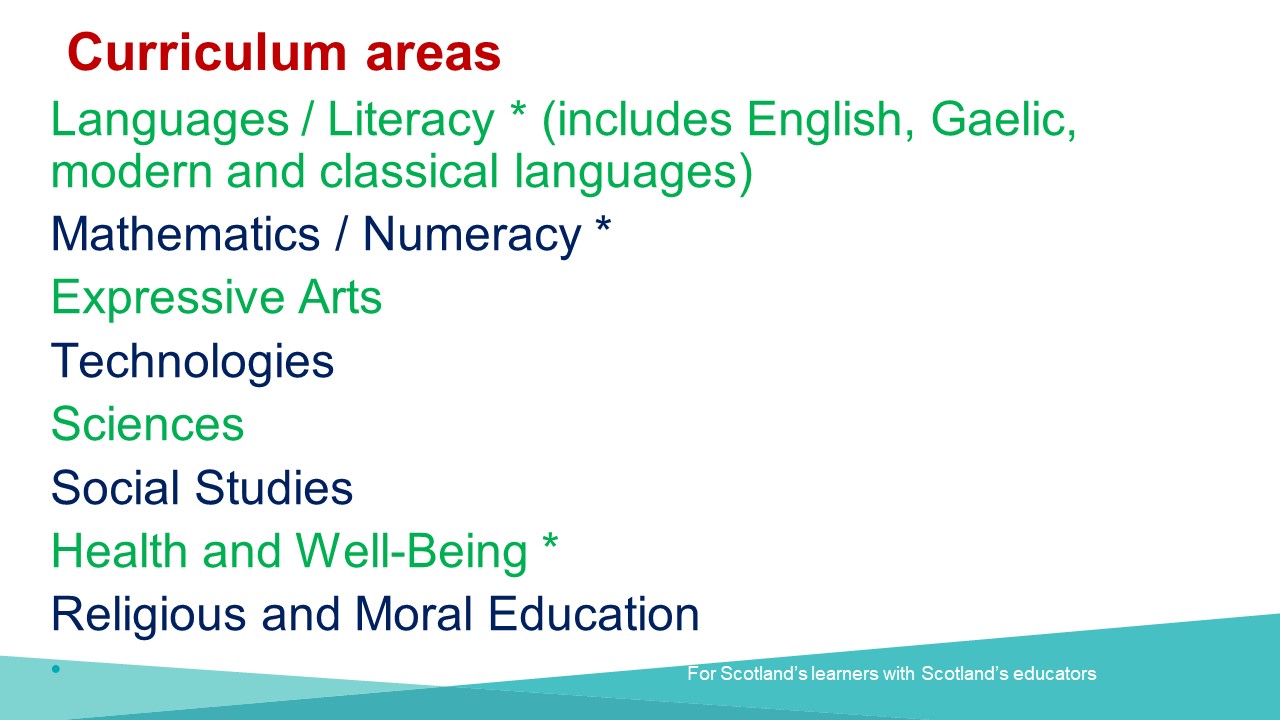

The areas of Languages and Literacy, Mathematics/Numeracy and Health and Well-Being are what we call “the concern of all”. That means that if you are a teacher of Mathematics in a secondary school and the children’s English is poor, it is your responsibility as a teacher of Mathematics to make sure that their English is corrected and upgraded. It is not just the English teacher’s job. But equally, in other subjects such as Geography, when they are looking at more numerical topics, they need to make sure they are using the correct way of working out a problem, so that you are supporting what is taught in Numeracy.

Health and Well-Being has to do with nutrition, exercise, etc. For example, in Modern Languages, pupils would typically learn about food and drink. To add to that, since it is the responsibility of all, you would also be talking about food and drink in terms of health.

We also still have Latin in our curriculum as well: it is taught in very few of our schools, but it is still there (possibly more in the private sector).

For every one of those eight areas, there would be a Senior Education Officer with responsibility for a particular area. We now have a Senior Education Officer for English and another for Literacy. Additionally, there is a Senior Education Officer for Gaelic.

State schools and Private schools

There are two types of schools in Scotland: state schools and private schools. Our private schools are very different from French private schools: they are very expensive and they don’t always follow Scottish curriculum because they might see the English curriculum as being better. The difference between those two types of schools is very much class-based. There are quite a number of private schools in Scotland, particularly in Edinburgh because it is an international city and a city of financers. Within our state system, we have primary schools and secondary schools. We also have learning centres for children before they come to school. There are no other differentiations between types of schools, contrary to England where they have grammar schools, comprehensive schools, Church of England schools, etc. The one difference we would have in the state schools is that we have quite a number of Catholic schools, especially in the West Coast of Scotland, near the Glasgow area, because of the connections with Ireland. They follow the exact same curriculum apart from the Religious and Moral Education.

2.4 Experiences and Outcomes and National Qualifications

|

|

I will now have a look at the parameters, meaning Experiences and Outcomes, in Social Sciences […]. Pieces of learning and advice are called “Experiences” and they are taught in sequential form. The same piece of learning becomes more sophisticated with each level.

After the BGE, at the age of 15, pupils start to reduce the amount of subjects they are taking because they know what it is they want to specialise in. They will be able to choose what they want to focus on in 4th year, 5th year and 6th year. The subjects will be reduced to six or eight, depending on the school and how many national exams they are taking.

At the end of their 4th year, every young person does the exact same national qualifications on the exact same day. The exam period runs between the end of April and the beginning of June. Pupils will usually take between 6 and 8 qualifications of that level. They then move into 5th year, where they shrink down further and take 4 or 5 qualifications. The next level is called “Higher”, which is the Scottish equivalent of the A-level. They will take 4 or 5 of those, but they can also take a combination of Highers. Not every child is going to be academically successful to do 5 Highers, so they can do 2 or 3 in one year, and the rest the next year. In 6th year, pupils may take Advanced Highers, which is pre-university work. However, they may leave school at 17 and go directly to university. In that 6th year, they can take 4 or 5 subjects, but there is a lot of flexibility in the choice of their courses. Most students stay on in 5th year and 6th year because of this flexibility.

A key policy of the SNP is to allow our young people to achieve a positive destination. We don’t want any of our young people leaving school without having somewhere to go, as in university, college, a job or an apprenticeship. We very much have a responsibility to give them that positive perspective. We are working with colleges, universities, employers, and apprenticeship providers to make sure we have a positive destination for all of our young people.

3. Scotland’s Languages Policy

3.1 Languages Acts and Policies

The indigenous languages of Scotland are English, Gaelic and Scots. The Gaelic Language Act was passed in Parliament in 2005 to stabilize the number of students taking Gaelic, and to protect the language and allow it to grow. We nearly lost Gaelic, we were down to very few speakers; indigenous speakers of Gaelic were not having enough children who would also be indigenous speakers of Gaelic. We therefore had to open it out and we now have Gaelic medium schools for children who are not native Gaelic speakers, and we also have two different types of Gaelic teachings. We have Gaelic medium, for native speakers who are taught primarily in Gaelic and Gaelic learners, for pupils who learn Gaelic as if it were a foreign language. The Gaelic Language Act was to protect, stabilise and broaden. There are signs of growth indicating that it is working.

The indigenous languages of Scotland are English, Gaelic and Scots. The Gaelic Language Act was passed in Parliament in 2005 to stabilize the number of students taking Gaelic, and to protect the language and allow it to grow. We nearly lost Gaelic, we were down to very few speakers; indigenous speakers of Gaelic were not having enough children who would also be indigenous speakers of Gaelic. We therefore had to open it out and we now have Gaelic medium schools for children who are not native Gaelic speakers, and we also have two different types of Gaelic teachings. We have Gaelic medium, for native speakers who are taught primarily in Gaelic and Gaelic learners, for pupils who learn Gaelic as if it were a foreign language. The Gaelic Language Act was to protect, stabilise and broaden. There are signs of growth indicating that it is working.

We also have the Scots Language Policy (a policy is different than an Act: an Act is strong and robust, whereas a policy means Scots language is merely encouraged). There are two schools of thought on the Scots language: one says it is just accent and dialect, and that it is a kind of slang, and the other says it is rich, diverse and it is a proper language, with its own grammar.

When I was younger, we were not encouraged to speak Scots: the teacher would tell you off and force you to rephrase in “proper English”. Recently, in a court in Aberdeen, the judge asked a defendant if his name was John Smith, and the man replied “Ay” (which means “yes” in Scots). The judge said: “I’ll ask you again: is your name John Smith?”. The man replied “Ay” again. The judge told him “Say it one more time and you will be taken to jail overnight.” He then asked him again what his name was and the man insisted on saying “Ay”, because it was his language. That is an extreme example, but the man was indeed remanded in custody, because the judge saw it as cheek.

It’s very difficult to have the seismic change that is required in society to stop thinking that Scots is poor English and to move on to considering it a rich and diverse language. But there are so many versions of Scots that it doesn’t have one grammar; it does tend to follow the rules of English grammar, but the vocabulary, which comes from the poetry of Robert Burns and the history of Scottish language, makes it very different. It is a language we should not be embarrassed to speak. The SNP have a vested interest in all things Scottish and have decided to celebrate the fact that we have so many diverse versions of Scots language, not just accents and dialects. The Scots language is very different in Aberdeen and in Shetland, in Dumfries and in Glasgow. In terms of policy and in terms of the curriculum, it means that we encourage the use of Scots: we don’t, for example, mark anybody down because they have written something in Scots, and some teachers in primary and secondary schools actually choose teach in Scots.

The British Sign Language Act is pretty new: it encourages us to teach British Sign Language to children, even if they are hearing children. But it is still quite difficult to get people to teach British Sign Language, as there are very few signers.

3.2 A Brief History of Modern Languages in Scottish Schools

I will now give you a brief history of modern languages in Scotland’s schools. We currently have a modern languages crisis, and we are having some difficulties teaching modern languages in the UK. Living in an Anglophone society puts us at a disadvantage because we think the language of the world is English. Many people think they don’t need to learn another language, because everybody speaks English.

I will now give you a brief history of modern languages in Scotland’s schools. We currently have a modern languages crisis, and we are having some difficulties teaching modern languages in the UK. Living in an Anglophone society puts us at a disadvantage because we think the language of the world is English. Many people think they don’t need to learn another language, because everybody speaks English.

In 1977, and this is a statement from the official guidelines, languages were compulsory in S1 and S2, so ages 12 and 13, but only the “cleverest” (that was the word used in the official text) children would continue languages in S3 and S4. Modern languages were therefore very elitist. Because French was the language of the courts and the palaces, it was seen as very elitist.

In 1987 in Scotland, we had a Minister of Education who actually cared about languages and made it compulsory in 4th year. There was still nothing in primary schools, but modern languages were nonetheless made compulsory from age 12 to 16.

In 1989, the same Minister decided to start the teaching of modern languages earlier because academic research showed that the younger you start learning a language, the easier it is and the more normal it becomes. So we started modern languages in P6. However, we did not offer our primary school teachers the requisite training right away; but what the government did do then was to put some funding in to allow teachers to come out of school and have training for 28 days so that they could upskill themselves in French, German or Spanish. That primary school teacher would then deliver teaching for the whole school through P6 and P7. But when that teacher was ill or moved to another school, there would be no more languages teaching. That system was no sustainable, but it was a great project nonetheless.

In 1993, we had another Minister who kept modern languages in primary schools, but stopped them at S2. We went from 6 years of learning modern languages to 4 years, and only children who really liked languages would continue learning them beyond the age of 13. We therefore created a generation who might not have continued learning languages beyond the age of 13.

From 2008 onwards, we have had the Curriculum for Excellence and we have had modern languages from S1 to S3. But in primary schools, languages have been abandoned because they were not seen as high priority. And since there was no money to sustain modern languages, there was no real impetus to keep modern languages in primary schools. Again, we had a generation who might have had only three years of languages.

However, starting in 2013, we brought in the “1 plus 2” language policy, which comes from the Barcelona Agreement: pupils should speak their mother tongue, plus another two languages. The advice is to start learning modern languages at a much earlier age than was the case before. From 2013, and until 2021, 13 million pounds have gone into languages: that money is to be used mostly for training and upskilling our primary staff so that they can deliver the language. We have to make sure that all of our primary staff can deliver at least some of the languages and make the learning of another language normal. They will start with the basics, such as “enlevez vos anoraks”, “asseyez-vous”, etc, and then bring more and more of the language as the children grow older. They are doing what we call “discreet language lessons”. […] We have got until 2021 to get all primary schools in Scotland ready to deliver modern languages from P1 to P7.

|

|

Modern languages have this now highly political profile and have significant funding behind them. There are different training models across the country, because in our primary schools we have teachers who are fluent in French, or who are absolute beginners. The same is true for other languages, such as Spanish, German, etc. So there must be different models of training depending on where they are at with their language skills. We are basically asking primary staff to take on another duty, which is quite a big ask.

We do have a crisis of languages in UK schools, in England, Scotland and Northern Ireland: the number of students taking languages to Highers or beyond are plummeting. It is still seen as an academic, elitist subject. We are hoping that this policy normalises language learning.

|

|

We use the terminology used in the Barcelona Agreement: L1 is the mother tongue (English or Gaelic in Scotland), L2 is the first additional language, taken from P1 (age 5) until the end of 3rd year in secondary school, which means ten years of L2. And then we add another additional language, L3, which starts in P5 (age 9 or 10) and that can be just once a week, so it is not taught at the same level as L2, which makes it more flexible. The L3 can be any language.

French, Spanish, German, Italian, Gaelic, Urdu, Mandarin and Cantonese are the eight languages that can be studied as an L2 in Scotland. The reason we have reduced it to eight is because there are only eight languages recognised at national level and at examinations. Mandarin, Cantonese and Urdu have very small numbers of students, and they tend to be native speakers. We only had 28 students taking higher qualifications in Madarin last year. We have got quite a large Polish population in Scotland, so there are a lot of Polish people who are lobbying to have Polish recognised as a national qualification.

As for the L3, it can be any language depending on what the school can offer […]. Some teachers were able to teach Russian, Polish, Japanese or Dutch. The weirdest one was Swahili. You still have to have the four skills, so you can’t just do playing exercises: you have to do reading, talking, listening and writing exercises.

The unintended consequence of this policy is that our Scottish children are becoming much more aware of multilingualism and the fact that we live in a pretty small world. It is not just about Europe and traditional European languages: the policy has allowed us to look beyond. Most schools stick to the “traditional” languages for the L3 (French, German, Italian, and Spanish), but some schools teach other languages, such as Swahili or Greek.

3.3 In the Classroom

This is a video of a primary teacher in a small school in the south of Scotland, very near the border with England, who is learning French at the same time as she is teaching it. What you hear is a very unrefined French accent.

This is the same class, age 4 and 5. Sometime they do a story, listening and repeating it. This teacher is a very brave person, she had only done French for two years in secondary school. She uses the French she has and learns alongside the pupils: her accent is not perfect, but she is instilling a confidence and a love of languages in the children, who were really enjoying that experience. It has become normal for them to learn in that way. We recorded that video in 2014 and we have gone back subsequently to see that class, and their French is really good, because they have been using it day in and day out. The teachers in the school encouraged the janitor, the dinner ladies, the head teacher of the school, to be able to speak French. When we went back a few years ago, you could have thought they were in an international school because everyone, even the adults - whether they be the janitors or the support staff - were all talking in French, even if it was just a little bit, like “Bonjour, ça va ?”. It became normal. And that school is typical of a number of schools in Scotland. What we also have done in Education Scotland is provide support for the teachers: for instance, we have sound files in eight different languages for teachers to use until they feel confident enough to use those phrases themselves.

Sometimes, when I think in my darkest moments that I am never going to be able to get this policy implemented, I realise it is worth it.

4. Extracts from the conference

- On the Curriculum for Excellence:

https://video.ens-lyon.fr/eduscol-cdl/2019/ANG_2019_lglen_cfe.mp3

- On contextualised learning:

https://video.ens-lyon.fr/eduscol-cdl/2019/ANG_2019_lglen_contextualised_learning.mp3

- On the four central tenets:

https://video.ens-lyon.fr/eduscol-cdl/2019/ANG_2019_lglen_tenets.mp3

- On Gaelic:

https://video.ens-lyon.fr/eduscol-cdl/2019/ANG_2019_lglen_gaelic.mp3

- On public and private schools:

https://video.ens-lyon.fr/eduscol-cdl/2019/ANG_2019_lglen_private_schools.mp3

- On languages policy in Scotland:

https://video.ens-lyon.fr/eduscol-cdl/2019/ANG_2019_lglen_languages_policy.mp3

- On the 1+2 languages policy:

https://video.ens-lyon.fr/eduscol-cdl/2019/ANG_2019_lglen_barcelona_agreement.mp3

Pour citer cette ressource :

Louise Glen, The Scottish Education System and Scotland’s Languages Policy, La Clé des Langues [en ligne], Lyon, ENS de LYON/DGESCO (ISSN 2107-7029), novembre 2019. Consulté le 26/02/2026. URL: https://cle.ens-lyon.fr/anglais/civilisation/domaine-britannique/the-scottish-education-system-and-scotlands-languages-policy

Activer le mode zen

Activer le mode zen