Beyond the Damsel in Distress: The Evolution of Female Representation in American Horror films

Introduction

Alfred Hitchcock once famously quipped, “Torture the women!” ((Hitchcock was talking to an interviewer about the finale of The Birds (1963): “I always believe in following the advice of the playwright Sardou,” Hitchcock remarked. “He said, ‘Torture the women!’ ... The trouble today is that we don’t torture women enough” (quoted in Spoto, 1983, 458).)), a remark dismissed at the time as dark humor, yet one that reveals a deeper, troubling pattern of misogyny embedded in the history of horror cinema. Though said decades after the genre’s early development, Hitchcock’s words reflect an enduring trope: the routine depiction of women as targets of violence and suffering. Horror films, as Noël Carroll defines them, are narratives designed to evoke fear, disgust, and dread through encounters with threatening, often unnatural forces that challenge everyday norms (The Philosophy of Horror, 1990). Crucially, the genre is rooted in transgression: it thrives on the violation of cultural taboos and the exposure of what society represses. As Robin Wood asserts, “the true subject of the horror genre is the struggle for recognition of all that our civilization represses or oppresses” (Wood, 1986). In this light, the victimization of women in horror is not incidental but foundational. Female characters are frequently subjected to suffering and punishment, their pain used to drive plot, evoke fear, or reinforce moral lessons, but also to captivate and unsettle its audience (Hankins, 2020).

Glenn G. Sparks and Cheri W. Sparks explored why violent films captivate audiences, suggesting that viewers derive a distinct and multifaceted pleasure from witnessing onscreen violence. Similarly, Rikki Schubart likens the experience of watching horror films to the enjoyment of “play-fighting” (Schubart, 2007). She argues that horror offers a safe space to confront disturbing or traumatic scenarios without facing real-world danger. Additionally, horror films may provide a form of catharsis, allowing viewers to release repressed fears, anxieties, or frustrations in a socially acceptable context. By confronting fictional threats, audiences can indirectly process real-world uncertainties and taboos. This emotional exercise can be both thrilling and therapeutic, offering a temporary escape while reinforcing a sense of personal resilience and control.

From its earliest incarnations, the horror genre has consistently positioned women at the center of fear, as primary victims upon whom terror is enacted. Classic films like The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (Robert Wiene, 1920) and Nosferatu (Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau, 1922) were instrumental in shaping the visual and thematic language of horror. These German Expressionist works, with their distorted sets, shadowy aesthetics, and psychological intensity, deeply influenced American horror cinema, particularly early Universal films such as Dracula (Tod Browning, Karl Freund, 1931) and Frankenstein (James Whale, 1931). These films helped establish a lasting narrative formula: women are depicted in states of vulnerability and fear, often serving as the main witnesses to the monstrous. Within these stories, female characters do more than simply endure terror, they become the emotional conduit for the audience. Their reactions, whether recoiling from the grotesque, succumbing to the eerie allure of the supernatural, or screaming in helplessness, shape the viewer’s own emotional experience. Their suffering functions both as spectacle and as a signal, emphasizing the horror and eliciting affective responses. In this way, the relationship between the masculine-coded monster and the female victim is not incidental but central, each defined and reinforced by the presence of the other, forming a foundational dynamic that underpins the structure and emotional power of the genre.

However, over time, this portrayal has evolved, and women have increasingly been depicted as active participants in their own fate, from the heroines who confront supernatural threats to the villains who embody the horror itself. This shift in representation not only reflects changes within the genre but also mirrors broader societal transformations regarding gender roles, power dynamics, and the evolving perception of women’s agency. Exploring these shifting portrayals provides insight into how horror reflects, challenges, and sometimes reinforces societal norms and fears surrounding women.

1. The Early Days of Horror (1920s-1960s): The Evolution of the Victim and Damsel in Distress Archetype under the Influence of the Hays Code

1.1 Women at the Heart of Early Cinema: Pioneers, Protagonists, and Power

The silent era of cinema, defined by its innovation in both storytelling and technique, flourished in the 1920s and early 1930s: filmmakers enjoyed a remarkable degree of creative freedom, particularly in their portrayal of women. Female characters in early horror films were not exclusively confined to passive or morally sanitized roles; they could be complex, commanding, and even dangerous. Women appeared as protagonists, antagonists, and femmes fatales, often wielding considerable influence over the male characters around them (Lewis, 2021). These characterizations reflected the central role women played in shaping early cinema: the film industry was a bold, experimental space that included, and often depended on, women’s voices both behind and in front of the camera. Pioneering filmmakers like Alice Guy-Blaché and Lois Weber broke ground as directors and screenwriters, while actresses such as Mary Pickford extended their impact beyond the screen, co-founding studios like United Artists and asserting creative control over their work. According to recent findings from the American Film Institute (Tangcay, 2023), women occupied a larger share of roles as writers, directors, and producers during the silent era than at any other point in the first century of American filmmaking. Between 1915 and 1925, screenwriters like Frances Marion and Anita Loos were responsible for writing nearly half of all silent films. At the same time, Lois Weber became the highest-paid director in the industry, male or female, leading some to describe the period as a “manless Eden”, a rare moment in film history when women’s creative authority was both visible and celebrated (Malone, 2023).

Horror films in particular offered a rare space for daring portrayals of women. Female characters were not relegated to passivity; instead, they often stood at the center of the narrative, sometimes as victims, but just as often as powerful, even monstrous figures. In The Cat and the Canary (Elliott Nugent, 1927), the female protagonist Annabelle West is portrayed as helpless, yet she also displays wit and resilience as she navigates a haunted mansion and uncovers the mystery. In Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (Victor Fleming, 1931), Ivy, a working-class woman, becomes both a victim and a symbol of transgressive female desire; her sexuality and vulnerability disturb the male moral order and ultimately lead to her demise. Similarly, Murders in the Rue Morgue (Robert Florey, 1932) presents women as central targets of scientific and sexual experimentation, reflecting deeper anxieties about female autonomy and embodiment. While these films were all directed, and primarily written by men, women did contribute behind the scenes to early horror. For example, Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1920) was co-written by Clara Beranger, a prominent female screenwriter of the silent era, and The Mummy (1932) originated from a story treatment by Nina Wilcox Putnam, whose concept helped define one of Universal’s iconic monsters. Earlier still, Alice Guy-Blaché, one of cinema’s first directors, explored gothic and suspense themes in works like The Ocean Waif (1916). These portrayals, of women as clever survivors, unsettling figures of desire, and subjects of male fear, were transgressive in that they disrupted traditional gender roles, challenged dominant moral frameworks, and reflected broader cultural tensions of the Roaring Twenties and early Depression era, a time of social transformation and evolving definitions of femininity.

1.2. The Damsel in Distress Trope

However, horror films at the time could also reinforce stereotypical representations of female characters. In The Phantom of the Opera (Lon Chaney, 1925), the female protagonist, Christine Daaé, is emblematic of how early horror films used the damsel trope to underline male dominance and female submission in both romantic and social hierarchies. While being ostensibly the object of both the Phantom’s obsession and Raoul’s affection, the female character lacks meaningful agency in the conflict that unfolds. Christine is abducted by the Phantom, a figure who both desires and controls her. Rather than confronting or resisting him directly, she is portrayed as fearful, submissive, and dependent on Raoul for rescue. The film thus constructs Christine as a passive prize over which two men struggle: her voice and beauty are central, but her will is not. Christine’s role as a damsel in distress reinforces the notion that women in horror exist to motivate male action, not to act themselves. Her value is rooted in vulnerability, which validates male heroism and sacrifice.

Dracula (Tod Browning, Karl Freund, 1931) holds a central place in the development of American horror cinema. Its influence is evident not only in its formal elements, such as the slow pacing, theatrical performances, and atmospheric lighting, but also in how it established narrative and ideological patterns that would persist in the genre. While it is often praised for Bela Lugosi’s performance and its role in popularizing the vampire on screen, the film’s gender politics merits closer scrutiny. Specifically, the portrayal of Mina Seward (Helen Chandler) reflects and reinforces a set of assumptions about women’s agency, morality, and vulnerability that limit her narrative function.

Mina is positioned as a passive figure, caught between Dracula’s coercive influence and the protective efforts of the male protagonists. Her transformation into a vampire is framed not as a choice but as a contamination, something that happens to her, necessitating rescue. The men around her, her fiancé Jonathan Harker, her father Dr. Seward, and Van Helsing, are not only more active agents in the plot but are also granted the authority to diagnose, manage, and ultimately resolve the threat that Dracula represents. Mina, by contrast, is largely excluded from these conversations and decisions, even though her body and mind are the sites on which the conflict plays out.

This dynamic reflects a broader pattern in early horror: the female character features as the symbolic ground for moral struggle, rather than a participant in it. The film offers no real opportunity for Mina to resist Dracula on her own terms. Even in scenes where she appears to express internal conflict, such as when she speaks of her attraction to Dracula’s power, these moments are quickly neutralized by the men’s interventions. Her recovery at the end of the film, marked by a return to her prior state, reinforces a conservative resolution, one in which the reassertion of normative gender roles is treated as a form of closure.

The film’s structure thus limits what can be understood as agency for its female characters. Mina’s importance is not tied to what she does but to what is done to her. The narrative treats her transformation less as an exploration of individual change and more as a problem to be solved by others. While Dracula helped define the visual and thematic contours of cinematic horror, it also codified a model in which women’s power is either suspect or erased altogether. Rather than challenging this model, the film ultimately affirms it.

1.3 The Hays Code (1934)

As the film industry grew more profitable in the late 1920s and into the 1930s, a combination of institutional consolidation and the enforcement of the Hays Code ushered in a new era, one increasingly dominated by men behind the scenes. Institutional consolidation refers to the growing dominance of a few major studios that centralized control over film production, distribution, and exhibition, effectively sidelining many independent voices, including women. While women continued to captivate audiences on screen, their creative authority behind the camera was systematically eroded. The narrative power they once held was gradually stripped away.

The implementation of the Production Code, also known as the Hays Code, in 1934 also marked a sharp turning point. Portrayals of women as sexually autonomous, morally complex, or transgressive were swiftly curtailed. Characters who had once embodied independence, rebellion, or danger were recast into sanitized, conservative archetypes: the virtuous wife, the innocent victim, the moral exemplar. The Code did more than censor content, it reshaped the industry’s storytelling power dynamics, narrowing the range of women’s representation on screen and reinforcing a male-dominated authorship of film narratives. The Hays Code explicitly promoted “correct standards of life”, emphasizing the sanctity of marriage and the home. As a result, women in films were largely confined to traditional roles as wives, mothers, and caretakers, with narratives that reinforced their duties to family and domesticity. Female ambitions that extended beyond these boundaries were often framed as misguided, dangerous, or disruptive to social order (Jeff and Simmons, 1990).

Under the Code’s influence, the “damsel in distress” trope gained prominence. While this archetype existed before the Code, it flourished during this era, portraying women as innocent and passive figures in need of male rescue. These characters were symbolic of purity and vulnerability, rather than strength or autonomy, and their value was often defined by their relationship to male protagonists. For example, in King Kong (Merian C. Cooper, 1933), Ann Darrow functions less as a character with interiority than as a figure whose helplessness justifies the violent spectacle around her.

Despite the Code’s limitations, some filmmakers found ways to subvert its restrictions. Through the use of subtext, allegory, and visual symbolism, they crafted more layered and nuanced portrayals of women, quietly challenging the dominant narrative. In Cat People (Jacques Tourneur, 1942), for instance, the protagonist Irena is a Serbian immigrant who believes that if she consummates her marriage, she will transform into a panther and kill her husband. This fear, rooted in folklore and inherited trauma, symbolizes her repressed sexuality and deep cultural alienation. Irena’s inability to reconcile her desire with societal expectations of femininity and domesticity isolates her emotionally and physically. Although her story ends in tragedy, the film uses metaphor, her transformation as a manifestation of desire, to critique the oppressive constraints placed on female sexuality and identity. Her inner conflict between social expectation and personal instinct operates beneath the surface of the horror, adding psychological depth and ambiguity to a genre often associated with moral binaries. Nevertheless, the broader impact of the Code was to entrench a narrow, conservative vision of female identity, one that marginalized complexity in favor of moral simplicity and domestic virtue.

2. The 1960s-1970s: Women as Both Victims and Survivors

2.1 The Final Girl Trope

As the influence of the Production Code began to wane in the late 1950s and ultimately collapsed in the 1960s, a shift in cinematic representation took hold. Filmmakers gradually reintroduced complex, multidimensional female characters, echoing the bold storytelling of the silent and pre-Code era. This resurgence was particularly visible in the horror genre, where women reemerged not only as victims, but also as survivors, antagonists, and central figures with agency. The official end of the Hays Code in 1968, replaced by the MPAA rating system, reopened the space for more explicit content, psychological depth, and gender complexity in American cinema. Horror, once again, became a fertile ground for exploring transgression, especially regarding women’s roles. This post-Code era witnessed the gradual reemergence of female agency on screen, though often within newly codified tropes shaped by both feminist and patriarchal anxieties.

The 1960s and 1970s therefore marked a pivotal transformation in the representation of women in horror cinema. While female characters were still frequently positioned as victims, for example, Marion Crane in Psycho (Alfred Hitchcock, 1960), whose murder in the film’s first act is both shocking and emblematic of female vulnerability, or Rosemary in Rosemary’s Baby (Roman Polanski, 1968), whose body becomes the battleground for male control and demonic reproduction, this era also introduced a new archetype that would reshape the genre for decades to come: the “Final Girl.” Coined by film scholar Carol J. Clover, the Final Girl refers to the last surviving female character who confronts the killer and often outlives all other characters ((In Psycho (1960), Marion Crane initially appears as the central character but is shockingly killed off early, subverting traditional horror expectations. Her sister, Lila Crane, then takes on the role of the proto-Final Girl. Unlike Marion, Lila is persistent and brave, actively investigating Norman Bates’ eerie motel and uncovering his dark secret, embodying a shift toward female characters who are not just victims but agents of truth and survival.)). She is typically resourceful, observant, and morally distinct from her peers, traits that position her as both a survivor and a vehicle for audience identification. The Final Girl often takes an active role in defending herself and ultimately killing the killer. Clover characterizes her as “boyish,” watchful, intelligent, resourceful in a crisis, often virginal, and usually distinct from the rest of her friend group as the outsider. Audiences identify with her because psychologically, she is the most realistic character: she recognizes the danger and is the one who fights back (Clover, 1992).

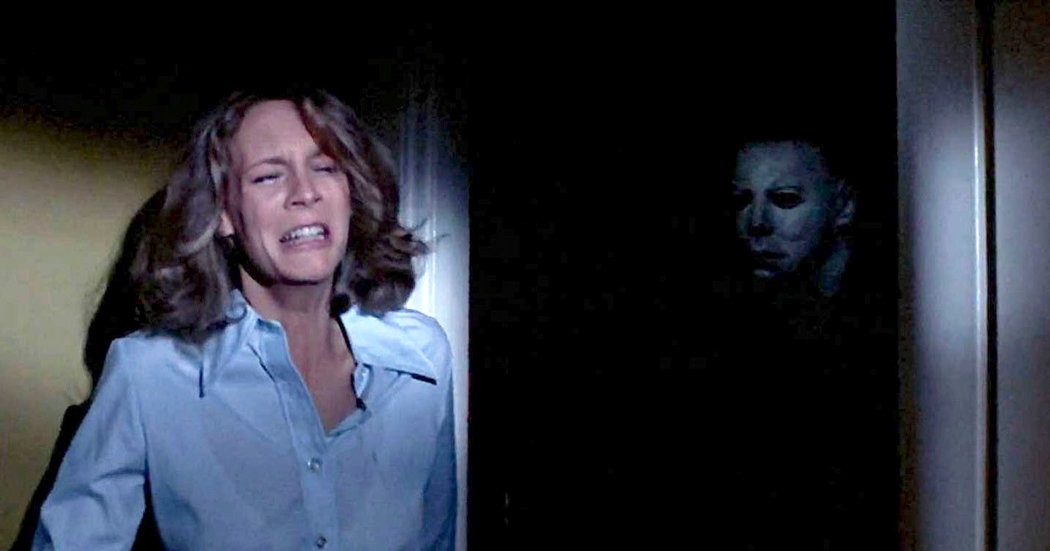

The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (Tobe Hopper, 1974) introduces Sally Hardesty, a young woman who endures horrific terror at the hands of the murderous Sawyer family. Sally’s survival is redefined through her intense psychological and physical resilience; she escapes her captors not by pure luck but through sheer determination and grit, illustrating a more realistic and harrowing portrayal of female endurance. Laurie Strode in Halloween (John Carpenter, 1978) perhaps best exemplifies the Final Girl trope. Laurie is intelligent, observant, and resourceful, qualities that set her apart from earlier horror heroines. Throughout the film, she uses her wits to evade and ultimately confront the relentless killer Michael Myers. Laurie’s survival is not passive but an active struggle, marking a significant evolution in how female characters in horror assert agency and resilience. Together, these characters helped redefine female survival in horror by shifting the focus from women as mere victims to complex protagonists who face danger head-on, use their intelligence and courage to survive, and often serve as the moral center of the narrative (Lympus, 2024).

This representational shift in horror cinema did not occur in isolation but rather reflected broader social changes happening at the time. The 1960s and 1970s were marked by key feminist movements that reshaped the cultural landscape for women. Second-wave feminism emerged, advocating for gender equality in education, employment, reproductive rights, and sexual freedom. This movement was sparked in part by Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique (1963), which critiqued the role of women as housewives and led many to question societal expectations. In 1966, the National Organization for Women (NOW) was founded, pushing for changes like the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA) and the right to abortion. A pivotal moment in the fight for reproductive rights came in 1973 with the Supreme Court’s decision in Roe v. Wade, which legalized abortion nationwide. The sexual revolution, fueled by the introduction of birth control, also empowered women to take control of their sexual autonomy, challenging traditional views of women in marriage and relationships. Legislative reforms such as the Equal Pay Act (1963) and Title VII of the Civil Rights Act (1964) aimed to dismantle workplace discrimination, further advancing women’s rights. These cultural and political shifts were foundational in challenging traditional gender roles and were reflected in the evolving portrayals of women in media, including horror films, during this transformative period (Mehls, 2015).

Yet despite this evolution in female representation, traces of conservatism remain embedded within the genre. The Final Girl, while offering a striking contrast to earlier portrayals of passive female victims, often survives by adhering to specific behavioral codes: she is typically characterized as sexually restrained, morally upright, and emotionally composed. In contrast, her more sexually assertive or rebellious counterparts are frequently eliminated early in the narrative. This dynamic reveals that even the seemingly empowering figure of the Final Girl is shaped by the genre’s ongoing compromise with traditional gender norms. She may mark a step forward, but her survival often hinges on reinforcing deeply ingrained cultural ideals about femininity, virtue, and control, reminding us that progress in representation can coexist with underlying conservatism in the film industry.

2.2 Horror films and the Male Gaze

This emergence of the Final Girl as a resilient survivor is particularly notable given the traditionally male-dominated perspective of mainstream cinema. To fully understand the significance of this trope, it is essential to consider the role of the male gaze, a concept articulated by Laura Mulvey, which highlights how Hollywood films often position women as objects of male visual pleasure.

This conceptualization of the functionality of the male gaze in Hollywood cinema is made even more explicit, and arguably more perverse, when subject to a practical application related to the horror genre. Narcissistic scopophilia is manifested through the familiar generic convention of placing the audience in the monster or killer’s point of view. The spectator is privy to the killer’s perspective as he covertly stalks his intended targets. As he hides in closets (Halloween), attics (Black Christmas, Bob Clark, 1974), or peeks through a secret spyhole (Psycho), the killer employs Mulvey’s sadistic, voyeuristic gaze as he watches his victims shower, make love, or disrobe, imposing the violence of his intrusive and curious gaze upon his unaware object of desire. The complicity of the spectator in the woman’s victimization is reflected through the use of the point of view shot; the spectator “sees” through the eyes of the killer; when he looks down it is the killer’s hands that he sees as his own. When he gazes upon the female form laid bare for the sake of visual pleasure, his gaze becomes unified with that of the killer. The pleasure experience is then a communal and shared one; by way of the camera’s gaze, the spectator is involuntarily forced into identification with the killer.

At the time, the Final Girl was designed primarily for a male audience, as it was believed that teenage boys were the main viewers of horror films centered around serial killers during the ’70s and ’80s. The female characters in these films were crafted to satisfy the “male gaze”, a concept that links female attractiveness to audience appeal, shifting viewers’ identification from the killer to the female protagonist. In such films, the Final Girl stands out as the only fully developed character and filmmakers intentionally underdevelop the supporting cast to highlight her early on. Some critics argue that this dynamic forces male viewers into a complex psychological position: they must mentally “submit” by identifying with the Final Girl’s vulnerability and suffering, rather than a traditional male hero’s dominance. This is unusual because the Final Girl embodies both victim and survivor, making the male audience experience fear and empowerment through her. Since there is no conventional male protagonist to root for at the end, the Final Girl takes on qualities typically associated with masculinity, such as intelligence, courage, and resilience. By adopting these traits, she becomes a kind of masculinized figure of strength and agency, challenging traditional gender roles within the horror genre and redefining what it means to be a heroine in these films.

The emergence of the Final Girl therefore marks a significant evolution in horror cinema. Women were no longer just passive victims to be saved or sacrificed, they became survivors: vigilant, adaptable, and by the film’s conclusion, often stronger than their male counterparts. This era laid the foundation for future horror films to explore female strength, trauma, and agency in increasingly complex and sometimes subversive ways.

3. The 1980s-1990s: The Stereotype Evolution and Subversion

3.1 Slasher films

The 1980s and 1990s saw a sharpening of the cultural contradictions surrounding women’s roles, as gains from 1970s feminism, expanded access to education, professional advancement, and political agency, were met with a growing conservative backlash that idealized traditional family structures and gender norms, especially during the Reagan era. This tension became particularly visible in popular culture, and horror films were a key site where it played out. During this period, the figure of the Final Girl rose to prominence, a character who, while surviving the horror, often did so by embodying traditional virtues such as chastity, caution, and moral clarity. Her survival was less about subverting the system and more about conforming to it.

At the same time, the genre began to popularize a new archetype: the “strong woman” protagonist, as seen in characters like Ellen Ripley (Aliens, 1986) or Sarah Connor (Terminator 2, 1991). These figures displayed physical strength, leadership, and autonomy, stepping into roles typically occupied by male action heroes. However, even these characters were not free from gendered expectations, they were often framed through narratives of maternal sacrifice or emotional repression, reinforcing a different but still limiting version of femininity.

Together, the rise of the Final Girl and the strong female lead reflect the deep ambivalence of the era: a simultaneous desire for female empowerment and a cultural need to contain it. Rather than signaling full emancipation, these figures often illustrate the compromises women were expected to make, surviving, or thriving, only by adhering to certain acceptable forms of strength or virtue.

These tropes are particularly used in the slasher genre, which gained popularity in the 1980s. A slasher film is defined by Carol J. Clover as “[an] immensely generative story of a psycho killer who slashes to death a string of mostly female victims, one by one, until he is himself subdued or killed, usually by the one girl who has survived, which often portrayed women in highly sexualized, victimized roles” (1992, 21). Films like Friday the 13th (Sean S. Cunningham, 1980) and A Nightmare on Elm Street (Wes Craven, 1984) capitalized on the formula of sexual liberation followed by brutal punishment, with female characters often serving as the victims of a violent, faceless antagonist. These films reflected a societal paradox where women were depicted as sexually liberated but punished for deviating from traditional gender norms. The slasher genre, while enabling women to express their sexuality, simultaneously reinforced the notion that sexual freedom was dangerous, often showing women who were killed or tortured after engaging in promiscuous behavior. For instance, in A Nightmare on Elm Street, the character Nancy Thompson’s friends who engage in sexual activity are among the first victims of Freddy Krueger, reinforcing the deadly consequences of their behavior within the narrative. This pattern echoed the broader cultural anxieties about the perceived moral decay of society in the post-sexual revolution era, where women’s growing sexual autonomy was still met with caution and fear.

The denunciation by theorists, critics, audiences and feminists of this conception of the horror genre is most frequently rooted in its tendency to cast women as the victims of sadistic, male violence. Cynthia A. Freeland dismisses the genre as “anti-woman,” citing numerous generic examples of graphic violence perpetrated upon onscreen representations of women (Freeland, 1995). The onscreen woman falls victim to the monster or, in the case of the immensely popular slasher subgenre, the killer who brutalizes their victims with an array of phallic weaponry intended to mutilate, eviscerate and “open up” the female body for audiences to bear witness to gratuitous displays of the spectacle of the ruined body. The low-brow, visceral quality of the genre, as James Twitchell has described it (Twitchell, 1985), has been argued to not only perpetuate sexist ideals, but additionally, evoke real-world reenactments of onscreen violence. So prevalent is the image of the female victim in horror that she has been transformed into a caricature of feminine representation; the screaming, dim-witted, scandalously attired, sexual object has become a cornerstone of the modern horror film. While open to critique and parody through this representation’s oversaturation, the image of woman as victim in horror also sanctions a theoretical inquiry into the deeper social and political implications of female victimization from onscreen images to real world examples.

3.2 Alternative representations

Despite these entrenched depictions, alternative portrayals of women in horror have emerged that challenge this victim narrative. Another example of an empowered woman in horror is Gail Weathers from Scream (Wes Craven, 1996). As Scream is a postmodern deconstruction of the slasher genre, it embraces the Final Girl trope with a twist. Gail, a journalist, is both tough and resourceful, challenging the typical victim narrative. Her character is no longer bound by passive innocence but instead possesses intellect, courage, and a clear willingness to fight back, even though she is not the “innocent virgin” character that many horror films have historically centered.

This evolution in female representation is part of a broader shift that took shape during the 1980s and 1990s, a period which also saw the rise of stronger, more active female protagonists who fought back against the horrors they faced. Perhaps the most iconic example is Ripley from Alien (Ridley Scott, 1979), a character whose transformation from a crew member trying to survive a dangerous extraterrestrial creature to the ultimate action heroine was groundbreaking. In Aliens (1986), Ripley’s role as a fierce mother figure and military leader solidified her as a cultural icon of female strength. Ripley is a character who does not just survive; she takes charge, exhibits leadership, and is unapologetically tough, traits traditionally reserved for male action heroes (Mehls, 2015).

Another notable example is Sarah Connor from The Terminator (James Cameron, 1984) and Terminator 2: Judgment Day (James Cameron, 1991). Though often categorized as science fiction or action, both films incorporate strong horror elements, particularly in the first installment, which shares many characteristics with slasher films: a relentless, nearly indestructible killer stalking a vulnerable woman, high levels of suspense, and graphic violence. In The Terminator, Sarah begins as a victim, hunted by a cyborg assassin, but by Terminator 2, she transforms into a formidable fighter, a mother fiercely protecting her son and a survivor willing to confront a seemingly unstoppable threat. This transition from victim to active protagonist mirrors the increasing independence and agency women were gaining in the real world during the 1980s and 1990s, as they entered the workforce in greater numbers and claimed more autonomy over their lives.

Characters like Ripley and Sarah Connor in the 1980s and 1990s embody this complex negotiation between empowerment and traditional gender expectations. These characters demonstrated that women could be strong, independent, and capable of surviving horrific circumstances, but their strength was framed within contexts that aligned with maternal or protective instincts. Horror films of this era, therefore, offer a lens into the cultural shifts of the time, where women were gradually gaining more agency, but were still expected to fit within socially acceptable roles defined by gender norms.

4. The 2000s and Beyond: Intersectionality and Empowerment

The 2000s and beyond mark a profound ideological and creative shift in horror cinema, where female representation has evolved from passive archetypes to active, multidimensional agents shaped by empowerment, trauma, and identity. Unlike earlier decades that relied on the “Final Girl” trope or sexualized victims, contemporary horror interrogates, deconstructs, and reimagines those roles. Female characters are no longer just survivors; they are emotionally complex protagonists whose interiority and struggle drive the horror itself.

4.1 The Emotional Complexity of Motherhood and Grief

Films like The Babadook (Jennifer Kent, 2014) reframe motherhood, traditionally idealized in cinema, as a space of psychological turmoil. Amelia, a grieving single mother, is not simply haunted by a monster but consumed by trauma and unprocessed sorrow. Horror here becomes a metaphor for inner collapse, not just external threat.

Similarly, Midsommar (Ari Aster, 2019) explores the emotional rebirth of Dani, a woman crushed by personal loss and emotional neglect. Her journey through grief culminates not in traditional healing but in catharsis through a violent, cult-driven reinvention of self. These films do not merely showcase “strong women”, they depict emotional depth, vulnerability, and rage as sources of power.

4.2 Intersectional Horror: Race, Migration, and Identity

What distinguishes this era even further is its embrace of intersectionality. Horror no longer defaults to white, cisgender, straight women as its protagonists. In Get Out (Jordan Peele, 2017), although the lead is male, the film reframes the racial and gender dynamics of horror. Rose, the white female antagonist, uses her race and femininity as tools of control and violence, a subversion of the traditional “damsel in distress”.

Likewise, Nanny (Nikyatu Jusu, 2022) centers on Aisha, a Senegalese immigrant haunted by spirits from her homeland. The horror she faces stems not only from the supernatural but from systemic exploitation, displacement, and racialized trauma. These films affirm that female horror is not monolithic; it is shaped by cultural, racial, and social position.

4.3 Feminist Reappropriation and the #MeToo effect

The reappropriation of horror codes with a feminist agenda becomes especially visible in The Witch (Robert Eggers, 2015), which predates the #MeToo movement but resonates powerfully with its themes. Thomasin’s transformation from a repressed Puritan girl to a liberated witch is not portrayed as a descent into evil, but as an act of emancipation from patriarchal violence. Her choice is one of autonomy, not damnation.

However, even films praised for engaging with #MeToo themes, such as Leigh Whannell’s The Invisible Man (2020), have their limitations. Loosely based on H.G. Wells’s novel, the film follows Cecilia Kass (Elisabeth Moss) as she escapes an abusive relationship with Adrian, a wealthy optics engineer. After learning of Adrian’s apparent suicide, Cecilia begins to sense an unseen presence stalking her, later revealed to be Adrian himself, using an invisibility suit to torment her. In a Vogue article, Taylor Antrim commended the film for centering Cecilia’s experience: “a story of trauma and what it means to not be believed, and there’s not a breath of exploitation on screen” (Grierson, 2020) The film avoids sensationalism, exaggerated or graphic depictions meant more to shock than to explore trauma. Still, it follows a familiar pattern: Cecilia is dismissed and disbelieved until she takes violent action into her own hands. This raises a key question as to whether she finds real healing, or simply momentary release through revenge, suggesting that while the film highlights trauma and survival, its portrayal of resolution leans more toward temporary reprisal than lasting healing.

More successfully, Jennifer’s Body (Karyn Kusama, 2009), initially misunderstood and mis-marketed, has since been reclaimed as a feminist cult classic. At the time of its release, the film was heavily promoted as a teen sex comedy, capitalizing on Megan Fox’s image and objectifying her in the marketing material. Trailers emphasized titillation over substance, targeting a young male audience rather than the film’s actual core themes of female friendship, betrayal, and repressed rage. This marketing strategy clashed with the film’s satirical, subversive tone and alienated the very audience, young women and queer viewers, who might have connected most with its message. As a result, the film was dismissed by critics and failed at the box office. Only years later, especially in the context of the #MeToo movement, did audiences and scholars begin to recognize its deeper commentary: a searing metaphor for how women are consumed, silenced, and then demonized, and how that rage can become a form of reclamation.

Unlike many genres that shied away from the implications of #MeToo, horror embraced them head-on. It became a space where women could be portrayed not as symbols or victims, but as complex figures grappling with grief, agency, anger, and power. These films do not resolve trauma with clean redemption arcs, they expose it, confront it, and weaponize it. Contemporary horror now stands as one of the most politically charged and narratively radical spaces in modern cinema. Far from being escapist, it is a genre of exposure, where the real monsters are often social structures, and survival means far more than staying alive.

Conclusion

The portrayal of women in horror cinema is not merely a reflection of changing societal attitudes, it is a battleground where cultural anxieties about gender, power, and agency are both staged and contested. Far from static, female representation in horror has undergone a dramatic transformation, evolving from the subversive and complex figures of the silent era, to the helpless, moralized victims of the Hays Code period, to the emergence of the Final Girl trope in the 1960s and 70s, a figure who both upholds and disrupts patriarchal norms. The 1980s and 90s brought a new wave of seemingly empowered women, yet these characters often remained trapped in hypersexualized or binary roles. Horror has long exploited female suffering for shock value, but it has also served as a space for reimagining women as survivors, avengers, and even as the source of fear itself. These shifting portrayals are not incidental; they are symptomatic of broader struggles over women’s autonomy and societal place. As a genre fundamentally concerned with fear, horror cinema uniquely reveals how femininity is constructed, threatened, and renegotiated in the cultural imagination.

Notes

Bibliography

CARROLL, Noël. 1990. The Philosophy of Horror, or Paradoxes of the Heart. New York: Routledge.

CLOVER, Carol J. 1992. Men, Women, and Chain Saws: Gender in the Modern Horror Film. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

HANKINS, Sarah. 2020. “‘Torture the We the Women’: A Gaze at the Misogynistic Machinery of Scary Cinema”, Copley Library Undergraduate Research Awards. URL: https://digital.sandiego.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1000&context=library-research-award

JEFF, Leonard J. and SIMMONS, Jerold (eds.). 1990. The Dame in the Kimono: Hollywood, Censorship, and the Production Code from the 1920s to the 1960s. New York: Grove Wiedenfeld.

LEWIS, Jon. 2021. Hollywood v. Hard Core: How the Struggle Over Censorship Saved the Modern Film Industry. New York: NYU Press.

LYMPUS, Claire. “The Evolving Depiction of Female Characters in the Horror Film Genre”, The Philosophy, Politics, and Economics Review, 23 January 2024. URL: https://pressbooks.lib.vt.edu/pper/chapter/the-evolving-depiction-of-female-characters-in-the-horror-film-genre/

MALONE, Alicia. 2023. Girls on Film: Lessons from a Life of Watching Women in Movies. Philadelphia: Running Press.

MEHLS, Robert. 2015. In History No One Can Hear You Scream: Feminism and the Horror Film 1974-1996. Master’s Thesis, University of Colorado Boulder.

MULVEY, Laura. 1975. “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema.” Screen, Vol. 16, No. 3, pp. 6–18.

SCHUBART, Rikke. 2007. Super Bitches and Action Babes: The Female Hero in Popular Cinema, 1970-2006. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company.

SPARKS, Glenn G. and SPARKS, Cheri W. 2000. “Effects of Media Violence”, in Dolf Zillmann, and Peter Vorderer (eds.), Media Entertainment: The Psychology of Its Appeal, Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, pp.269-286.

SPOTO, Donald. 1983. The Dark Side of Genius: The Life of Alfred Hitchcock. Boston: Little, Brown and Company.

TANGCAY, Jazz. 2023. “Hollywood’s Forgotten Women: Silent-Era Pioneers Who Shaped the Industry”, American Film Institute.

TWITCHELL, James B. 1985. Dreadful Pleasures: An Anatomy of Modern Horror. New York: Oxford University Press.

WOOD, Robin. 1986. “The American Nightmare: Horror in the 70s”, in Barry Keith Grant (ed.), Planks of Reason: Essays on the Horror Film. Metuchen, NJ: Scarecrow Press, pp.164-200.

Further reading

BRITTAIN, Amy. “Me Too Movement: Definition, History, Purpose, & Societal Impact”, Encyclopædia Britannica, 16 May 2025. URL: https://www.britannica.com/topic/Me-Too-movement

DE ROZARIO, Ghill. “Women in Horror - Are Horror Movies Inherently Misogynistic, or Are They Just Misunderstood?”, Medium, 10 June 2015. URL: https://medium.com/@Ghill_deRozario/are-horror-movies-inherently-misogynistic-or-are-they-just-misunderstood-76990d8753aa

DERR, Jess. 2022. Surviving More Than Monsters: Post-Horror in the Age of #MeToo. Master’s Thesis, under the supervision of Jean Lutes and Megan Quigley, Villanova University. URL: https://search.proquest.com/openview/c2646f79c8252290ec2a20af3ac0805a/1?cbl=18750&diss=y&pq-origsite=gscholar

HART, Hannah. 2024. Monstrous Mothers and Final Girls: Representations of Women in Horror Films. Senior Thesis, Scripps College.

LIBERMAN, Tom. “The Hays Code and Its Effect on Strong Women in Hollywood”, Tom Liberman’s Blog, 4 May 2020. URL: https://www.tomliberman.com/entertainment/the-hays-code-and-its-effect-on-strong-women-in-hollywood

MARTIN, Jessica. 2020. “#MeToo?: The Intersectional Reach and Limits of a Social Movement.” CORE, 15 October 2020. URL: https://core.ac.uk/download/323028984.pdf

O'BRIEN, Chelsey. 2020. “Early Hollywood and the Hays Code”, Australian Centre for the Moving Image (ACMI), 4 May 2020. URL: https://www.acmi.net.au/stories-and-ideas/early-hollywood-and-hays-code/

PEREZ GUILLERMO, Gilberto. “Shadow and Substance: F.W. Murnau’s Nosferatu”, Sight & Sound, 4 March 2022. URL: https://www.bfi.org.uk/sight-and-sound/features/shadow-substance-f-w-murnaus-nosferatu

POULTER, Avery. “The Feminine Future of The Terminator”, The Common Room, 23 January 2024. URL: https://knoxcommonroom.wordpress.com/2024/01/23/the-feminine-future-of-the-terminator/

SCREAMPSYCHOHORROR. “Representation of Women in Horror Films”, screampsychohorror, 3 April 2011. URL: https://screampsychohorror.wordpress.com/representation-of-women-in-horror-films/

SMITH, Jane. 2010. The Stereotypic Portrayal of Women in Slasher Films: Then Versus Now. Master’s Dissertation, Louisiana State University. URL: https://repository.lsu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1055&context=gradschool_theses

SOURISSE, Constance. 2023. The (Re)Appropriation of Horror Film Codes with a Feminist Agenda. A Case Study: Jennifer’s Body. Master’s Thesis, University of Toulouse II - Jean Jaurès. URL: https://dumas.ccsd.cnrs.fr/dumas-04103428v1

VOSPER, Amy Jane. 2014. “Film, Fear and the Female: An Empirical Study of the Female Horror Fan”, Offscreen, volume 18, n°6-7. URL: https://offscreen.com/view/film-fear-and-the-female

WAX, Alyse. 2024. “What Is a Final Girl? Examples From Horror Movies + Acting Tips”, Backstage, 27 September 2024. URL: https://www.backstage.com/magazine/article/final-girl-horror-movies-explained-77788/

Cette fiche a été rédigée dans le cadre d'un stage à l'ENS de Lyon.

Pour citer cette ressource :

Reda Boulkhiam, Beyond the Damsel in Distress: The Evolution of Female Representation in American Horror films, La Clé des Langues [en ligne], Lyon, ENS de LYON/DGESCO (ISSN 2107-7029), septembre 2025. Consulté le 19/02/2026. URL: https://cle.ens-lyon.fr/anglais/arts/cinema/beyond-the-damsel-in-distress-the-evolution-of-female-representation-in-american-horror-films

Activer le mode zen

Activer le mode zen