The Perception of Male Homosexuality in Great Britain from the 19th century to the Present

Cet article a été rédigé dans le cadre d'un stage de Master.

Introduction

“Homosexuality has existed throughout history, in all types of society, among all social classes and peoples, and it has survived qualified approval, indifference and the most vicious persecution. But what have varied enormously are the ways in which various societies have regarded homosexuality, the meanings they have attached to it, and how those who were engaged in homosexual activity viewed themselves.” (Weeks, 2)

Jeffrey Weeks makes an important point about the understanding of the nature of homosexuality: it is a universal phenomenon and a tendency that manifests itself in human species. The attraction between individuals of the same sex has always been there, even though different terms were used in different periods and in different cultures:

“Male inverts in classical Rome were termed cinaedi, in medieval court culture 'catamites', in eighteenth-century London bars 'mollies', in living memory 'fairies’” (Mills, 257)

This article will examine the ways in which homosexuality has been perceived in Great Britain, that is the ways people have been defined on the basis of their sexual identity as well as the limitations such definitions have placed on one’s identity. Religious, legal and medical frameworks also had an impact on these perceptions and on how we understand homosexuality in the British context today. The article will focus on the perception of homosexuality in Great Britain from the 19th century up to the contemporary period, making references to other parts of the world as well as other periods of time. The works of Jeffrey Weeks (Coming Out: Homosexual Politics in Britain from the Nineteenth Century to the Present, 1977), Sebastian Buckle (The Way Out: A History of Homosexuality in Modern Britain, 2015) and Annamarie Jagose (Queer Theory: An Introduction, 1996) are our main points of reference and the article draws heavily on a talk given by Jeffrey Weeks at the LGBT centre on 3rd April, 2019 in Lyon ((https://cle.ens-lyon.fr/anglais/civilisation/domaine-britannique/the-gay-liberation-front-and-queer-rights-in-the-uk-a-conversation-with-jeffrey-weeks)).

The article will focus primarily on gay men, because lesbian reality takes a completely different trajectory and needs to be treated as a separate subject. The main reasons for this difference are the lack of sanctions for lesbian sex acts as well as a lack of visibility of these women. Both the Gay Liberationist and Feminist Movements manifested a latent fear of the ‘masculine lesbian’ taking over the discourse of the groups aforementioned; for this reason, lesbians remained outcasts in both, and were forced to remain distinct from both the homosexual as well as the feminist cause.

To understand how homosexuality has been perceived in Great Britain since the 19th century, it is important to note that homosexual sex acts remained a crime from 1885 to 1967 in that country. When the 1553 Buggery law was passed in England, even though persecution of sodomy moved from the religious domain into the legal domain, the reasons for persecution remained the same. This law had an impact on the perception of homosexual individuals in society, which will be discussed in later sections. In History of Sexuality Volume 1, Foucault traces how homosexuality never ceased to pose a problem in society: what evolved was the framework of persecution, from religious to legal to finally medical institutions. All found a way to state that homosexuality was ‘unnatural’ and needed to be punished and/or treated.

1. 19th century: The Emergence of Homosexuality as a Type of Identity

1.1 Early Definitions of Homosexuality and the Wilde Trials

“Every generation needs its own heroes, and for three or four generations of gay men Wilde seemed to more than fit the bill.” (Hugh David, 5)

The word ‘homosexuality’ began to be used in the late 19th century to designate a newly created concept, a type of identity, just as, for instance, a ‘housewife’ or a ‘prostitute’ in this period. Prior to this, there did not exist a specific category to define the sexual identity of a person attracted to their own sex. There were a number of derogatory terms used to describe homosexuals at that time (such as “pansy”, for instance). “[These names] are not just new labels for old realities: they point to a changing reality, both in the ways a hostile society labelled homosexuality, and in the way those stigmatized saw themselves.” (Weeks, 3) This new notion had its roots in the Hebraic and Christian traditions, and therefore had the concept of guilt deeply embedded in the experience of being a homosexual (Weeks, 4).

In the 19th century (and continuing well into the 20th century), homosexuality was a matter of changing moral standards, and the public opinion on the subject was extremely negative: homosexuality symbolised decadence and an increase in licentious behaviour that needed to be controlled. The stringent laws against homosexuality were therefore welcome in the public opinion and were considered the “guardian of the righteous” (Weeks, 11)

For the moral purity campaigners of the 1880s, prostitution and homosexuality were a matter of equal concern: they were markers of a society’s degrading morals. The root cause of both these ‘social evils’ was said to be the uncontrollable lust of men, which was the “breeding ground of both prostitution and homosexuality” (Weeks, 16, 18). Robert Peel, the then British Prime Minister, used the words “‘the crime inter Christianos non nominandum’ (the crime not to be named among Christians)” (Weeks, 14). His remark brings together the force of the British state as well as religion to declare homosexuality an abomination. According to Weeks, “’sins of the flesh’ […] threatened self and nation” (Weeks, 17) at that time, which shows how the very idea of a British nation was threatened by homosexuality, and thus it needed to be dealt with seriously.

Manliness and patriotism were the virtues young boys were supposed to possess; as a stark opposite to this ideal was homosexuality, a mark of effeminacy and corrupt morals tarnishing the social fabric (Weeks, 17). The armed forces were stricter in terms of penalisation of homosexuality in the 19th century than the laws that applied to the general public: this was perhaps because they were a symbol of patriotism and masculinity for the country (Weeks, 13). The usual punishment of homosexuality was death sentence in the armed forces, and this sheds light on the extent to which homosexuality was perceived as a danger. It is interesting to note that while the death penalty had been abolished for many other crimes, it was maintained for homosexual sex acts.

The usual approach to homosexuality in the 19th century (and even in the first half of the 20th century to some extent), was to cover up the issue as and when there were cases that came in the limelight. However, with the prosecution of Oscar Wilde for homosexuality, the subject was openly talked about for the first time, even in the press. Wilde was an important personality and the scandals around him made a lot of noise. His trials, therefore, created a “public image for the homosexual” (Weeks, 21).

Oscar Wilde never denied having sexual encounters with men. In his case, “posing” as a homosexual “was enough” to be qualified as a criminal (Weeks, 14). His name became “a synonym for folly” in this period (Weeks, 21). What followed the trials was the emergence of a systematic practice of blackmailing homosexual ‘sex offenders’. Such an exposure could lead to dishonour or a prison sentence or both for a homosexual individual (Weeks, 11).

1.2. Homosexuality as a Subculture

In the second half of the 19th century, legal discourse against homosexuality began to be slowly replaced by medical discourse. Onanism and homosexuality were treated with equal severity, and homosexuality in particular was seen as “‘the secret sin’ which has been learned at a private school, imported to a public school, and there taught to the youngest boys, [and which] will produce the more fashionable vices of the larger society.” (Edward Lyttleton cited in Weeks, 25). This belief was in line with the 1860s debate about ‘innate’ and ‘acquired’ traits, which meant by corollary that homosexuality was innate in some individuals (and these were the cases beyond help), while the others followed the decadent culture prevalent at the time (Weeks, 25).

An important work that shed light on the understanding of the subject of homosexuality in this period is Richard von Krafft-Ebing’s Psychopathia Sexualis (1886), that classified homosexuality as a pathological condition (Weeks, 26). Parallel to this, there emerged a biological explanation on the subject, which claimed that homosexuality originated from a stunted individual development and was a manifestation of moral insanity (Weeks, 27). These understandings had a direct impact on the perception of homosexuality in the 19th century and for a few decades later as well.

To cite an example, J.A. Symonds described homosexuals in the following manner: “lusts written on his face…pale, languid, scented, effeminate, oblique in expression” (cited in Weeks, 37). This was the stereotype in the minds of the general public, which put homosexual individuals at the receiving end of the violence of societal structures, especially in the context of the laws against homosexuality at the time.

To counter oppression and affirm their identity, some queer people developed their own ways of dressing up, their own language, their separate ways of socialisation as well as concepts to define their identity. This gave them a strong sense of belonging to the community (Weeks, 33). Jeffrey Weeks defines this as the ‘homosexual sub-culture’:

“Homosexuality has everywhere existed, but it is only in some cultures that it has become structured into a sub-culture.” (Weeks, 35)

Camp Aesthetic

Camp aesthetic has often been associated with the homosexual community because it originated in the homosexual subculture. As Susan Sontag points out in her book Notes on Camp, this sensibility is difficult to define. But in general, the term refers to the style of the community with their own code words, their own sense of dressing and other cultural markers that emerged. “Camp is esoteric – something of a private code, a badge of identity even, among small urban cliques” (Sontag, 1).

Mark Booth defines ‘camp’ as being an aesthetic of the margins. Since ‘camp’ originated in a subculture and not the mainstream culture, its status was marginal but it eventually became part of the mainstream as it grew more and more popular. Instead of symbolising sexual defiance, it was appropriated by all kinds of subversive cultures in order to present a challenge to the dominant culture. Another perspective offered by Umberto Eco points to the fact that the camp aesthetic became a symbol of elite culture, which aimed to redeem what was considered to be bad taste by mainstream culture:

« Le goût Camp naît comme signe de reconnaissance entre les membres d'une élite intellectuelle, si sûrs de leurs goûts raffinés qu'ils peuvent décider de la rédemption du mauvais goût d'hier, sur la base d'un amour pour le non-naturel et l'excessif – et ils renvoient au dandysme d'Oscar Wilde » (Eco, 407).

In the 1960s, due to its association with the homosexual community, camp was a derogatory term but this tendency has evolved since then. Now it signifies a culture of the elite, which is deliberately flamboyant and is meant to provoke and to question the ‘norm’.

2. 20th century: Homosexuality as a Threat to Society

2.1 Social Problem, Mental Disease or Both?

In the 1930s, the report of the Mental Deficiency Committee viewed homosexual organisations as the “social problems group” (Waters, 692). In this period and well into the next two decades, homosexuality was seen as a social problem, and was put in the same category as prostitution (Waters, 692-693). A 1995 statement by the British Medical Association’s statement affirms the prevalence of this idea:

“The public opinion against homosexual practice is a greater safeguard [than law], and this can be achieved by promoting in the minds, motives and wills of the people a desire for clean and unselfish living…” (cited in Weeks, 30)

The words “clean” and “unselfish” underline a continued belief in the opinion of the 19th century that homosexuality is a reflection of “public-school ‘immorality’” (Weeks, 16) and of an uncontrolled male lust that is the root cause of many social problems in society.

In addition to this, the second half of the 20th century saw a transition from the legal prosecution of homosexuality to ways of ‘healing’ homosexuality: psychopharmacological drugs began to market ‘cures’ for the ‘condition’. By this time, homosexuality had been firmly classified as an illness (Weeks, 30). As a result, ‘aversion therapy’, that had been initially devised to combat alcoholism, was used to ‘cure’ homosexuality in the 1960s; it involved electric shocks among other methods of treatment.

2.2 Gay Liberation Front 1970-72

The publication of the Wolfenden report in 1957 (which asked for the depenalisation of homosexuality in Great Britain) was followed by a rise of social and political organisations from the 1960s onwards. This new movement that started in London, called the Gay Liberation Front, determined the future of the homosexual community in a significant way (Buckle, 5).

The Gay Liberation Front presented a challenge to the stereotypes that were imposed on homosexuals. Weeks explains the nature of the gay stereotype using a 1963 article called “How to spot a Homo” from the Sunday Pictorial:

“[the article] seemed to suggest that all homosexuals wore sports jackets, smoked pipes and wore suède shoes…the media reinforced the moral consensus by caricaturing its sexual deviants. They were either corrupters – usually of youth – or carriers of contagion dangerously poisoning society […]” (Weeks, 163)

Homosexuals were rejected, and often underwent a violent treatment at the hands of society; the violence could be both physical and mental in nature. Moreover, homosexuality was categorised as a ‘disease’ in the World Health Organisation’s catalogue of diseases until 1991. The Gay Liberation Front therefore aimed at changing the situation of the community at the grassroot level to counter these forms of violence which were often not evidently visible in society. Gay Liberation Front slogans such as “Gay is good” show the need for acceptance felt by the gay community at this time. In order to normalise homosexual socialisation, Gay Liberation Front organised ‘gay days’ to “provide space for men and women” who could be themselves “in a public setting” (Buckle, 80).

The demands of the Gay Liberation Front included the right of gay individuals to be themselves, that is the right to ‘come out’ in one’s social as well as professional circle. This meant freedom from the idea of a ‘double life’ according to which homosexuals had to pretend to be heterosexual in their public life, and their sexuality was a strictly clandestine affair. The Gay Liberation Front attacked the very idea of a heterosexual family and saw it as the root cause of the oppression of women, children and homosexuals, as is visible in an extract from their manifesto:

“The oppression of gay people starts in the most basic unit of society, the family, consisting of the man in charge, a slave as his wife, and their children on whom they force themselves as the ideal models. The very form of the family works against homosexuality.” (cited in Weeks, 196)

The Gay Liberation Front thus brought together the oppression of women and that of homosexuals, linking the two to sexism and showing that the common enemy of the two groups was patriarchy (Weeks, 197). Besides, Weeks interprets the emergence of the Gay Liberation Front in the following manner:

“The gay liberation movement was itself a product of the breakdown of the rigid taboos about sex which had blighted lives for generations, but it went further to question not only modes of sexual behaviour but rigid gender divisions themselves.” (Weeks, 7)

The Gay Liberation Front therefore represented the interests of not just homosexual men and women, but the entire queer community. The idea of a fluidity of gender and sexual roles was put forward as an aim of the movement, as against the heteronormative world of patriarchy. By doing so, the very notion of gender binarism was challenged along with the fixed societal roles that each person is expected to play in accordance with their gender. This was another point of overlap between the Gay Liberation Front and the Feminist movement.

2.3 Representation in the British Press and Cinema

“…as much as politicians would like to believe the power of their own influence, the media has provided a hugely influential forum in which ideas, attitudes, and perceptions of homosexuality have developed.” (Buckle, 9)

Just like the Gay Liberation Front, the British press and cinema too had a role to play in the social and political situation of gay individuals at that time. In this section, the emergence of a gay press will be discussed, before moving on to the role that British media and cinema played in the perception of homosexuality, especially during the AIDS crisis of the 1980s in the country.

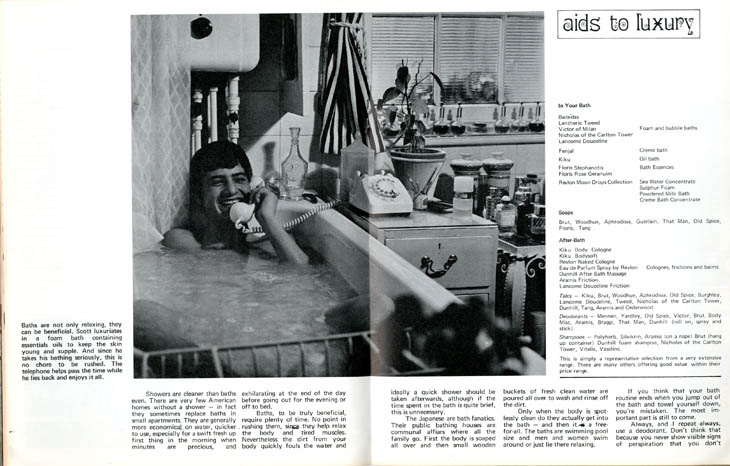

Following the Sexual Offences Act that legalised gay sex in private, from 1967 onwards, a series of gay magazines began to be printed. Magazines such as Spartacus wanted to attract readers, and at the same time define them. To achieve this, their content included lifestyle articles, fashion, stories of homosexual experience and so on (Buckle, 44). Another pioneer magazine in this period was Jeremy (Buckle, 41) which, along with other magazines of the time, used the word ‘gay’ interchangeably with the word ‘homosexual’, which shows that the readers of the magazine were aware of the American term by now. This marks the influence of the cross-Atlantic discourse on the British gay politics and culture. It is also a demonstration of a clear coming together of homosexuals as a community, identifying themselves as a group on the basis of their sexuality, both nationally and internationally (Buckle, 42). What was to follow were the events of the 1969 Stonewall riots in New York, which brought the homosexual community in the Western world to work as one unit, giving rise to a homosexual subculture with political activity spread across continents in the 1970s.

|

Jeremy - The Magazine For Modern Young Men No. 1, Volume 1 (London: Jeremy Publications, April 1969).

Source: Beatbooks.com

|

Spartacus - International Gay Guide, 1983

Source: houstonlgbthistory.org

|

Homosexuality had a complicated relationship with mainstream media and newspapers, as the British media remained reticent on the subject. It was only in the 1950s that newspapers decided to end “their self-censored relationship with homosexuality” (Buckle, 46), because prior to this, they preferred not to bring up debates or news about this ‘social problem’. In 1952, The Sunday Pictorial published a series of articles called ‘Evil Men’, taking a clear stand against any future legislation that could one day legalise homosexuality, as there were talks of introducing one at that time. One of their articles sheds light on the perception of homosexuality in British society at that time:

“[…] the chief danger of the perverts is the corrupting influence they have on youth. Most people know there are such things – ‘pansies’ – mincing, effeminate young men who call themselves queers. But simple decent folk regard them as freaks and rarities. […] If homosexuality were tolerated here, Britain would rapidly become decadent” (Sanderson, cited from Buckle, 46).

Not only was the general public influenced by the negative tone of the newspapers, homosexuality began to be defined and understood in these terms by everyone, including homosexuals themselves (Buckle, 47). There were constant associations between homosexuality and paedophilia at this point in time; the public opinion remained largely negative in the 1950s, and continued even until much later (Buckle, 48). But what was clearly established were the polarities between homosexuality and heterosexuality; homosexuality that was once seen as a temporary aberration became a distinct sexual identity in the 20th century with its own characteristics, its own language and its own culture, however peripheral it may be.

By the 1970s, the situation improved a little. The newspapers began to be more open on the subject of homosexuality. However, there was still an explanatory tone adopted on the homosexual subject to facilitate the understanding; the terms related to gay culture were often defined and redefined in articles. This sheds light on the fact that the gay movement was at a nascent stage, and there was a major lack of awareness of the general public on the matter (Buckle, 49).

This period also saw the rise of cinema with homosexual protagonists. According to Sebastian Buckle, Victim (1961) was a pioneer film on the topic of male homosexuality. This film, followed by many others, confirmed the commitment of British cinema to bring forth the subject of homosexuality for public consumption. Of course, this did not necessarily entail a change in public opinion. While the presence of homosexual characters guaranteed visibility to the community, the lives of these characters often revolved around the themes of loneliness and unhappiness (Buckle, 65).

Two contrasting depictions of homosexuality thus emerge in the 1970s. Buckle feels indeed that British society produced extremely oppositional public images of homosexuality: on the one hand, British journalism took a conservative approach on the subject, and on the other hand, films and television productions challenged the stereotypes of homosexual individuals in the public imagination (Buckle, 120). Cinema and television moved away from the sad and pitiable representation of homosexual characters, accepting to show portrayals closer to real life.

The role of the press (both gay and mainstream) changed in the 1980s with the AIDS crisis. While the gay press challenged the government for their neglect of the homosexual population, the mainstream newspapers were quick to link homosexuality and AIDS based on the fact that the disease seemed to have appeared in homosexual men when it was first recorded. It was conveniently named ‘the gay plague’ by the British press. Therefore, the tone of the mainstream newspapers on this subject remained negative, which in turn produced a negative public image of homosexuality. Newspapers such as The Daily Telegraph called it “a supernatural gesture by a disapproving almighty” (Buckle, 130), thereby declaring that AIDS was in fact a punishment for the ‘unnatural acts’ carried out by homosexual men. The reproach did not stop here, homosexuality was in fact blamed for the origin and the spread of the illness (Buckle, 131), and the homosexual population began to be seen as a threat to the heterosexual population. Frank Pearce brings forth the idea that newspapers influenced their readers to pass moral judgement on homosexual individuals: the press covering was rarely ever neutral. In addition to this, there was a legal move to discourage and eventually ban the teaching of homosexuality in schools Section 28 under the Local Government Act 1988. The press manifested clear homophobic tendencies when talking of the AIDS crisis and the ‘promotion of homosexuality’ in schools (as cited in Buckle, 144).

3. The Contemporary Period

In this section, the perception of homosexuality in 21st century Great Britain will be discussed, together with the measures taken to improve the social and political situation of queer individuals. Certain clashes within the queer movement will also be briefly discussed.

Even as late as the beginning of the 21st century, homosexuality did not pass for a “legitimate public culture” in the UK (Mills, 254) because of Section 28 that prohibited the ‘publicity’ of homosexuality in the public domain. As a direct consequence to this, organisations like art galleries, libraries and museums distanced themselves from events organised for the sensibilisation of the queer cause. Section 28 was later repealed in 2003 and consequently abolished.

There was clearly a lot of work to be done in terms of civil rights for gay people in the 21st century, now that the struggle for decriminalisation was over. It was now time to bridge the remaining gap between the rights of homosexual and heterosexual people. To trace briefly the achievements of the last century, after the 1967 law decriminalising gay sex, the wait for progress was quite long. Following an appeal in 1994, the age of consent for homosexual relationships was lowered from 21 to 18; one of the eventual outcomes of this proposition was the Civil Partnership Act of 2004. Under this act, same-sex relationships acquired the same legal standing as heterosexual marriages. Another law that gave homosexual individuals legitimacy in society was the Sexual Orientation Regulations in 2006, under which discrimination against people on the basis of their sexual orientation was banned.

British organisations such as Stonewall (named after the famous Stonewall riots in New York in 1969) worked towards the overall empowerment of homosexuals. In his book The Way Out, Sebastian Buckle mentions an interview with Ben Summerkill ((Ben Summerkill was Chief executive of Stonewall Equality Limited in 2013-2014. Founded in 1989, it was named after the 1969 Stonewall riots in New York City and aims to bring equality to gay, lesbian, bisexual and transgender people at home, at school, and at work.)), in which he noted that while some were fighting to have the legalisation of gay marriage in the UK, Stonewall was “doing the hard work of getting a quarter of a billion pounds out of Gordon Brown [the then Prime Minister of the UK] to fund public sector pensions for gay people” (Buckle, 186). Although different queer activists and organisations had diverse goals by then, due to the spreading out of the movement, the cause had achieved considerable visibility and steps were being taken to voice the concerns of the community.

Another step taken in order to provide legitimacy to queer identity was the creation of LGBT history month. It was introduced in the UK in 1987 and it is celebrated in February every year. Although it was at the turn of the century that the LGBT history month started to be celebrated, it gained more and more recognition and has recently encouraged various public and non-profit organisations to take part.

One of the contemporary trends in queer discourse is to attribute a homosexual identity to historical personalities. Mills cites a few in his article: “Lord Mountbatten, Florence Nightingale, Lawrence of Arabia, Catherine Cookson, Winston Churchill and William Shakespeare” (Mills, 253). This type of exercise has often been the focus of the LGBT history month festivities.

Of course, as in all social and political movements, problems within the community began to surface at this time. Mills rightly points to this situation by making reference to the popularly used acronym for the community: “T in 'LGBT' is often a fake T” (Mills, 256). Transgender individuals, as well as other minorities that do not even figure in the acronym, challenged the domination of discourse by the gay and lesbian experience. As a response to this demand, LGBT community became LGBTQIA, QIA standing for queer, intersex and asexual; however the acronym remained controversial (Jagose). For this reason, nowadays, the term ‘queer’ is sometimes used instead of LGBT(QIA) to designate all individuals that experience sexuality and gender in a different way from heterosexual individuals. Mills explains the importance of inclusion in the following way:

“While the accomplishments of gay identity politics are an important part of that history, part should not stand for whole. Queer histories should also be alert to the role of queer identifications and desires of all kinds in the daily life of the city.” (Mills, 259)

On the one hand, differences could be taken as a dilution of the cause; on the other, the situation could indicate the normalisation of the queer cause as many voices would guarantee that the cause move forward in terms of rights for queer people. A proof of this could be in the fact that the mainstream press showed a growing interest in the legal battles that were being won little by little by the community (Buckle, 211).

Conclusion

“[…] to be a homosexual in our society is to be constantly aware that one bears a stigma”. (Dennis Altman, cited in Weeks, 1)

The perception of homosexuality in the UK has been affected by religious, social, legal and medical persecution. The framework of punishment (or cure) evolved over time, but what remained constant was the homosexual experience. Homosexual identity was always accompanied by a fear of punishment, or later a fear of rejection in society. Writers such as E.M. Forster could not publish homosexual novels like Maurice in their lifetime for fear of being persecuted.

Homosexual subculture began to come into existence as early as the 18th century with ‘molly houses’ providing a social contact between individuals with the same sexual desires, which were later replaced by gay bars and other such institutions. British film and media had an integral part to play in spreading the homosexual cause as well as defining how the rest of the world perceived the community. Various organisations and political movements led to changes in law regarding the queer population, which helped pave the way for a more egalitarian society for the community.

In 2014, the Gay marriage legislation was passed in England, Wales and Scotland allowing same-sex marriages. However, there is still work to be done in the field: Northern Ireland does not allow same-sex marriages, and the Civil Partnership Act of 2004 is the only recourse for homosexual couples to get a legal recognition of their relationship.

Notes

Bibliography

BRAY, Alan. 1982. Homosexuality in Renaissance England. London : Gay Men's Press.

BUCKLE, Sebastian. 2015. The Way Out: A History of Homosexuality in Modern Britain, New York : I.B. Tauris & Co. Ltd.

DAVID, Hugh. 1997. On Queer Street: A Social History of British Homosexuality 1895-1995. London : Harper Collins.

ECO, Umberto. 2007. Histoire de la laideur. Paris : Flammarion.

FADERMAN, Lilian. 1981. Surpassing the Love of Men: Romantic Friendship and Love Between Women from the Renaissance to the Present. New York : Harper.

FOUCAULT, Michel. 1978. History of Sexuality Volume 1: An Introduction. New York : Pantheon Books.

FREEMAN. Elizabeth. 2007. GLQ Introduction volume 13, n°2-3.

GROSCLAUDE, Jérôme. 2014. « From Bugger to Homosexual: The English Sodomite as Criminally Deviant (1533-1967) », Revue française de civilisation britannique, CRECIB - Centre de recherche et d’études en civilisation britannique, volume 9, n°1, pp. 31-46.

HAGGERTY, George. 2000. Encyclopaedia of Gay Histories and Cultures Volume 2. New York : Garland Publishing Inc.

JAGOSE, Annamarie. 1996. Queer Theory: An Introduction. Melbourne : Melbourne University Press.

KAHEY, Regina. 1976. « A Good Gay History Bursts Out of the Closet ». Village Voice, 6 December, p. 94.

LYTTLETON, Edward. 1887. The Causes and Prevention of Immorality in Schools. London : Spottiswoode and Company.

McINTOSH, Mary. 1968. « The Homosexual Role », Social Problems, volume 16, n°2, pp. 182-192.

MILLS, Robert. 2006. « Queer Is Here? Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Histories and Public Culture », History Workshop Journal, n°62. pp. 253-263.

ROEN, Paul. 1994. High Camp: A Gay Guide to Camp and Cult Films Vol. 1. San Francisco : Leyland Publications.

RUST, Paula C. 1993. « ‘Coming Out’ in the Age of Social Constructionism: Sexual Identity Formation among Lesbian and Bisexual Women », Gender and Society, volume 7, n°1, pp. 50–77.

SANDERSON, Terry. 1995. Mediawatch: The Treatment of Male and Female Homosexuality in the British Media. London : Cassell.

SONTAG, Susan. 1964. Notes on Camp. Accessed on the 10th of May 2019 at <https://monoskop.org/images/5/59/Sontag_Susan_1964_Notes_on_Camp.pdf>.

TAMAGNE, Florence. 2006. A History of Homosexuality in Europe: Berlin, London, Paris 1919-1939, Volume II. New York : Algora Publishing.

WATERS, Chris. 2012. « The Homosexual as a Social Being in Britain, 1945—1968 », Journal of British Studies, volume 51, n°3, pp. 685-710.

WEEKS, Jeffrey. 1977. Coming Out: Homosexual Politics in Britain from the Nineteenth Century to the Present. London : Quartet Books.

Local Government Act 1988 (c. 9), section 28. Accessed on the 8th of May 2019 at <opsi.gov.uk>.

Appendix

Glossary

| Assimilation Politics | The politics followed by the early twentieth century organisations working for the homosexual cause, which aimed at proving that homosexuals did not pose any danger to society and could be integrated. |

|---|---|

| Buggery Law | Passed in 1533 in England, a law that condemned ‘unnatural’ sex acts. Punishment included a small fine and a few hours in the pillory. |

| Camp | An aesthetic style where what is considered usually bad in taste is considered beautiful. This style is often associated with the homosexual liberation movement. |

| Gay Liberation | A movement that emerged in the 1960s; as opposed to assimilation politics, this movement stands for the period where the community begins to be more assertive about their difference from the heterosexual norm. |

| Genderqueer / Gender Fluidity | The concept of rejecting gender binaries i.e. the existence of only male and female as the two genders. Genderqueer people experience the instability of gender identity and therefore do not accept being categorised as either male or female. |

| Homophobia | The fear and/or hatred of homosexual people that could manifest in forms of verbal or physical violence. |

| Lesbian Feminism | Called the ‘lavender menace’ in the 1960s, a movement that marked their difference from both the feminist and the gay movement (as lesbians faced suppression in both). |

| LGBT History Month |

https://lgbthistorymonth.org.uk/ Celebrated in the month of October internationally, and in February in the UK (since 2005). The aim is to provide queer role models and to increase visibility of the community. The celebration usually involves organising events in partnerships with museums and other organisations. |

| Molly Houses | A term used in the 18th century England to designate a place where homosexual men could socialise. At that time, such places/institutions were often equated with brothels in legal proceedings. |

| Pansy | A derogatory term for homosexuals, that both common people and the media used freely. |

| Queer | An umbrella term to take into account all non-heterosexual, non-normative identities. The word ‘queer’ is preferred over the use of LGBT to designate sexual minorities, as it is considered politically correct. |

| Section 28, Local Government Act 1988 | Under this clause, a local authority could “not intentionally promote homosexuality or publish material with the intention of promoting homosexuality" or "promote the teaching in any maintained school of the acceptability of homosexuality as a pretended family relationship". |

| Stonewall Riots | 28th June to 1st July 1969, New York. A series of violent confrontations between the police and the gay community. An event considered to mark the transition from assimilation politics to assertion of homosexual identity and the emergence of a sentiment of queer community. |

| Subculture | A group of people that distinguishes itself from the mainstream normative culture by developing their own vocabulary, values and belief systems. Homosexual subculture is the largest sexual subculture of the twentieth century. |

| The Homophile Movement | A movement in the early 20th century involving organisations challenging medical, legal, religious, economic institutions as well as the media to counter discrimination against homosexuals. The idea was to prove that homosexuals are just like heterosexuals and do not pose a danger to society. |

A Brief Timeline

| 1533 | Buggery law* |

|---|---|

| 1534 | Henry VIII’s breaking of ties with (Catholic) Rome |

| 1534-1641 | Only 3 people sentenced under the Buggery Law |

| From 1690s | Creation of Societies for the Reformation of Manners, religious societies etc. which aimed at prosecuting prostitutes, buggers and all that was considered moral indecency. Activities included raiding molly houses. |

| 1692-1725 | 90,000 arrests by the London Society under the Buggery Law |

| 1837 | Practice of pillory abolished |

| 1857 | Obscene Publications Act. Right to legally cease and destroy all obscene material that was for sale by the court of law. |

| 1861 | Offences against the Person Act replaced Buggery Law and sodomy became punishable with 10 years or life imprisonment. |

| 1885 | Labouchère Amendment: penalisation of act of ‘gross indecency’ (that is to say homosexual sex acts) between two male individuals. |

| 1890s | Havelock Ellis popularised the word ‘homosexual’ in English |

| 1890s | Oscar Wilde tried for being involved in sexual acts with men |

| 1913 | Creation of the British Society for the Study of Sex Psychology, to counter legal discrimination against homosexuals and to change public view of homosexuality in the UK |

| 1928 | Radcliffe Hall’s Well of Loneliness published. It was prosecuted under the Obscene Publications Act for lesbian content |

| 1957 | The Report of the Departmental Committee on Homosexual Offences and Prostitution (Wolfenden report) was published, which asked for the legalisation of homosexuality in the UK |

| 1967 |

Sexual Offences Act: decriminalised homosexual acts in private between male individuals. This law only extended to England and Wales |

| 1st July 1972 | First Gay Pride March, London |

| 1980 | Criminal Justice Act: decriminalised homosexual acts in Scotland |

| 1981 | Homosexual Offences Order: decriminalised homosexual acts in Northern Ireland |

| 1980s | AIDS crisis |

| 1982 | Acquired Immuno-Deficiency Syndrome used as a term for the first time |

| 1988 | Section 28 under the Local Government Act 1988 was introduced |

| 1994 | Age of gay sexual consent changed from 21 to 18 |

| 2004 | Civil Partnership Act passed, legitimising same-sex relationships |

| 2014 | Gay marriage legislation in England, Wales and Scotland. Northern Ireland does not allow same-sex marriages as of now |

*Homosexuality was never a punishable offence in the UK, as opposed to sodomy (anal penetration)

Pour citer cette ressource :

Nishtha Sharma, The Perception of Male Homosexuality in Great Britain from the 19th century to the Present, La Clé des Langues [en ligne], Lyon, ENS de LYON/DGESCO (ISSN 2107-7029), janvier 2020. Consulté le 27/01/2026. URL: https://cle.ens-lyon.fr/anglais/civilisation/domaine-britannique/the-perception-of-male-homosexuality-in-great-britain-from-the-19th-century-to-the-present

Activer le mode zen

Activer le mode zen