Scottish Civic Nationalism: An Opportunity for Migrants?

Cette ressource est issue d'une présentation donnée dans le cadre de la journée de formation "Libertés publiques et libertés individuelles (LLCER anglais, monde contemporain)" inscrite au Plan Académique de Formation de Lyon (22 janvier 2021).

"Par ailleurs, la question des droits à conférer aux nouveaux arrivants ou, dans le cadre de bouleversements politiques, à certaines populations implantées depuis longtemps (Afrique de l’Est, Hong Kong, Royaume-Uni, etc.) provoque également de nombreux débats, comme celui sur le droit de résidence ou le droit de vote, posant plus largement la question de la citoyenneté et de sa définition. Dans un contexte où de nombreux pays cherchent à impliquer les citoyens dans la vie politique, se pose la question de l’élargissement du suffrage aux jeunes à partir de 16 ans (Écosse) ou aux étrangers pour les élections législatives ou présidentielles, car le vote est souvent perçu comme un facteur d’inclusion."

Conseil Supérieur des Programmes, Langues, littératures et cultures étrangères – Anglais, monde contemporain, enseignement de spécialité, classe terminale, voie générale, p. 15.

Scotland needs an immigration policy suited to our specific circumstances and needs. Scotland needs people to want to work here, in our businesses, our universities and in our public services. The current UK one-size-fits-all approach to immigration is failing Scotland.

The SNP will continue to seek devolution of immigration powers so that Scotland can have an immigration policy that works for our economy and society. And we will stand firm against the demonisation of migrants.

The SNP Scottish Government has published a new plan for a Scottish immigration system that protects our public services and economy. The plan sets out why a different approach is needed; how the UK government can address the challenges Scotland faces now; and how we can get on with building an immigration system that works for Scotland.

We believe the Scottish Government should have a role in deciding the ‘shortage occupation list’ – the list of occupations which have difficulties in finding suitable candidates in the UK – in order to attract the people that Scotland needs. […]

And for those that have already chosen to make Scotland their home, we want a more compassionate approach to family migration.

https://www.snp.org/policies/pb-what-is-the-snp-s-policy-on-immigration/, accessed on January, 15th 2021.

Introduction

This overview of the SNP’s (Scottish National Party) general policy regarding immigration, published on its website, is significant because it clearly emphasises Scotland’s distinctive values within the United Kingdom. It is undoubtedly to be understood that Scotland is above all different from England. We can identify three elements in this political statement which support and explain the nation’s distinctiveness:

- Scotland has specific economic, demographic and educational needs and challenges to address. They can’t be achieved because of the immigration policy that is implemented by Westminster;

- Scotland is deeply attached to the ethos of public service, and therefore rejects the privatisation of public services that has long been taking place in England;

- Scotland is philosophically different in the way it welcomes migrants; Scotland intends to set the bar higher than England in terms of attractiveness and humane attitudes towards them. This very clearly hints at the SNP’s conception of citizenship and national identity.

Political and economic elites in devolved Scotland have produced a positive – and mostly unchallenged – discourse regarding immigration to the point that Scottish society is generally presented as more open and friendlier towards migrants than its southern neighbour. Economic stability and an acute need for a demographic boost, as well as a deep-rooted Scottish humane tradition of welcoming newcomers have been the main arguments put forward by the Scottish Labour party between 1999 and 2007 and the SNP since it took over from Labour in 2007. These arguments are grounded on Scotland’s distinctive character which stems from the significant level of autonomy that Scotland has maintained thanks to its established church and its specific educational and judicial systems since (or in spite of) the 1707 Act of Union.

Immigration was one of the very contentious issues during the Brexit debate. The British conservatives promised a hard Brexit which meant that taking back control of EU immigration and withdrawing from the jurisdiction of the European Court of Justice were the top priorities. They were obviously incompatible with membership of the single market. Indeed, the EU made it clear that membership of the single market necessarily meant accepting the EU’s four freedoms – the free movement of people, goods, capital and services – and complying with the EU’s rules that regulate those freedoms. Since January 1st, 2021 and the end of the transition period, the circulation of EU people to the UK is no longer free, although there is no need of a visa for EU people who intend to stay in the UK for less than three months. It means that it is now more difficult for EU people to come and settle in the long term in Scotland. As a result of this undesired, if totally expected, turn, the SNP has relentlessly argued that the rules have changed against Scotland’s will and at the expense of Scotland’s vital demographic and economic interests, as Scotland overwhelmingly voted against Brexit and still has no say whatsoever on immigration policies elaborated by Westminster.

The SNP claims that Scotland’s democratic, demographic and economic challenges are constitutionally impossible to address in the nation’s best interests because of Brexit and inadequate constitutional arrangements (within the United Kingdom). However, things are subtler than this highly engaging political rhetoric. We would like to suggest that the arguments to which the SNP resorts to substantiate its very favourable discourse on immigration and immigrants’ rights in Scotland needs to be critically addressed, from a historical and contemporary perspective. Therefore, we would like to

- challenge the view defended by the SNP that Scotland has, contrary to the rest of the United Kingdom, a deeply rooted and long-standing tradition of welcoming migrants;

- outline the founding principles of Scottish civic nationalism in the matter of immigration in devolved Scotland;

- uncover the SNP’s intentions behind the seemingly unequivocally positive rhetoric of civic nationalism.

1. Challenging the welcoming nation

It is important to remember that Scotland has always been a nation of immigration and emigration. However, and unsurprisingly, the myth of the welcoming nation that is ingrained in the nationalist discourse is unequivocally challenged by historical facts. As in many other European countries, immigrants were generally not welcomed in Scotland with open arms and struggled to blend with the local population. While many Scots left their homeland from Glasgow in the hope of living a better life in the British colonies, many foreigners left their homelands and ended up settling in Scotland, and in particular in Glasgow, although Scotland was at first only intended to be a stage in their journey to their final destination further West.

There have been several waves of immigration in Scotland ((See T. M. Devine, The Scottish Nation 1700-2007, London, Penguin, 2012)). The first wave was domestic and is the consequence of the “Highland Clearances”, when people from the Highlands massively immigrated to Glasgow and the Lowlands, from the late 18th century to the 1850s, driven not only by large landowners who expelled small farmers from their plot of land to replace them with sheep farming (the enclosure movement), but also by hunger and very difficult living conditions. While many emigrants from the Highlands settled in Glasgow or the Lowlands, a significant number of them migrated to Edinburgh and Dundee and the British colonies.

The migration of Highlanders became massive in the 1820s and reached its peak in the 1840s and 1850s. Rather than being locked up in the factories of Glasgow, the men massively integrated the city’s police force, becoming one of its defining characteristics. The end of this first wave overlaps with the beginning of the second one, when the Great Famine forced so many Irish people to leave Ireland. Hundreds of thousands of them crossed the Irish Sea to settle in the central belt of Scotland. (Catholic) Irish immigration into Scotland lasted for more than half a century (See “Sectarisme religieux et football en Ecosse” for more details on Protestant and Catholic Irish immigration into Scotland).

Ever since, Scotland has been a land of immigration – or asylum – for a large number of communities with origins as diverse as the reasons leading immigrants to leave their homeland. Sizeable communities of Italians, Poles, Lithuanians, Pakistanis, Asians (Chinese, Malaysians and people from Hong-Kong) have come to settle in Scotland. A large number of Italians settled in Glasgow mainly between 1890 and the First World War. Lithuanian and Polish immigration was triggered by the pogroms which targeted Jewish people in Eastern Europe at the end of the 19th century.

A second wave of Polish immigration took place at the time of the Second World War. It was made up of Jews who managed to escape the Nazis and soldiers who fled Poland and formed the First Army Corps based in Scotland and comprising 40,000 soldiers. After the war, 8,000 Poles remained in Scotland. As for Pakistani immigration, it really took off after partition with India in 1947 but remained very moderate. Today, there is a small community of Asian people living in Scotland, mainly from Pakistani origin. In the same way as the other migrant communities, they experienced racism and xenophobia.

These migrant populations were not welcomed in the industrialised central belt of Scotland with open arms. People from the Highlands were the target of prejudice and racism from Lowland people, who openly despised them. For instance, The Scotsman, Edinburgh’s quality paper, wrote in 1846 that Highlanders were morally and intellectually inferior to people from the Lowlands ((Cited in Mary Edward, Who Belongs to Glasgow?, Edinburgh, Luath Press, 2008, p. 26)).

Unsurprisingly, the Scottish local population was often very reluctant, not to say strongly opposed, to the establishment and growth of foreign communities in times of economic trouble and contraction of the labour market. The Irish formed substantial working-class communities in the industrial areas and were considered as a serious threat on the labour market, even if they were mostly confined to unskilled and low-skilled occupations. They were often accused of being strike-breakers by agreeing to replace strikers at lower hourly rates. In 1923, the xenophobic attitude towards Roman Catholic Irish was endorsed by the Church of Scotland which published a pamphlet entitled The Menace of the Irish Race to Our Scottish Nationality:

They cannot be assimilated and absorbed into the Scottish race. They remain a people by themselves, segregated by reason of their race, their customs, their traditions, and, above all, by their loyalty to their Church, and gradually and inevitably dividing Scotland, racially, socially, and ecclesiastically.

The problem, therefore, that has been remitted to the Committee for consideration is almost exclusively an Irish problem; and though recognition should be made of a certain number of Poles in the coal-mining districts, the fact remains that this is a question arising out of the abnormal growth of the Irish race in Scotland.

General Assembly of the Church of Scotland, The Menace of the Irish Race to Our Scottish Nationality, Edinburgh, W. Bishop, 1923, p. 1-2. https://dokumen.tips/documents/menace-of-the-irish-race-to-our-scottish-nationality.html

In the Gorbals, a central neighbourhood of Glasgow where many Jewish and Irish Catholic immigrants settled, antisemitism remained moderate, but accounts from Jewish inhabitants show that Jewish children were persecuted by other children, especially between the two wars ((See Evelyn Cowan, Spring Remembered - A Scottish Jewish Childhood, Penicuik, Southside Publishers, 1974. See also Chapters 2 and 4 of Fabien Jeannier's PhD, The Dear Green Place ? Régénération urbaine, redéfinition identitaire et polarisation spatiale à Glasgow - 1979-1990. https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-00798825)). Jewish people found it very difficult to rent houses in other parts of the city. There is also a long and documented history of sectarian prejudice between Protestants and Roman Catholics fuelled by their respective Churches, in particular in the most industrialised areas of the country ((See Steve Bruce et al, Sectarianism in Scotland, Edinburgh, EUP, 2004.)).

The Church of Scotland expressed its intolerance towards Jewish people during the interwar period in the same way as it did towards Catholics. In 1938, James Black, Moderator of the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland gave a speech entitled "The Jewish Enigma" which left no doubt as to the position of the Church of Scotland:

There are only two ways to treat the Jews, and they are to fight them or to convert them, and Britain’s desire is not to fight them but to see them converted to accepting the pure and unsophisticated principles of the Christian religion as their faith.

Cited in Billy Kay (ed.), Odyssey, Voices from Scotland's Recent Past, Edinburgh, Polygon, 1980, p. 119.

The two world wars led to restrictive legislation for immigrants from countries at war with the UK. During the First World War, the shops owned by Jewish people coming from the countries at war with the UK were vandalised. Italian immigrants did not compete with local people on the labour market as they were mainly employed in or managed shops such as barber shops, ice-cream parlours or cafés and restaurants. However, they were accused by the Church of Scotland of perverting Scottish youth as the shops were opened on Saturdays and Sunday mornings. During the Second World War, the shops run by Italian people were the target of hostile and violent demonstrations. Italian men and women aged between 16 and 60 were arrested and detained, even when they had spent their entire life in Scotland.

The Scottish National Party (SNP) contributed to the racist and xenophobic ideas and behaviours of the times. The SNP was founded in 1934 during the first phase of Scottish cultural and political nationalism which spanned the interwar years and is often described as the Scottish Renaissance. It was a period of flowering Scottish culture. At its founding, the SNP was indisputably dominated by racist and xenophobic ideas ((See Keith Dixon, « Le pari risqué des nationalistes écossais : l’indépendance ou rien ? », Politique étrangère, 2013, pp. 51-61.)).

The leading figures of the SNP at the time were Hugh MacDiarmid and Andrew Dewar Gibb who, however, represented two very distinct currents within the SNP, to say the least. MacDiarmid, an intellectual and poet who supported a form of socialist republican nationalism, famously expressed his distaste for England when listing Anglophobia as one of his favourite hobbies in his Who’s Who entry. As for Andrew Dewar Gibb, he came from a middle-class Tory background and supported a conservative and imperialist vision of Scottish nationalism. He deeply resented the presence of Irish immigrants in Scotland, whom he believed to be a menace for Scottish society. Although he was cautious enough not to express publicly the full breadth of his views, he abhorred socialist and communist ideas, which he believed were a bigger threat than fascism and Nazism. In his private correspondence, he wrote about his admiration for Hitler and Mussolini.

The second phase of Scottish political nationalism, which arguably opened with the SNP by-election victory in Hamilton in November 1967, has been marked by a major shift in perspective regarding immigration, sweeping aside the racist and xenophobic stances of the previous period. In the 1990s, Alex Salmond (leader of the SNP from 1990 to 2000 and 2004 to 2014) understood the party’s need to be more inclusive and representative of Scotland’s diversity. This led to the creation within the SNP of such groups as New Scots, appealing to people who were not born in Scotland, and Scots Asians for Independence, launched by Bashir Ahmad at the SNP conference of 1995. Bashir Ahmad, who was born in India before Partition, was to be elected the first Asian and Muslim member of the Scottish parliament in 2007. Alex Salmond also condemned the emergence of anti-English groups such as Settler Watch and Scottish Watch while enabling English-born figures to rise in the party.

2. Civic Nationalism and Immigration in devolved Scotland

The arrival of asylum seekers in huge numbers in Scotland is contemporary of devolution, as it dates back to 1999, when the British government decided to implement a dispersal scheme in order to alleviate the burden of accommodating them from the local authorities in the south east of England. It has had major repercussions in Glasgow, the only local authority where asylum seekers have been sent to live in empty local council houses located on the fringes of the city. It should be noted that these totally unprepared massive arrivals of asylum seekers in the city of Glasgow at the beginning of the 2000s also led to quite hostile reactions from some local communities ((See Fabien Jeannier, “La politique britannique de dispersion des demandeurs d’asile depuis 1999 : l’exemple de la ville de Glasgow”, Miranda, 2014, en ligne: https://journals.openedition.org/miranda/5881)).

The arrival of economic migrants from Eastern Europe is an even more recent phenomenon. It is linked to the admission of A8 countries into Europe (The Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Slovakia and Slovenia joined the EU in 2004) and Bulgaria and Romania in 2007. These two rather broadly-defined categories of migrants – economic EU migrants from Eastern Europe and asylum seekers/refugees – were the main targets of particularly aggressive anti-immigrant discourses during the Brexit campaign, in particular in England.

Syrian people are the most recent and substantial wave of asylum seekers coming to Scotland. In September 2015, the British Prime Minister and Scotland’s First Minister launched the Syrian Vulnerable Persons Resettlement Scheme. The Prime Minister committed to resettling 20,000 Syrian refugees in the UK and to providing financial aid in Scotland. By November 2017, 2,000 Syrian refugees had settled in Scotland. By early 2020, there were over 3,000 individuals in all 32 of Scotland’s local authority areas.

2.1 The constitutional and political context

The complex British constitutional context is characterised by the devolution of powers to regional governments in Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales ((See Nathalie Duclos, L’Écosse en quête d’indépendance ? Le référendum de 2014, Paris, Presses de l’Université de Paris-Sorbonne, 2014. See also Stéphanie Bory and Timothy Whitton, « The May 2016 Devolved Elections in Scotland, Wales, Northern Ireland and London: Convergences and Divergences », Revue Française de Civilisation Britannique, XXII-4 | 2017, DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/rfcb.1561.)). In Scotland, devolution is the result of a long process and repeated claims for independence, which did not cease with access to self-government. Devolution is an evolving process and new extended powers have been devolved to the Scottish parliament since the SNP came to office in 2007. Despite the failure of the referendum for the independence of Scotland in September 2014, the SNP was returned to power in the May 2016 parliamentary elections and won the May 2017 local elections. The next Scottish parliamentary elections, which are more than likely to be won by the SNP, are due in May 2021.

The successive Labour and SNP governments have had various degrees of diverging and conflicting views on immigration with the British conservative governments. Immigration and nationality are one of the key reserved powers retained by Westminster. As a consequence of the current constitutional arrangements, the devolved Scottish governments have had very little, if any, influence on the making of British immigration policy. However, it is generally assumed that they would have implemented an incentive policy of inward mobility regarding European and non-European migrants, as well as asylum seekers, had it got the devolved powers to do so.

2.2 Common values and institutions in a multicultural state

It is essential to point out that political nationalism in Scotland as it is defended by the SNP is not the expression of a specific identity based on ethnic, cultural, religious, territorial or linguistic preferences, as it can be observed in other (European) minority nations. Nor is it fuelled by racist and/ or xenophobic ideas as it used to be in the 1930s. The SNP’s general political statement on its website tells us that Scottish political nationalism is essentially a matter of promoting an approach to social and economic issues for Scotland that is (radically) different from the one implemented by the successive British Tory (and to a lesser extent Labour) governments and elected parliaments at state level:

The SNP is committed to making Scotland the nation we know it can be. Our vision is of a prosperous country where everyone gets the chance to fulfil their potential. We want a fair society where no-one is left behind.

https://www.snp.org/our_vision, accessed on January, 19th, 2021.

In the nationalist discourse, the (re)-building of the Scottish nation implies the recognition of the benefits of multiculturalism in an independent Scotland which would be able to pursue economic, social, environmental and international relations policies based on radically different values from those defended by the British governments since Margaret Thatcher's conservative premiership. In the eyes of the SNP, the independence of Scotland is above all a question of democracy, for more prosperity and well-being and is the best, if not the only possible, way for Scotland to be true to its nature.

In stark opposition to traditional right-wing political parties, Scottish political nationalism defines Scotland “first as a civic nation in which citizenship is dependent on a shared territory and a willingness to live together, rather than on common origins; secondly, as a land where the people are sovereign and hold their destinies in their own hands, and in their hands only; and thirdly, as a commonwealth (or “common weal”) where people hold dear welfarist values and policies” ((Nathalie Duclos, « The SNP’s Conception of Scottish Society and Citizenship, 2007-2014 », Revue Française de Civilisation Britannique, XXI-1 | 2016, DOI : 10.4000/rfcb.856, p. 9.)).

Implementing an economic and social policy that is fairer and more inclusive than the policies implemented in the rest of the United Kingdom by the central government obviously applies to immigration. The SNP promotes the idea that an independent Scotland would not aim to prevent migrants from settling in Scotland, but encourage their arrival and, in the specific case of asylum seekers, ensure a fairer, more humane and more efficient process. In this respect, the SNP wants Scotland to distinguish itself very clearly from England, where migrants, whether they are asylum seekers, refugees or economic migrants, have had to deal with outright hostility and fear in certain places and more and more punitive public policies. This is undoubtedly an exception in the current landscape of European immigration policies and debates.

2.3 Integration from Day One

The Scottish nationalist government's position, exposed in 2015 by Secretary of State for Social Justice Alex Neil, is unsurprisingly completely in line with the ambition to strengthen Scotland's reputation as a country with a tradition of welcoming and integrating migrant populations. It is clear regarding the specific case of asylum seekers. While the British government's bills aimed at reducing the rights of rejected asylum seekers and facilitating the eviction of illegal migrants from their homes, Alex Neil said:

Destitution should never be an outcome of the asylum system. When we talk about asylum seekers, we are not talking about objects, we are first and foremost talking about vulnerable people, families, men, women and their children – people who have often been through great trauma and who deserve to be treated fairly and equally and with dignity and respect.

In Scotland we want to build a fair and equal country that we can all be proud of. If we had powers over immigration, we would take a humane approach to asylum seekers and refugees in line with our commitment to fairness and equality, and of course upholding human rights. We would take action to ensure that asylum seekers do not face destitution and humiliation by implementing a new system of support. We strongly believe that those refused asylum for whatever reason should be treated with fairness and compassion.

https://www.webarchive.org.uk/wayback/archive/20161101030434/http://news.gov.scot/news/inhumane-approach-to-refused-asylum-seekers, accessed on January, 21st 2021.

Although immigration is a reserved power of Westminster, asylum seekers and refugees use, on a daily basis, services (education, health, social support, etc.) that fall within the responsibilities devolved to the Scottish Parliament ((The other devolved responsibilities include the economy, justice, rural affairs, housing, environment, equal opportunities, consumer advocacy and advice, transport and taxation while the powers reserved to the UK Government comprise immigration, the constitution, foreign policy and defence.)). They remain, however, dependent on the central state’s regulations for their rights to living and accommodation allowances.

Housing is one of the key issues raised by the current constitutional arrangements, as it remains within Westminster’s remit while the asylum application is pending but falls to the Scottish Government when refugee status is granted to the asylum seeker, making the transition period particularly sensitive. The fact that immigration has remained a reserved power to Westminster has generated contradictions and conflicts between the central state and the devolved institutions which not only singularly complicate the task of those involved in the reception of asylum seekers, but also give substance to the assumption that the dispersal policy lacks coherence and was primarily devised to serve the interests of the south of England.

These contradictions and conflicts between the central state and the devolved institutions are not new to the nationalist administration. As a matter of fact, there is no real nationalist specificity with regard to asylum seekers and refugees. When the Scottish Labour governments (1999-2007) were suddenly faced with a large and rather unprecedented influx of asylum seekers (there were some 10,000 asylum seekers and refugees in Glasgow in the early 2000s), they developed a humane approach that aimed at contrasting with British Labour’s dissuasive approach at state level.

In January 2002, the Scottish Labour government set up the Scottish Refugee Integration Forum, chaired by Iain Gray, Labour Minister for Social Justice, to bring together Scotland's statutory and voluntary agencies to support refugees more effectively. The remit of the Scottish Refugee Integration Forum was to propose an action plan on education, housing, safety and access to justice, health, employment and training to facilitate the integration of asylum seekers in Scotland and to promote a positive image of asylum seekers and refugees within communities and in the media. The discourse then was very similar to the nationalist discourse held 15 years later:

There have clearly been problems in the past as asylum seekers and refugees have settled into their host communities. However, I am committed to ensuring that we in Scotland continue with our strong tradition of welcoming and integrating asylum seekers and refugees fleeing from oppression and persecution.

The forum will work closely with refugees and community groups and build on relationships with organisations such as the Scottish Refugee Council, the Scottish Asylum Seekers Consortium and local authorities. Its overarching aim will be to help ensure that asylum seekers who achieve refugee status will be assisted to integrate into local communities as smoothly as possible.

Iain Gray, https://www.lgcplus.com/archive/refugee-integration-forum-22-01-2002/ 22 January 2002, accessed on January 21st, 2021.

When they came to power in 2007, the nationalists did not question Labour's humanist vision for asylum seekers and refugees. Like Labour, they emphasised Scotland's long tradition of welcoming asylum seekers. Very symbolically though, and although it did not have any practical means of action since it is Westminster’s reserved power, the SNP government promised during the campaign for Scottish independence in 2014 to bring dawn raids to an end and close the Dungavel immigration detention centre. This centre had been the object of militant campaigns denouncing the internment of children – a practice that ceased in 2010 – as well as the inhuman conditions and length of detention to which migrants awaiting deportation are subjected. Dungavel Immigration Removal Centre is located in South Lanarkshire near the town of Strathaven. It is operated by the American private prison firm GEO Group, on behalf of Border Force, the law-enforcement command within the Home Office which is responsible for frontline border control operations at air, sea and rail ports in the United Kingdom. It is the only such facility in Scotland and is still in operation.

In the very sensitive case of asylum seekers, the Scottish Government emphatically claims that it considers that integration begins when the asylum seeker arrives on Scottish soil, while the British government considers that it begins when they are granted the status of refugee. This makes a critical difference to asylum seekers, as it may have a significant impact on their rights – the financial and accommodation support they are entitled to claim. This was unambiguously stated at the end of 2013, shortly after the publication of the white paper Scotland's Future, when the Scottish government set out its strategy for supporting integration into Scottish society for asylum seekers and refugees for the period 2014-2017:

The vision behind this strategy is for a Scotland where refugees are able to build a new life from the day they arrive in Scotland and to realise their full potential with the support of mainstream services; and where they become active members of our communities with strong social relationships.

Scottish Government, New Scots, Integrating Refugees in Scotland’s Communities, 2013, p.6.

And it was clearly reaffirmed when the Scottish Government published the second New Scot strategy from 2018 to 2022. The plan is supported by the following overarching vision:

For a welcoming Scotland where refugees and asylum seekers are able to rebuild their lives from the day they arrive. The New Scots strategy sees integration as a long-term, two-way process, involving positive change in both individuals and host communities, which leads to cohesive, diverse communities.

Scottish Government, New Scots Refugee Integration Strategy 2018 – 2022, 2018, p.10.

I am proud that Scotland has become home to people from all over the world seeking safety. Scottish Ministers have always been clear that people who seek asylum in Scotland should be welcomed and supported to integrate into our communities from day one. When refugees and asylum seekers arrive, they need understanding, support and hope for their future; and children should be able to be children, whether they arrive with their family or on their own.

Angela Constance, Cabinet Secretary for Communities, Social Security and Equalities Secretary in Scottish Government, New Scots Refugee Integration Strategy 2018 – 2022, 2018, p.10.

There are five guiding principles to the New Scots approach. The first one is “Integration from day one”, while the second one is “A right based approach”:

Integration From Day One

The key principle of the New Scots strategy is that refugees and asylum seekers should be supported to integrate into communities from day one of arrival, and not just once leave to remain has been granted. Integration is the long-term, two-way process, which enables people to be included in society. Evidence shows that if people are able to integrate early, particularly into education and work, they make positive contributions in communities and economically. As with the first New Scots strategy, the Indicators of Integration framework underpin the holistic approach being taken. This framework recognises the whole person and the impact which interdependent factors can have on how a person feels, their health and wellbeing and their opportunity to participate in society and pursue their ambitions.

A Right Based Approach

The New Scots strategy aims to empower people to know about their rights and to understand how to exercise them. We support refugees and asylum seekers because it is the right thing to do; people should be able to live safely and realise their human rights. The strategy takes a holistic, human rights approach to integration that reflects both the formal international obligations the UK has and the long-standing commitment of successive Scottish Governments, and of local government in Scotland, to address the needs of refugees and asylum seekers on the basis of principles of decency, humanity and fairness.

Scottish Government, New Scots Refugee Integration Strategy 2018 – 2022, 2018, p.11-12.

In line with the Scottish government’s vision, when giving evidence to the Scottish Parliament’s Equalities & Human Rights Committee, in an inquiry into destitution and asylum on January 10th, 2018, Angela Constance, Cabinet Secretary for Communities, Social Security and Equalities Secretary spoke about the “outrage” of UK’s approach to asylum and stressed the destitution and human misery which are created by the UK Government’s “appalling” approach to asylum seekers and refugees:

It is an outrage that the UK Government has imposed an asylum system that causes human misery. The fact that people fleeing war and terror, who have sought refuge in the UK, can end up penniless and susceptible to exploitation is appalling.

Vulnerable people, particularly children, are being badly let down by the UK Government’s broken asylum system – with their human rights ignored. […]

We will continue to keep compassion and human dignity at the heart of our work with asylum seekers and refugees – qualities that are totally lacking in the approach of the Home Office.

https://www.gov.scot/news/a-broken-asylum-system/, 20 Apr 2017, accessed on January 21st 2021

In the nationalist political discourse, Scotland is presented as a country where migrants are treated in a more humane way than in the rest of the United Kingdom. The nationalists consistently emphasise Scotland’s reputation as a haven for migrants to legitimate their political stance – although historical facts show that this is quite debatable. However, it is essential to point out that the SNP’s very favourable position on immigration is mitigated by the wider picture of Scottish society. Scotland is no exception to many other European countries, where immigration is a very sensitive, debated and contested issue (See Eve Hepburn and Ricard Zapata-Barrero, The Politics of Immigration in Multilevel States. Governance and Political Parties, Basingstoke, Palgrave Macmillan, 2014, p. 241-260). There is a growing discrepancy between Scottish political and economic elite and the wider society about immigration, whether it is from EU countries or asylum seekers – Scottish attitudes towards immigration are actually not so different from English attitudes ((See the report by the Migration Observatory: https://migrationobservatory.ox.ac.uk/resources/reports/scottish-public-opinion/ or https://fpc.org.uk/divided-kingdom-how-do-attitudes-towards-immigration-vary-based-on-demographic-differences-and-voting-preferences/)).

It is therefore not surprising that a closer look at policy papers should reveal that the SNP is adamant that the “free movement of people does not mean the unrestricted movement of people” (The Scottish Government, Scotland’s Population Needs and Migration Policy: Discussion Paper on Evidence, Policy and Powers for the Scottish Parliament, Edinburgh, The Scottish Government, 2018, p. 28). Its 2018 policy paper Scotland’s Population Needs and Migration Policy is equally unequivocal, and analyses good practice from countries where different systems of points-based processes have been implemented to select immigrants:

In the short term, the priority for the Scottish Government is a mechanism to attract high value migrants who can contribute to Scotland. This could operate under the UK immigration system with powers devolved to Scottish Ministers, accountable to the Scottish Parliament, to determine and vary criteria and thresholds according to Scotland’s needs? This might include, for instance salary, assets, education, skills, age, language level of affinity with Scotland in order to ensure that the characteristics and volume of migrants entering the country under this route would be in keeping with defined economic and demographic requirements.

The Scottish Government, Scotland’s Population Needs and Migration Policy: Discussion Paper on Evidence, Policy and Powers for the Scottish Parliament, Edinburgh, The Scottish Government, 2018, p. 34.

This is not new, as the nationalist government was already unequivocal about his intentions to set up a points-based system of immigration to attract talented immigrants in the 2013 white paper Scotland’s Future preparing for independence (The Scottish Government, Scotland’s Future. Your Guide to an Independent Scotland, Edinburgh, The Scottish Government, 2013, p. 270).

Conclusion: Beyond the rhetoric of civic nationalism

As it is presented by the nationalist government, immigration in Scotland is a demographically, economically and socially crucial issue because of an acute need for a demographic boost in the long term. It is underpinned by a deep-rooted Scottish humane tradition of welcoming newcomers, and wrapped in the benefits of multiculturalism and civic nationalism. There is a strong emphasis on Scotland’s compassionate approach towards asylum seekers in particular, miles away from the English punitive approach. It seems undeniable that Scottish civic nationalism appears as a real opportunity for migrants who are looking for a safe place to go on with their lives.

As immigration is a key issue in the SNP’s independence project, it has to be a key element of its political discourse. However, beyond the rhetoric of civic nationalism, a close reading of policy papers shows that the SNP’s view on the matter is first and foremost supported by very pragmatic and economy-driven reasons. After all, Scotland is an ageing nation that critically needs new skills and working population. Natural change is projected to be negative in Scotland each year for the next 25 years and all of the projected increase in Scotland’s population over the next 25 years will be due to migration.

The current constitutional arrangements mean that the successive Scottish governments have had very little, if any, influence on the British immigration policy since devolution became effective in 1999. As a result, they have never had any serious opportunity to deliver a substantially distinctive policy from the rest of the UK in the matter. Thus, to put it bluntly, we can’t tell to what extent the SNP government would have effectively implemented a significantly different immigration policy, and how it would have impacted Scottish economy and society. We still don’t know how a nationalist government will act with full powers on immigration and citizenship when facing strong opposition from the public opinion and subsequent potential electoral setbacks.

Until Scotland regains full powers on immigration policy and acts accordingly, we simply can’t take the SNP’s arguments for granted. Beyond the “objective” demographic and economic reasons, the political discourse on human rights is not entirely convincing, when there is no real perspective of dealing with immigration first-hand in the short term. Surely the SNP can’t be blind to Scottish society’s growing opposition to immigration. We might therefore wonder to what extent striking the sensitive chord of compassion is only shrewd political tactics to make immigration more acceptable to a population that is not overwhelmingly favourable to it and to substantiate a political discourse that is significantly different from UK wide parties such as Labour and the Conservative party.

Notes

Further Reading

CAMP-PIETRAIN, Edwige. 2014. L’Ecosse et la tentation de l’indépendance. Villeneuve d’Ascq : Presses Universitaires du Septentrion.

DIXON, Keith. « Les Liens du sang : Quand les droites radicales européennes influençaient un nationalisme écossais émergent (1918-1939) », in Philippe Vervaeke, À droite de la droite : Droites radicales en France et en Grande-Bretagne au XXe siècle. Villeneuve d’Ascq : Presses Universitaires du Septentrion. http://books.openedition.org/septentrion/16194

DUCLOS, Nathalie. 2016. « The SNP’s Conception of Scottish Society and Citizenship, 2007-2014 ». Revue Française de Civilisation Britannique, volume 21, numéro 1. DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/rfcb.856

EL FEKIH SAID, Wafa. 2018. « Reconstruction and Multiculturalism in the Scottish Nation-Building Project ». Études écossaises, volume 20. DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/etudesecossaises.1418

JEANNIER, Fabien. 2018. « Les incertitudes écossaises, entre autonomie et indépendance », in François Dubet (dir.), Politiques des frontières. Paris : La Découverte, pp. 50-70. https://www.cairn.info/politiques-des-frontieres--9782348040740-page-50.htm

--. 2014. « La politique britannique de dispersion des demandeurs d’asile depuis 1999 : l’exemple de la ville de Glasgow ». Miranda, volume 9. DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/miranda.5881

REVEST, Didier. 2016. « Are the commitment to Scottish independence and the Scottish National Party’s surge evidence of a clash of values between Scotland and England? ». Observatoire de la société britannique, volume 18. DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/osb.1807

The Scottish Government. 2018. Scotland’s Population Needs and Migration Policy: Discussion Paper on Evidence, Policy and Powers for the Scottish Parliament. Edinburgh : The Scottish Government, https://www.gov.scot/publications/scotlands-population-needs-migration-policy/

The Scottish Government, Refugees and asylum seekers : https://www.gov.scot/policies/refugees-and-asylum-seekers/

Glasgow Refugee Asylum and Migration Network (GRAMNet) : https://gramnet.wordpress.com/ ; https://www.gla.ac.uk/research/az/gramnet/

Migration Scotland : http://www.migrationscotland.org.uk/

Scottish Refugee Council : https://www.scottishrefugeecouncil.org.uk/

Documents for class use

In: The Scottish Government, Scotland’s Population Needs and Migration Policy: Discussion Paper on Evidence, Policy and Powers for the Scottish Parliament, Edinburgh, The Scottish Government, 2018.

- Ministerial foreword, p. 3-4. [Télécharger le document]

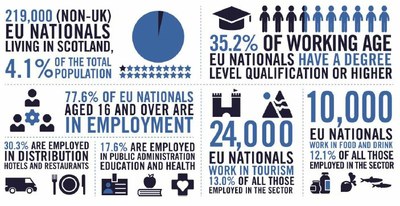

- Infographic on the contribution of EU citizens to Scotland, p.32.

- Box 8 – Asylum, p. 40

In: The Scottish Government, New Scots: Integrating Refugees in Scotland’s Communities. Year 1: implementation progress report, Edinburgh, The Scottish Government, 2015.

- Needs of Dispersed Asylum Seekers, stakeholder views, p. 19. [Télécharger le document]

- Education, stakeholder views, p. 42-43. [Télécharger le document]

Govan Community Project: https://www.govancommunityproject.org.uk/about.html

Scottish Refugee Council stories: https://www.scottishrefugeecouncil.org.uk/category/stories/

Pour citer cette ressource :

Fabien Jeannier, Scottish Civic Nationalism: An Opportunity for Migrants?, La Clé des Langues [en ligne], Lyon, ENS de LYON/DGESCO (ISSN 2107-7029), mai 2021. Consulté le 14/01/2026. URL: https://cle.ens-lyon.fr/anglais/civilisation/domaine-britannique/irlande-et-ecosse/scottish-civic-nationalism-an-opportunity-for-migrants

Activer le mode zen

Activer le mode zen