All men are created equal? Barack Obama and the American Revolution

Télécharger le Power Point de Steven Sarson [PDF]

Introduction

This presentation is about the language Barack Obama uses as well as his interpretation of American history. I will try to show how he uses language to reinforce historical interpretation in a way that is very clever and that you would not get with his successor. What we see through Obama is an interpretation of American history that presents the American Revolution as something that is not finished yet, but has been ongoing since the Revolution itself.

Why is it interesting to look at the American Revolution through Barack Obama’s eyes? One reason is that, listening to his speeches and reading his book when he first campaigned for the presidential election in 2008, and observing how attuned he was to American history, it is quite striking to see how much it informed his politics, his values as well as his policies, his ideologies as well as his ideas, and how much he actually knew about it. Moreover, analysing our interpretation of history, and not just the facts, is a good way get into the analysis of history.

Barack Obama takes the American Revolution not just as something that is contained in time; the ideas of the American Revolution have evolved throughout American history, in particular with the abolition of slavery and segregation. The abolition of slavery may therefore be seen as an extension of the American Revolution to the 1860s, and then the abolition of Jim Crow laws a hundred years later as a further extension of the ideas of liberty and equality that were there from the founding of the U.S.

One of the things that may be noticed about Barack Obama’s many references about American history is how often he cites the founding documents of the Declaration of Independence of 1776 and the Constitution drafted in 1787, ratified in 1788 and implemented in 1789.

1. Quoting the Declaration of Independence

1.1 Keynote Speech at the DNC, 2004

I have selected a few extracts of his speeches where he refers to the Declaration of Independence: unsurprisingly, Barack Obama mentions the Declaration during big occasions, when he would have the largest audiences.

Barack Obama’s first ever national speech was a keynote address at the Democratic National Convention in Boston in 2004: he had been noticed and picked out by the John Kerry campaign that year to give this important speech – Bill Clinton had done it before, it is a real breakthrough for any politician trying to make it and maybe one day run for president. This is what Obama said in his first inaugural address:

Our pride is based on a very simple premise, summed up in a declaration made over two hundred years ago, "We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal. That they are endowed by their Creator with certain inalienable rights. That among these are life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness."2004 Democratic National Convention keynote address (prepared remarks)

He quotes the Declaration word for word, and talks about the God-given promise that all are equal, all are free, all deserve a chance to pursue their full measure of happiness, which is an idea contained in the Declaration.

1.2 Second Inaugural Address, 2013

His second inaugural address also refers to the Declaration and defines it as what makes America exceptional:

What makes us exceptional—what makes us American—is our allegiance to an idea articulated in a declaration made more than two centuries ago:"We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal; that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights; that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness."Second Inaugural Address by President Barack Obama, 2013

There is a close identification of the nation with that founding document and the ideas contained within it.

1.3 Farewell Address, 2017

Finally, Obama mentions the Declaration of Independence in his farewell address, in which he had to find a balance between his belief in the historical progress of the values and ideals of the Declaration and the outcome of the 2016 presidential election.

Does the election of Donald Trump wipe Obama out? Is Obama an exception or is he a mark of progress? The pretty sophisticated way in which Obama talked about that very issue in his farewell address was to reiterate his belief in long-term progress. But more often than not, progress is not linear: sometimes you go backwards. Obama said many times that the road to democracy is long and hard. Sometimes it seems you take two steps forward and then one step back. Obama’s election was an emblem of growing equality, but Trump's election reminds us that the fight for equality is still ongoing. There are days where you lose the battle, but you must keep on fighting the war.

Obama talked in his farewell address about “…. the conviction that we are all created equal, endowed by our Creator with certain unalienable rights, among them life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.” ("My Farewell Address", 2017. Source: The White House)

Despite the election of Donald Trump, and everything backwards that it represents, Obama still believed in those principles.

2. Quoting the Constitution

Obama also quotes the Constitution often: he tries to relate the Declaration of Independence to the Constitution as the first moment of progress in American history. His idea is that the Declaration’s values are embedded in the Constitution, which is actually historiographically quite controversial. Historians have this argument about whether they believe, as Obama does, that the values of the Declaration are indeed embedded institutionally in the Constitution or whether the Constitution, with its enormous power structure, created a government that was designed to suppress the spirit of 1776 and the radical ideas that appear in the Declaration. I personally think that it is a bit of both. It is very hard to say because the point of the Declaration was to break away from Britain; the point of the Constitution was to create a new government. They therefore have very different purposes: breaking away from a government inherently means being anti-power; creating a new government inherently means talking about power. It is not fair to compare the Declaration and the Constitution in this invidious way, because they have such different purposes.

2.1 “A More Perfect Union,” Philadelphia, 2008

Obama therefore sees the Declaration as embedded in the Constitution in many ways, and we can see the relationship between the two in a speech he made in Philadelphia in March 2008. His campaign was going pretty well at that point, and he was ahead of Hillary Clinton in the Democratic primary. However, he got a bit side-tracked because his pastor, Reverend Jeremiah Wright, had made some quite controversial comments about 9/11 being America’s chickens coming home to roost, and had talked about the inherent racism in American domestic and foreign policy – he had used the term “God dam America”, which is pretty inflammatory language, especially in American cultural context. Obama answered those comments in his speech, and at the same time laid out the groundwork of his beliefs about American history.

‘We the people, in order to form a more perfect union.'Two hundred and twenty one years ago, in a hall that still stands across the street, a group of men gathered and, with these simple words, launched America’s improbable experiment in democracy. Farmers and scholars; statesmen and patriots who had travelled across an ocean to escape tyranny and persecution finally made real their declaration of independence at a Philadelphia convention that lasted through the spring of 1787.

The document they produced was eventually signed but ultimately unfinished. It was stained by this nation’s original sin of slavery, a question that divided the colonies and brought the convention to a stalemate until the founders chose to allow the slave trade to continue for at least twenty more years, and to leave any final resolution to future generations.

Of course, the answer to the slavery question was already embedded within our Constitution – a Constitution that had at is very core the ideal of equal citizenship under the law; a Constitution that promised its people liberty, and justice, and a union that could be and should be perfected over time.”

The speech exemplifies the linguistic subtleties of Obamaian rhetoric. “We the people, in order to form a more perfect union” is rendered in quote marks in all the transcripts. But there’s an elision there: the actual Constitution says “We the people of the United States”. I think this elision is deliberate. But what does it mean? At the end of the 18th century, African Americans made up 20% of the US population, but they were mostly slaves. They were considered to be among “the people”, but they were not “of the United States”. This is one of the subtle ways in which Obama signals a slightly more radical and critical interpretation of American history, without being actually explicit about it. He has two audiences: a black audience that will hear the omission of “of the United States”, and a white audience who might not hear it.

Barack Obama goes on to say: “Two hundred and twenty one years ago, in a hall that still stands across the street, a group of men gathered and, with these simple words, launched America’s improbable experiment in democracy. Farmers and scholars; statesmen and patriots who had travelled across an ocean to escape tyranny and persecution finally made real their declaration of Independence at a Philadelphia convention that lasted through the spring of 1787.”

In saying that the Founders at that Convention “made real the Declaration of Independence in a Constitution”, Obama appears to stating a historical fact but is in fact advancing a historical interpretation. While Obama claims here that the ideas of equality and liberty embedded in the Declaration were translated into the Constitution. Many historians, on the other hand, argue that the Constitution was intended to roll back advances toward equality and liberty that many Founders believed had gone too far since and partly because of the Declaration.

In other words, Obama credits the Constitution with the creation of a “democracy” that according to some historians it was meant to inhibit. Indeed Obama furthermore refers to “America’s improbable experiment in democracy”. At the time, however, the term “democracy” usually meant the direct rule of the people, something that even radicals like Thomas Jefferson equated with mob rule and descent into anarchy. What the Founders favoured in fact was what they called “republicanism,” a term that then implied the representation of the people in government, a representation appropriately checked and balanced by law and therefore a very different thing from democracy’s direct rule and absolute power. It was only in the middle of the 1790s that Americans began using the term “democracy” in the same looser way we do—to imply the representation rather than the direct rule of the people.

Obama exaggerates here the extent of democracy as an aim of the American Revolution. He then he does it again in a sort of social-democratic way: “Farmers and scholars; statesmen and patriots”. Mentioning manual workers and intellectuals in the same sentence underscores the fact that, according to Obama’s views on democracy, anyone can become a statesman. This is not a European idea, this is a very American ideal. It is all embedded in this speech, in Obama’s rapid run through of the American Revolution.

This brings to mind John Dickinson, who was one of the pamphleteer against Britain and is now known as the penman of the American Revolution. He wrote a pamphlet called Letters from an American Farmer. He pretended to be a farmer – he was actually a big planter with lots of slaves, a lawyer and a politician – and he is one of these early Americans who pretended to be from a log cabin, but really was not.

Obama describes these revolutionaries, these farmers, scholars, statesmen and patriots as having travelled across an ocean to escape tyranny and persecution and then they made real their Declaration of Independence. But it actually was the pilgrims and the Puritans in 1620-1630 who travelled across an ocean to escape tyranny. They did not live long enough to declare their independence. Obama knows the difference in time, the century and a half or more between these events. This is another elisional collapse of time: he is trying to send the American Revolution back in time, to the founding of the colonies, to show that America has always been about freedom, from the very founding of this land as an American land (as opposed to Native American land). There might not have been liberty and equality at that time, but there was at least a pursuit of happiness by these people.

In this speech, they are also conflated with the revolutionaries themselves, which magnifies the achievements of both – the founding of America and the founding of the United States. Obama knows the difference: he says this deliberately, as his speeches are carefully constructed.

There is one more elision in “the spring of 1787”. The Constitutional Convention that he is referring to first met on May 20th, and sat until September 17th: that’s the summer, not the spring. Barack Obama has taught constitutional law at the University of Chicago for twelve years. He was summa cum laude at Harvard law school. He was the President of the Harvard Law Review. He knows when the Constitution sat. So why say spring? Spring is about newness, new light, new life. He has done a similar thing with the American Revolution: he talked about British colonial rule as a kind of winter, evoking blood on the snow. He places the birth of the United States is the spring: although it is not technically true, there is a metaphorical truth in the way he presents it. It is also about creating an image in the memory of Americans and conveying a certain conception of American history.

Nevertheless, he knew about inequalities in early America and mentions them: one of the purposes of that 2008 speech was to create a balance between the anger that Reverend Jeramiah Wright expressed and the optimism about America and its history that Obama himself represents. He says:

“The document they produced was eventually signed but ultimately unfinished. It was stained by this nation’s original sin of slavery, a question that divided the colonies and brought the convention to a stalemate until the founders chose to allow the slave trade to continue for at least twenty more years, and to leave any final resolution to future generations.”

Obama is making an assumption about the Founders themselves: he believes they thought they coul not fix slavery at that time, and therefore compromised and set the conditions for the next generation to end the slave trade. It actually took three or four more generations to end slave trade, but the founders had nevertheless projected the solution in the future.

The sentence “[…] the answer to the slavery question was already embedded within our Constitution – a Constitution that had at is very core the ideal of equal citizenship under the law; a Constitution that promised its people liberty, and justice, and a union that could be and should be perfected over time” shows that Obama is projecting the American Revolution from its own time into the future and that it was, he implies, the intention of the Revolution: they were not going to create a perfect society straight away, but they would state values by which it would be created in the future.

What Obama has argued so far is that the Founders themselves projected American values of equality and liberty into the future, arguing that they will happen one day: it is one thing to do that from the past, but it is a different thing to look at that from the point of view of the future.

2.2 “For We Were Born of Change,” Selma, Alabama, 2015

There are places where Obama does that, when he talks, not about what the Founders intended, but about looking back at what was reaped from their words. He gave a speech in 2015 in Selma, Alabama to commemorate the fiftieth anniversary of the Voting Rights March. He says:

What greater expression of faith in the American experiment than this, what greater form of patriotism is there than the belief that America is not yet finished, that we are strong enough to be self-critical, that each successive generation can look upon our imperfections and decide that it is in our power to remake this nation to more closely align with our highest ideals?“For We Were Born of Change,” Selma, Alabama, 2015

Again, there is that difference between ideals and reality; the ideals give a sense that we can aim for that new reality. Obama tries to bring African American history in mainstream American history, and that is the most radical form of historical interpretation that he does. Even today, when American history is presented, there is American history and then there is this “unfortunate” African American history: those are two parallel lines. Obama makes them part of the same story: Selma is not an outlier, it is central in American history. The disenfranchisement and the Civil Rights Movement are central parts of the country’s history, not some sidebar in a textbook.

That’s why Selma is not some outlier in the American experience. That’s why it’s not a museum or a static monument to behold from a distance. It is instead the manifestation of a creed written into our founding documents:‘We the People…in order to form a more perfect union.’‘We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal.’“For We Were Born of Change,” Selma, Alabama, 2015

We saw the elision of “of the United States” in the 2008 speech in Philadelphia: African Americans were slaves, so they could not be of the United States, even though they were in “the people”. Here, the wording is slightly different. Constitutionally, America was an equal country, but in reality, it was not, because of the Jim Crow laws. Plessy v. Ferguson, argued in the Supreme Court in 1896, decided that you could have separate facilities; separate, but equal. So segregation did not violate the 14th amendment – but it was obviously a legal lie. Williams v. Mississippi in 1898 decided that the requirements for voter registration were not based on race; but of course, those requirements disqualified black people from voting.

Each of these three ellipses seems to a constitutional law that was not implemented before the Civil Rights Movement. They represented empty promises, hence this silence that leaves out the words “of the United States”.

Obama’s speech announcing his run for the presidency gives us a clue as to why he sees power in words. He said: “Lincoln believed in the power of words”. Here, in his 2015 speech, Barack Obama finds that power:

These are not just words [about the quotes from Declaration and the Constitution]. They’re a living thing, a call to action, a roadmap for citizenship and an insistence in the capacity of free men and women to shape our own destiny. For founders like Franklin and Jefferson, for leaders like Lincoln and FDR, the success of our experiment in self-government rested on engaging all of our citizens in this work. And that’s what we celebrate here in Selma. That’s what this movement was all about, one leg in our long journey toward freedom.“For We Were Born of Change,” Selma, Alabama, 2015

2.3 The Audacity of Hope, 2006

We can find another clue as to the power of words in the Audacity of Hope, his main book. In this extract, he quotes the Declaration of Independence, and some paragraphs in the book begin in capitals:

‘WE HOLD THESE truths to be self-evident, that all men are Created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness’.

Those capitals are unique to his book: it does not replicate any transcript of the Declaration of Independence that I know of. But it does replicate the sense of 18th century texts and it recreates that sense of scriptural text. And he calls those words “Our common creed”.

The Oxford English Dictionary defines the word ‘creed’ as :

- 1 a. A form of words setting forth authoritatively and concisely the general belief of the Christian Church, or those articles of belief which are regarded as essential; a brief summary of Christian doctrine: usually and properly applied to the three statements of belief known as the Apostles’, Nicene, and Athanasian Creeds.

- 1 b. A repetition of the creed, as an act of devotion.

- 1. c. More generally: A formula of religious belief; a confession of faith, esp. one held as authoritative and binding upon the members of a communion.

- 2 a. An accepted or professed system of religious belief; the faith of a community or an individual, esp. as expressed or capable of expression in a definite formula.

- 2 b. transf. A system of belief in general; a set of opinions on any subject, e.g. politics or science.

- 2 c. Belief, faith (in reference to a single fact). rare.

The meaning of ‘creed’ is therefore religiously based. For Obama, these words carry the force of Scripture: he is a Christian and a believer, although he is always at pains to say that you do not need religion. But they carry for him the same kind of ideological power that religious texts did.

3. All men are created equal

3.1 The Constitution

At the time when Jefferson wrote the words “all men are created equal” and “Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness” and defined them as unalienable rights, he owned two hundred slaves. Throughout the course of his life, he owned six hundred. How do we reconcile all this hypocrisy to these ideals? Those words did not just belong to him: other people could take them and use them for themselves. In January 1777, a petition from slaves in Massachusetts asked for their freedom on the grounds

that your Petitioners apprehend that thay [they] have in Common with all other men a Natural and Unaliable [inalienable] Right to that freedom which the Grat Parent of the Unavers hath Bestowed equalley on all menkind” (DIAPO 12). SO other people can take these ideas forward, whatever we might think of Thomas Jefferson. They ask for slavery to be abolished and it was: in 1780, Massachusetts implemented a new Constitution, which contained the same words as the Declaration of Independence. And slaves brought cases to court saying “this makes us free, slavery is against the law.To The Honorable Counsel & House of [Representa]tives for the State of Massachusitte [Massachusetts] Bay in General Court assembled, Jan. 13, 1777.

In 1781, Quock Walker, a Massachusetts slave won his freedom on the basis that the Massachusetts Constitution of 1780 declared all men to be born free and equal. By 1790, there were no more slaves in Massachusetts.

These words work, they really do have power. Through the Constitution, we can teach that what is special in the US is that particular balance between state governments and the national government; we can teach that the Constitution is grounded on ideas of popular sovereignty. This is not some divine government: this is government from the bottom up, not the top down.

We can of course argue about whether the fifty-five rich white men who drafted the Constitution really were the people of the U.S. But again, what they created would not belong to them forever; others would take it forward.

We can see an example of that with Abraham Lincoln. In his Gettysburg Address in 1863, he talked about the “government of the people, by the people, for the people shall not perish from the earth”. Those words would make no sense without the Constitution being grounded on the idea that it was founded by “we the people”. Whatever we think of these fifty-five men, their words were later on used by Abraham Lincoln to bring about a “new birth of freedom”.

3.2 The Second Amendment

The Bill of Rights (1791)

Amendment I

Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.

Amendment II

A well regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed.

Amendment III

No Soldier shall, in time of peace be quartered in any house, without the consent of the Owner, nor in time of war, but in a manner to be prescribed by law.

I always have interesting discussions with students about the second amendment, which, to Europeans, seems the most alien thing in the American political system; it guarantees the right to have guns, in a country where there is no right to healthcare.

What does the 2nd amendment actually mean? Does it mean that everyone has the right to bear arms? Are there qualifications on the right to bear arms? Does it mean you have to be part of a “well-regulated militia”? The argument tends to fall depending on whether you want to end guns or not. I believe that these are enabling clauses, and that if we wanted to get rid of guns, the whole amendment would have to go or be changed.

There are two constitutional clauses about slavery: the three-fifths clause and the fugitive slave clause which meant that anyone running away from a state with slavery to a state without it had to be sent back.

3.3 Key abolitionist figures

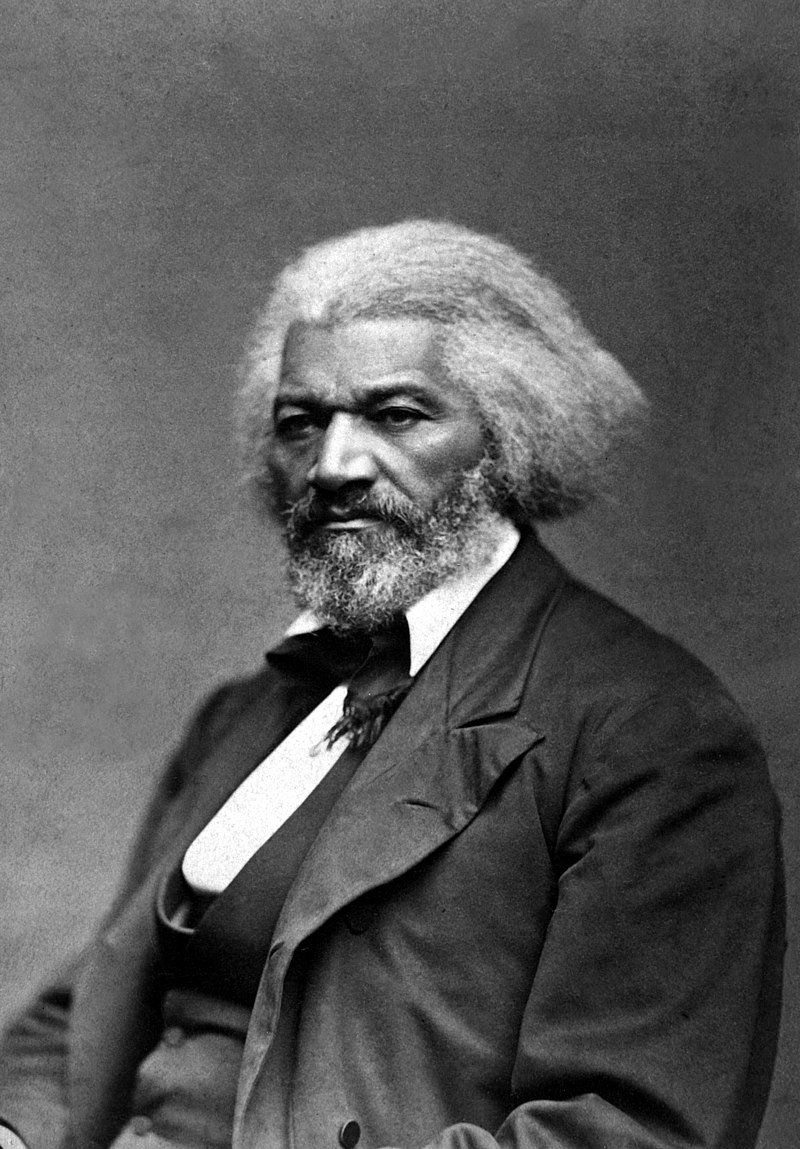

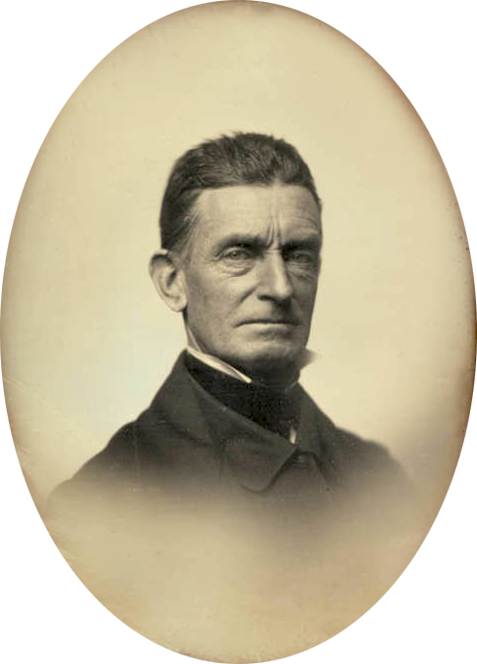

Obama regularly mentioned key abolitionist figures like William Lloyd Garrison, a radical abolitionist; Denmark Vesey, the slave rebel; Frederick Douglass, the abolitionist campaigner; Harriet Tubman, the Moses of the story, who not only escaped but went back to the slaves states thirteen times to guide others through the underground road; John Brown, the white abolitionist who tried to start a slave insurrection by trying to steal guns at Harpers Ferry in Virginia in 1858.

|

|

|

|

William Lloyd Garisson, 1870

Source: Wikimedia, Public Domain

|

Denmark Vesey (Charleston, SC)

Source: Wikimedia, CC BY-SA 4.0

|

Fredericak Douglass, circa 1879

Source: Wikimedia, Public Domain

|

|

|

|

Harriet Tubman by Horation Seymour Squyer, 1848

Source: Wikimedia, Public Domain

|

John Brown by Southworth & Hawes, 1856

Source: Wikimedia, Public Domain

|

We can study Frederick Douglass’s speech “The Meaning of July Fourth for the Negro”, as it is very Obamaian. He says explicitly that the values of the Declaration are hypocritical. Everyone focused on the hypocrisy of the 4th of July celebrations, on liberty, while there was still slavery. But he says: “stick to those of liberty, campaign for those values of liberty to eradicate slavery”. He did not lose faith in the ideals in spite of the reality of his time.

Obama also mentions “freedom songs”, such as Rivers, which represent the borders between the slave states and the free states. But slaves had to sing in codes, so they put it in Biblical terms.

Roll, Jordan, Roll

Went down the River Jordan,

Where John baptized three,

When I walked the Devil in Hell,

Said John ain’t baptized me,I said, roll, Jordan, roll,

Roll, Jordan, roll,

My soul ought to rise in heaven, Lord,

For the year when Jordan rolls,Well, some say John was a Baptist,

Some say John was a Jew,

Well, I say John was a preacher,

And my bible says so too,I said, roll, Jordan, roll,

Roll, Jordan, roll,

My soul ought to rise in heaven, Lord,

For the year when Jordan rolls, Hallelujah….

Pour citer cette ressource :

Steven Sarson, All men are created equal? Barack Obama and the American Revolution, La Clé des Langues [en ligne], Lyon, ENS de LYON/DGESCO (ISSN 2107-7029), mars 2019. Consulté le 17/11/2025. URL: https://cle.ens-lyon.fr/anglais/civilisation/domaine-americain/all-men-are-created-equal-barack-obama-and-the-american-revolution

Activer le mode zen

Activer le mode zen