French Toast, Fatherhood and Fallibility in «Kramer vs Kramer» (1979)

Article réalisé dans le cadre du diplôme de l'ENS.

Introduction

In her essay The End of Love, A Sociology of Negative Relations (2021), sociologist Eva Illouz remarks that despite its fascination for love, our culture is rather silent about the “no-less-mysterious moment when […] we fall out of love.” She argues that the issue might be a question of narrative: “Perhaps our culture does not know how to represent or think about this because we live in and through stories and dramas, and ‘unloving’ is not a plot with a clear structure.” (3) Although Illouz is undoubtedly right, there are notable exceptions to this silence. A number of narrative works depict this event of unloving or end-of-love, particularly in American popular culture.

Divorce movies constitute a singular cinematic genre which comprises several subcategories. One of them consists in presenting the narrative from children’s perspective, as in Noah Baumbach’s semi-autobiographic movie The Squid and the Whale (2005). On the other hand, Robert Benton’s 1979 five Oscar-award winner Kramer vs Kramer belongs to the subgenre of films about divorce from the parents’ perspective, dealing with the question of child custody and the portrayal of fatherhood. It is based on the book of the same title published two years earlier by Avery Corman, which started to open up the debate on fathers’ rights. Noah Baumbach’s Marriage Story, released forty years later, is another great success of the genre. The two films follow a similar plot, where the separation is caused by the wife’s dissatisfaction and feeling of having been consumed by her marriage. Both the Kramers in Benton’s film and the Barbers in Baumbach’s fight for the custody of their son between New York and California. While Kramer vs Kramer leaves Joanna’s story on the side, Marriage Story follows Nicole’s new life in Los Angeles. The representation of therapy and of the couples’ legal journey testifies to the four decades that separate both works and shows taboos gradually breaking. In 2019 in Marriage Story, Nicole Barber’s lawyer Nora Fanshaw (Laura Dern) nevertheless reminds the audience of the persisting gender imbalance:

We can accept an imperfect Dad. Let’s face it, the idea of a good father was only invented like thirty years ago. Before that fathers were expected to be silent and absent and unreliable and selfish and we can all say that we want them to be different but on some basic level we accept them, we love them for their fallibilities. But people absolutely don’t accept those same failings in mothers. (emphasis written in Baumbach’s script)

Kramer vs Kramer came out at the turning point mentioned in this passage, when it became possible to present the idea of a good father and, even, of the father being the better parent. How can a movie bring such a shift in perspective, and how did Benton’s movie portray the making of a father figure? Based on Benton’s film, this article will first provide contextual information on divorce, fatherhood, and fallibilities before exploring the place of male heroism in intimate spheres and examining the gradual eviction of women that often comes with it. It will finally propose an analysis of the breakfast scenes at the beginning and the end of the film, built as a diptych.

1. Divorce and Hollywood

Divorce and end-of-love stories drift away from the image of the perfect romance. They hint at the idea that fairy tale stories can end and that another story could start where they end. Showing the intimacy of couples who used to be in love and now struggle with what remains complexifies gender norms: individuals have to reinvent themselves outside of family norms and gender roles, especially when a child is concerned. At the same time, this allows for new representations to break away from traditional stereotypes.

The popularity of such family dramas in Hollywood can be linked to the legalization of the no-fault divorce by the then governor of California Ronald Reagan in 1969, which was progressively adopted across the whole country. Between 1960 and 1980, the divorce rate in the US more than doubled, largely due to this revolution of not being required to prove one party’s wrongdoing to dissolve the marital contract. This brought a huge change in mentalities, while divorce allowed more and more women to gain autonomy.

In Benton’s film Kramer vs Kramer, the Kramer household may look idyllic on paper, but the opening scene shows Joanna Kramer (Meryl Streep) trapped in her social and family straitjacket. She is no longer satisfied with her yuppie daily life with a man she spends her life waiting for, Ted Kramer (Dustin Hoffman). The movie starts with her departure to finally take control of her life, and it is up to her husband to take charge of their son and the story, since it is his day-to-day life that we will be following. Joanna ends up finding in her independence a professional aspiration, which in the American discourse of that time takes the form of earning more than her husband for whom she had interrupted her career, at the cost of her role as a mother. The movie’s particularity lies in the progressive relegation of Ted Kramer to a domestic sphere, celebrating a father’s newfound role as a parent.

Kramer vs Kramer made a lasting impression, showing, perhaps for the first time in Hollywood, an image of fatherhood under construction, caring and fragile. The New York Times commented on its release that:

In a country where the lives of one million children are changed each year by divorce, the movie makers could hardly have picked a more provocative theme. The plot of the film, one that would have sounded bizarre a decade ago, seems entirely plausible in today’s world of mothers seeking self-fulfillment and fathers seeking custody of young children. (Dullea, 1979)

The fictional Kramer family case even became emblematic of men’s right to custody of their children. A recent article in USA Today magazine analyzes this turning point in these terms:

Men were becoming thinkers and feelers, not just doers. Fragile and emotional. Getting in touch with their feelings, as it was known at the time. Especially onscreen: Overachiever Ted Kramer is seen unmoored by the simple task of making French toast for his son. His single-father fear and sadness are on wide-screen display.

“Kramer vs. Kramer” was, in fact, one of no fewer than six big-name movies released in the final three months of 1979 that showcased this evolving American male. “Starting Over” (with Burt Reynolds), “10” (Dudley Moore), “And Justice for All” (Al Pacino), “The Electric Horseman” (Robert Redford) and “Chapter Two” (James Caan) each presented portraits of successful career men at mid-life, wrestling with emotional issues. (McKairnes, 2019)

These films were the topic of many magazine articles, testifying to the exemplary ability of Hollywood to paint and perhaps even reshape the social norms of the time. In the 1970s, aligning with the second wave of feminism, more and more male roles exposed some form of male vulnerability on screen, which in turn influenced our imagination.

2. Beautiful Loser: Fatherhood Fallibility, Masculinity and Heroism

In Benton’s film, Ted Kramer is presented as vulnerable when his status as husband turns into that of ex-husband. He embodies a character who, at first glance, seems ordinary, in situations that are also ordinary. This normality accompanies his family life, with a young child to raise. In this context, his house — progressively emptying from signs of his wife — becomes the main environment, alongside the park, the street, and the court for the legal aspects.

Within this ordinariness however, a small accident in the playground turns the father into a heroic figure running through Manhattan in a tracking shot that follows Ted with his child bleeding in his arms. In another scene, a mere tantrum becomes a significant event that requires a resolution. Kramer, in this portrayal of a struggling man who suddenly finds himself having to take on the role of full-time father, is somehow saved by the difficulties he faces: gradually, we see him become more and more expressive, fulfilled and attentive to life’s tiny details thanks to his son Billy. Like a modern-day hero, he wins the spectators’ empathy as he shows his love for his son.

Stella Bruzzi, Professor of Film Studies at the University of London, argues that Kramer vs Kramer is undoubtedly the most influential and important cinematic representation of the father figure. In her book Bringing Up Daddy: Fatherhood and Masculinity in Post-war Hollywood (2005), she argues that this film more than any other asserts the supremacy of the liberating model of fatherhood for the middle class. Bruzzi states that the character of Kramer crystallizes the desire to revive belief in masculinity and patriarchy as well as the rejection of traditional masculinity, in that it proposes an alternative model of fatherhood. This is what makes the richness of such a film.

However, Hollywood generates a whole economy based on the principles at the heart of the American mentality, and the representations it offers reflect the ideal American society more than they upset it. In her analysis of the film, Bruzzi notes that even films that criticize traditional father figures emphasize the father’s importance as a role model. Ted Kramer indeed rises from the role of the absent father and workaholic husband to that of the perfect father, putting his child before work (he is fired because of it and accepts a lower paying job and a downgrade in the hope of gaining custody of his son), before his social and romantic life (he only has one short affair and mostly cultivates his one friendship with Joanna’s old friend who is divorced and does not really see Ted without his child) and learning how to educate, be patient and attentive to a small kid. This point is essential: the alternative model of masculinity proposed by Robert Benton’s film is optimistic.

3. Better than a Mother?

The film simultaneously registers the gradual eviction of the mother figure, which Meryl Streep’s acting — who accepted the role of Joanna on condition that she would rewrite some parts of it, an initiative encouraged by Benton (Holleran, 2019) — attempts to balance out. Thanks to cinematographer Nestor Almendros’ direction, the once-removed mother’s presence comes back as a still image in the frames containing her black-and-white photograph, a beautiful but harmless woman who is tucked away in boxes or brought out again when her image is deemed reassuring. Indeed, Joanna’s portrait that her husband puts away in a box, along with anything that might remind us of her existence and hence her departure, is snatched up by Billy, before Ted discovers it and puts it on display on his son’s bedside table, therefore setting his ego aside.

Joanna nevertheless remains at a distance. For instance, she is seen from behind the glass of the café through which she watches her son enter school for months, conjuring up the idea of distance and coldness. Conversely, Ted is always active and on the move, running to the hospital through the streets of New York when his son has an accident, hailing cabs, cooking or cutting his son’s steak while reading his newspaper. He is constantly associated with materiality and with his son’s physical being.

Ted’s presence is highlighted by the repetition of everyday acts, such as the morning scenes in which we hear him urinating after Billy had used the bathroom, a reminder of a symbiosis in a masculine routine that Joanna could never share. The first scene in the bathroom features a glimpse of Joanna’s photo in the bottom right-hand corner of the screen, before it is replaced by a photo of Billy in later shots of the corridor. The family recomposes itself and learns to do without the mother. When Billy undergoes surgery, his father’s face is so close that he gives the impression that the thread stitching his son’s cheek is brushing against him, symbolically linking them all the more.

Joanna ceases to represent a physical maternal presence to her son from the first few seconds of the film. Her departure makes her side of the narrative dependent on her husband’s words and his side of the story. Thus, when she writes a letter, Billy and the audience hear it through Ted’s flinching voice. When she feels ready to confront her husband, she comes with a prepared speech that leaves Ted vulnerable and impulsive, and he throws a glass at the wall as a response. However, this gesture seems to expose his fallibilities as a positive thing: subjects regarding his son make him react in a very emotional “manly” way, thus giving emphasis to his love for him.

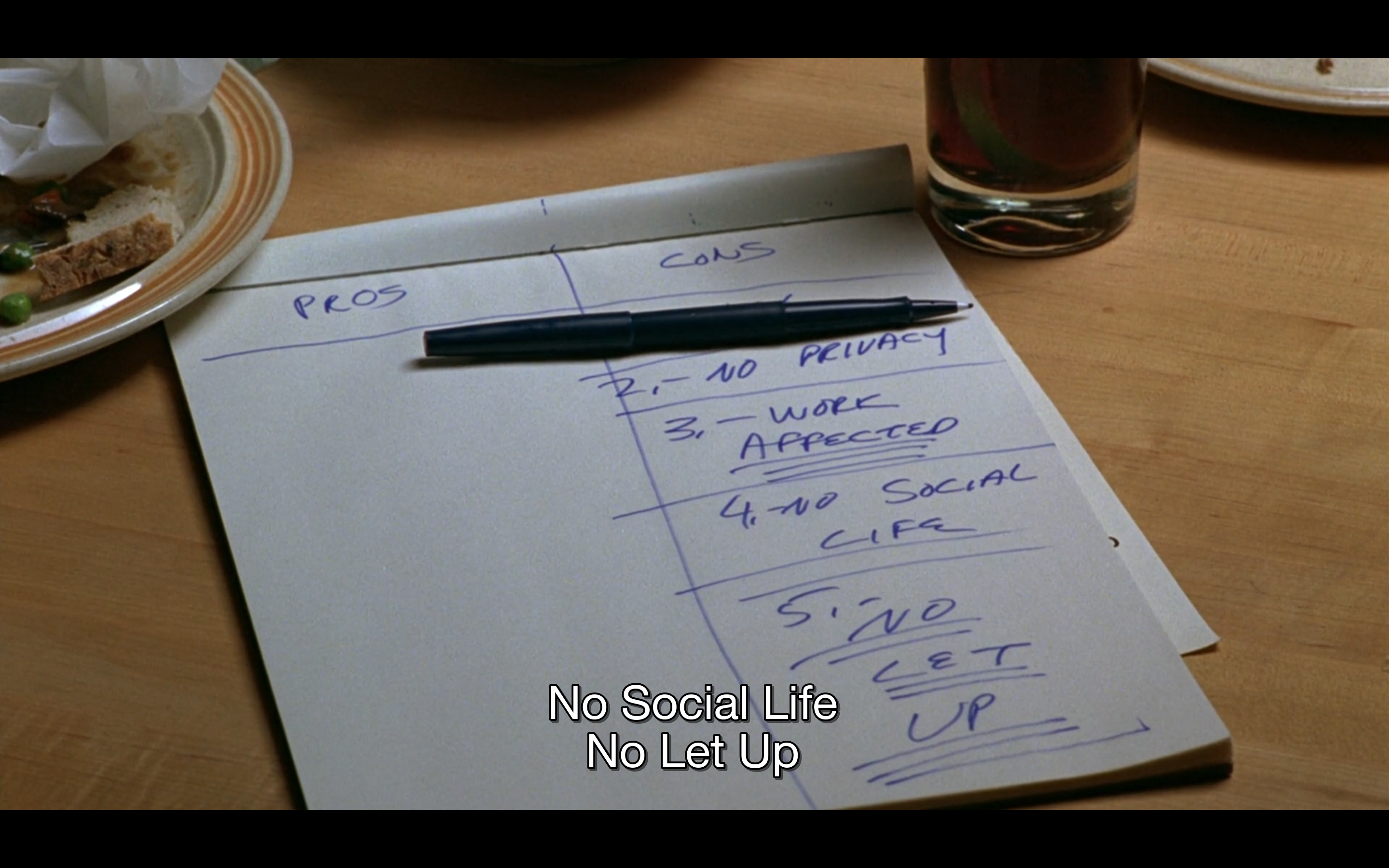

In court, Joanna defends herself with emotionally charged words uttered as her tears flow while Ted defends himself with rhetorical weapons. He asks why, if a woman can have as much ambition as a man, his wife would necessarily be a better parent because of her gender. However, emotions also drive his case: when asked by his lawyer to write down the pros and cons of getting custody of Billy, Ted only comes up with cons. He nonetheless decides to fight for custody and thus for his role as a dad.

Conclusion

Kramer vs Kramer’s character of Ted gradually becomes the father par excellence. Through the power of scenes that speak for themselves, Ted wins the public’s sympathy, as evoked by their mutual friend Margaret. The latter probably best represents the perspective of viewers at the time: as a feminist, she encourages Joanna to emancipate herself while siding with Ted, whom she has gradually seen become a better parent to Billy. She tells Joanna during the court hearing that the father and his son are beautiful together and if she saw them interact, there would be no lawsuit. The movie’s happy ending is thus unsurprisingly showing Joanna side with the audience and Margaret, despite having won the custody battle: in the final scene, she comes to take her son home, before recognizing that he is already home with his father and thus acknowledging the transformation of a self-obsessed man into a great father.

The film’s image of fatherhood is based on this subtle transfiguration. Ted fails to fit the traditional male role as a husband unable to fulfill the needs of his wife who only thrives by being away from him. Single father Ted is also an incompetent worker, letting his family life encroach on his professional life to the point of losing his job and having to plead for a living far below what he should aspire to. Nevertheless, these failures are precisely what enable him to turn his story into a success story: they elevate him to the status of a good father, capable of sacrificing his time, money and even custody of his son until the last minute. In the end, these events make him a better parent.

Commented excerpt

Ted Kramer is initially presented as a disorganized man and his limited attention span is emphasized by the movie’s editing. In his first appearance, late at night in his boss’s office, Ted is interrupted while telling a story. He then tries to hail a cab to get home, but allows himself to be dragged down the street by his superior who wants to continue their conversation. These scenes are interspersed with shots of his wife packing her bags: she is seen waiting for him, and Ted’s sharp knock on their door startles her. Unconcerned with his wife’s state, Ted kisses her, starts telling her his news, and simultaneously calls someone on business matters. At the start of the film, Joanna is already practically a ghost in her husband’s eyes.

The morning after she leaves, a disheveled, clumsy Ted interacts with his five-year-old son but is unable to live up to his role as a father. The scene that follows can be read as the first part of a diptych that reveals the heart of the film, where the relationship between the present and absent characters is played out in the preparation of French toast for breakfast.

At the very beginning of the scene, still in the corridor, Ted attempts to explain to his son that there are disagreements in the marriage but fails to say more. The conversation then happens on a meta level about French toast and coffee, with Billy telling Ted that the coffee is going to be way too strong, allowing Ted to try to overcome his loss by stating that his wife made it too weak.

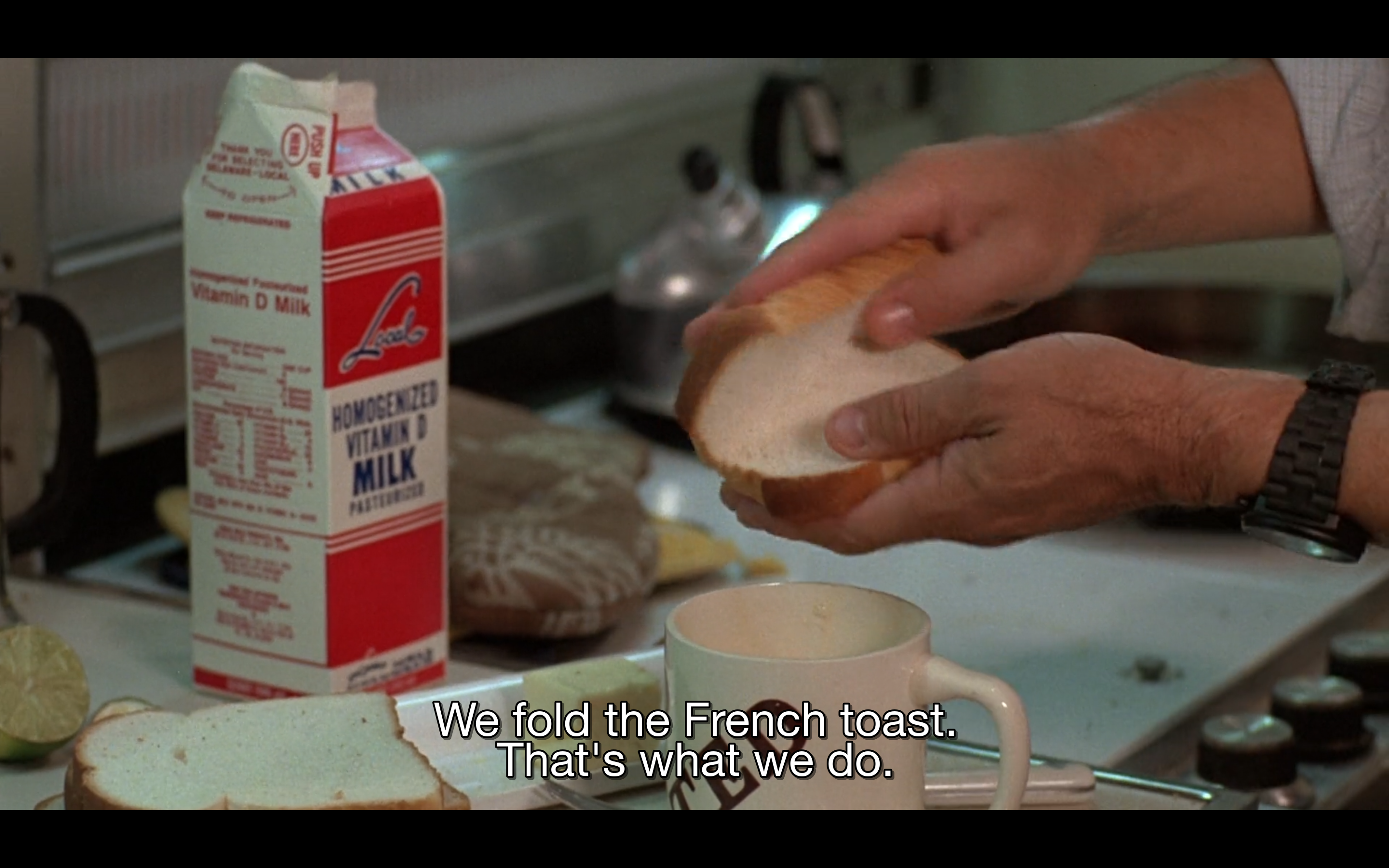

Ted wants to hold his head high in front of his son Billy, but his every move betrays his feverishness. As the adult in the kitchen, he feels forced to justify his actions, but his rhetoric is incoherent. He proudly points out that in restaurants, all the best chefs are men, and when eggshells are mixed in with the French toast, he asserts that this improves the dish by adding crunch. Ted then tries to fit the toast into a mug bearing his name, but the toast obviously does not fit all the way. When Ted realizes this, he tries to convince Billy that everything is calculated, that the bread must always be folded in half.

Billy’s complaints that he does not like the toast in pieces can be interpreted as his understanding of the whole situation: the child refuses his mother’s departure, symbolically represented in the breaking of the couple (or toast) in half, resulting in pieces. Ted tries to convince Billy that it is all the same, whole, folded, in pieces: “bread is bread,” and that “you get more bites that way!” This is the type of arguments divorced parents might try to give to their children, contending that there will be not one but two birthday celebrations, presents and holidays.

In this first attempt at a father-and-son breakfast, Ted is stereotypically masculine. When his son reminds him that he has forgotten the milk, he improvises with faked confidence. Ted Kramer is always right, especially when it comes to maintaining a veneer of paternal authority. When Ted finally burns himself with the hot frying pan, we can hear Dustin Hoffman’s changes to the script. The actor does not just exclaim “goddamn” as written in the scenario, but “goddamn her”. For Ted, wounded and lost in the wake of his wife’s departure, this is a case of men versus women.

The second part of the diptych takes place at the very end of the film, when Ted and his son spend their last breakfast together before the latter expects to go away to live with his mother. This time, Ted and Billy’s gestures are perfectly choreographed, highlighting their complicity.

The trifles of everyday life are given the highest value and each gesture of this silent breakfast routine is meaningful. Billy beats in the eggs in a large glass bowl and Ted adds in the milk. In the first breakfast scene, a mug with Ted’s name was previously used as a container: the change from mug to bowl could be seen as a symbol of Ted’s transformation, from an individual, self-centered, narrow, office object towards a broader, more humble, efficient and multifunctional bowl. Ted is no longer the center of his world, as the mug bearing his name might have suggested at the start of the film; instead, it is the function of a far more banal object, a simple Pyrex, that he chooses for his son’s sake.

The scene ends with a silent look from Billy towards his father, both smiling and tearing up. All the details that cinematographer Nestor Almendro dwells on present the audience with a new domestic portrait of the father-son relationship. The close-up shots include the viewers in an intimacy made stronger by the unusual sight of a man performing household tasks in the context of the 1970s. This is the birth of a father on screen, a view today’s audiences might too easily take for granted.

|

|

|

Figure 5: Billy and Ted share a silent look while making French toast

|

|

Bibliography

BAUMBACH, Noah, dir. 2019. Marriage Story.

BENTON, Robert, dir. 1979. Kramer vs Kramer.

BRUZZI, Stella. 2005. Bringing Up Daddy: Fatherhood and Masculinity in Post-War Hollywood. London: British Film Institute.

DULLEA, George. 1979. “‘Kramer vs Kramer’ Child Custody: Jurists Weigh Film vs. Life”, The New York Times, 21 December 1979, https://www.nytimes.com/1979/12/21/archives/child-custody-jurists-weigh-film-vs-life-fiction-and-fact.html.

HOLLERAN, Scott. 2019. Interview of Robert Benton. https://www.scottholleran.com/?s=interview+with+robert+benton.

ILLOUZ, Eva. 2021. The End of Love: A Sociology of Negative Relations. Cambridge: Polity Press.

McKAIRNES, Jim. 2019. “How ‘Kramer vs. Kramer’ Hit a National Nerve, 40 Years before ‘Marriage Story’,” USA Today, 19 December 2019, https://eu.usatoday.com/story/entertainment/movies/2019/12/19/kramer-vs-kramer-hit-national-nerve-40th-anniversary/2694519001/.

Pour citer cette ressource :

Elsa Benamouzig, French Toast, Fatherhood and Fallibility in Kramer vs Kramer (1979), La Clé des Langues [en ligne], Lyon, ENS de LYON/DGESCO (ISSN 2107-7029), novembre 2023. Consulté le 20/02/2026. URL: https://cle.ens-lyon.fr/anglais/arts/cinema/french-toast-fatherhood-and-fallibility-in-kramer-vs-kramer-1979

Activer le mode zen

Activer le mode zen